“It was covertly agreed to use their concealed arms”

The Swifts’ grandson Joseph Gardner Swift inherited that idea, telling John Adams in 1824 that Samuel Swift “died in 1775 a Prisoner & Martyr under the Tyrrany of [Gen. Thomas] Gage.”

Over the course of the nineteenth century, that family tradition got into print and became more detailed and dramatic.

When Samuel and Ann Swift’s son, Dr. Foster Swift, died in 1835, the Army and Navy Chronicle’s obituary stated that the attorney had been “a distinguished Whig and martyr to the cause of Freedom while a prisoner in Boston, anno 1775.”

In the 1880s Harrison Ellery, who had married into the Swift family, assembled a genealogy that incorporated the family lore.

Ellery loaned his page proofs to local historian Albert Kendall Teele, so the first public version of the full tale of Samuel Swift, zealous Patriot, appeared in Teele’s History of Milton in 1887:

When General Gage offered the freedom of the town to Bostonians who would deposit their arms in the British Arsenal, Mr. Swift opposed the movement. He presided at a meeting where it was covertly agreed to use their concealed arms, also pitchforks and axes, to assail the soldiers on Boston Common.Oliver Ayer Roberts relied on that account in his collection of biographies of members of the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company. It contained some clear errors, such as the date of Samuel Swift’s death and the surname of his first wife.

This scheme was revealed to General Gage, and Mr. Swift was arrested, he was permitted to visit his family, then at Newton, upon his parole to return at a given time. At the appointed time he returned, against the remonstrance of his friends, and so high an opinion of his character was entertained by General Gage that he was permitted to occupy his own house under surveillance.

From disease induced by confinement, he died a prisoner in his own house, a martyr to freedom’s cause, Aug. 31, 1775. He was interred in his tomb, which had formerly belonged to the father of his first wife, Samuel Tyler, Esq.

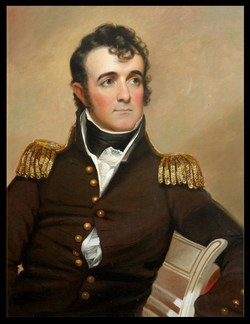

Ellery published his genealogy in 1890 as part of The Memoirs of Gen. Joseph Gardner Swift. In the introduction to that book Ellery wrote of seeing Joseph G. Swift’s “journal,” but the chapters that follow are a retrospective narrative in the general’s voice. I can’t tell if Gen. Swift actually wrote out a memoir and Ellery called it a journal, or if Ellery himself adapted a real journal into narrative form. Either way, that’s the source on Gen. Swift’s one meeting with John Adams that I quoted back here.

The genealogical section of that volume offered Ellery’s rendering of the Samuel Swift legend:

President John Adams told his distinguished grandson, General Swift, while on a visit to his seat in Quincy in 1817 with President [James] Monroe, that Samuel Swift was a good man and a generous lawyer, and was called the widows’ friend; that he was a firm Whig whose memory the State ought to perpetuate. The same sentiments Mr. Adams expressed in a letter to William Wirt, of Virginia.It’s certainly a dramatic picture, sixty-year-old lawyer Samuel Swift organizing an uprising against the British troops using guns, pitchforks, and axes. And the family’s stated source for that story was none other than President John Adams.

Mr. Adams also said it was owing to the zeal and resolution of Samuel Swift that caused many Bostonians to secrete their arms when Gov. Gage offered the town freedom if arms were brought in to the arsenal; and that Mr. Swift presided at a freemason’s meeting where it was covertly agreed to use the arms concealed, and, in addition, pitchforks and axes, if need be, to assail the soldiery on the common; which scheme was betrayed to Gage, causing the imprisonment of Swift and others.

This imprisonment brought on disease from which he never recovered, and he died August 30, 1775, aged 60 years, as President Adams said, “a martyr to freedom’s cause.” His remains were interred in the tomb in the stone chapel ground that had belonged to Samuel Tylly, Esq., the father of his first wife.

COMING UP: What’s wrong with this picture.