“No Carriage from L. & if there was—no permiso. to pass”

On 22 Apr 1775, three days after the Battle of Lexington and Concord, the Boston merchant and magistrate Edmund Quincy sat down to write a letter to John Hancock.

On 22 Apr 1775, three days after the Battle of Lexington and Concord, the Boston merchant and magistrate Edmund Quincy sat down to write a letter to John Hancock.

Quincy wasn’t just a colleague of Hancock in the Boston Patriot movement. He was also the father of Dorothy Quincy, Hancock’s fiancée (shown here).

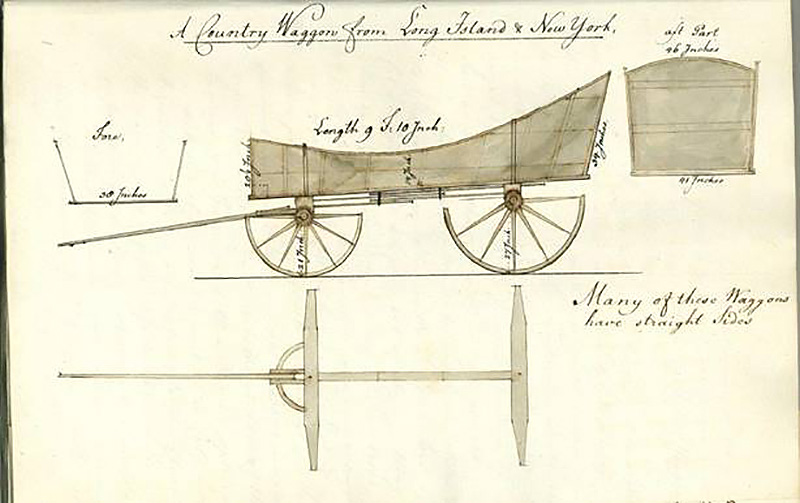

Earlier that month, Dorothy had taken the family carriage out to Lexington and then used it to flee with Lydia Hancock from the regulars on 19 April. That left her father stuck inside Boston as the siege began.

Justice Quincy wrote to Hancock:

Dear Sir,There are a lot of interesting bits of intelligence in this letter—Gen. Thomas Gage hoping to seize the heights of Dorchester, Col. Percy criticizing his Concord mission, Lt. Hawkshaw saying the British soldiers had fired first. Quincy urged Hancock and his colleagues to send the Patriot side of events to London as quickly as possible.

Referring you to a Ltr. wrote the 8th. currt: [i.e., of this month] I’m now to enclose you one I had this day out of [ship captain John] Callihan’s bag:—32 days fro. Lond: into Salem pr young Doct. [John] Sprague—who tells me [captain Nathaniel Byfield] Lyde sail’d 14 days before them wth. Jo. Quincy Esq & other passengers—that some of ye Men of War & transports sail’d also before Callihan. As to ye times [?] at home—ye Doctr. is little able to inform us—youl probably have Some papers via Salem.—————

As to my Scituation here ye unexpected extraordy. event of ye 19th: of wch. Ive wrote my thots—) now & for days past impedes my leaving town[.] No Carriage from L[exington]. & if there was—no permiso. to pass ye lines—The people will be distress’d for fresh provisions—in a Short time—

The Govr: & Genl.—is very much concern’d about ye Provl. troops without—wch. probably will be very numerous ’ere long if desired—Dorchester hill—I’m just now told, is possess’d by our provls—& I hope its true, for Ive reason to believe, ye Genl. had ye same thing in Contemplation——

Here they say & swear to it all round, in excuse of ye Regulars, proceeding at Lexinton—that they were attack’d first & I doubt not many oaths of Officers & men are taken before J. G—ley [Justice Benjamin Gridley], to confirm it—but among others who contradict ’em—Lt. [Thomas] Hawkshaw yesterday near expiring thro. his bad wounds——Call’d Several Credible persons to him & told ’em as a dying man—that he was obliged in Conscience to confess—that the first Action of ye Whole at L. was done by the Kings troops—wr. they killd & wounded eight men—but doubtless you have sufficient proof of ye Fact & every Circumstance attending near at hand—

my advice is that the Whole Matter—be forwarded at ye province expence or otherwise wth. the Greatest dispatch—that so your Advices may be in London as early as GG’s——

If the people of G:B: are not under a political Lethargy—The Account of ye late Memorable Event, will excite them to consider of their own Close Connexion wth. America; and to Suppose at length, that ye Americans especially N. Englanders will act as they’ve wrote, & engag’d—A Blessed Mistake our prudent G[ag]e has indeed made, & ye Sensible part of his Officers & Soldiers own it—& are vastly uneasie—

I had been at L— days to pay my real regards to yr. good Aunt & Dolly—but wn. we shall have ye passage clear I dont [know] we are in hopes of effecting soon. But ye Gl. is really intimidated & no wonder wn. he hears of 50.000 men &c.—Much is Confess’d of ye intripedity of ye provinls. Im much Surpriz’d to hear that the Regulars abt. 1700—were drove off & defeated by near an Equal Corps only.—

Capt. [John] Erving, at his house yesterday Gave me ye Account of Hawkshaws Confesso.-proved to him at ye No: End yesterday to be real, he also says that from all he can gather from ye Circumstances of the people of Gt. Bn. they are by this day in a State of fermentation—if we could be so happy, as to get speedily home, the necessary advices—I doubt not a Flame would soon appear—& ere its quench’d, may it burn up ye heads of the Accursed Faction fro. whence ye present British Evils spring

Genl. Gage is thrown himself into great perplexity—Ld. Percy is a thorn in his side & its said has menaced him Several times, for his late imprudence—a Good Omen

I cant nor ought I to add, but my best regards—& Love respectively & that I am

Dr. Sir Your most affecto: Friend

& H. Servt.

Ed. Quincy

youl excuse erro. for Ive not time to correct em

How did John Hancock respond to seeing this letter? In fact, he never saw it.

TOMORROW: Diverted mail.