Gunshots in the Countryside

The only Henry Vassall I was able to find on the family tree at this time was a nineteen-year-old son of William Vassall, discussed yesterday.

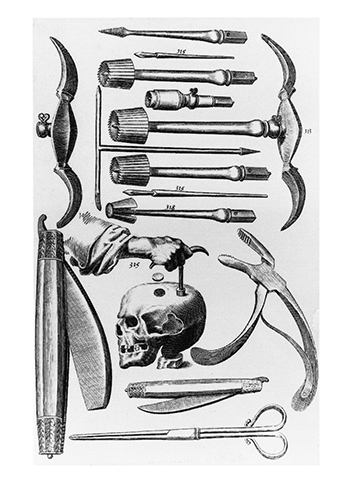

Henry was either visiting or staying with his cousin Elizabeth, wife of Dr. Charles Russell (1739–1780, shown here). I wonder if he was studying medicine.

Later that month Henry Vassall told the Charlestown committee of correspondence about his experience. He then wrote out an account for two Middlesex County magistrates, Henry Gardner of Stow and Dr. John Cuming of Concord:

Passing between the House of Mrs. Rebecca Barons [?] & Doct. Russell’s between the Hours of 7 & 9 in the Evening of the 7 instant [i.e., this month] & to the best of my Knowledge as I rose [?] a little Hill a little a past the first Canopy [?] I heard the report of a Gun saw the light and a Ball Enter’d the Carriage which I was in being Doct. Russells.Gardner and Cuming also gathered statements from a local man named Joseph Peirce and Luck, enslaved to Dr. Russell. Both declared that they had been traveling near young Vassall and had heard no gunshot.

I immediately step’d out of the Carriage & stood about five or six Minutes & then stepp’d into the Carriage Again & road in haste to the Doctor when I had gone a small Distance from the Place where the Gun was discharged I met a person on Horse back

when I had past a small Distance further I met several Persons riding on two Horses,

whether the Ball was aim’d at the Carriage I can’t say I further declare I do not know or even suspect who the Person was that Discharg’d the Gun as above mentioned . . .

NB. The above affair I declar’d to no person in Lincoln but the Revd. Mr. [William] Lawrence & desired him to keep it secret—Till the Friday Following.

Three members of the Lincoln committee of correspondence then wrote back to Charlestown agreeing that they detested “the Crime of Assassination” but casting doubt on Vassall’s complaint:

We shall only add that as the evening on which this event was said to have happened was very calm it is the general opinion here that it is very improbable if not utterly impossible that a gun should be Discharged at that time & place without being heard by many persons, you have Doubtless seen the impression in the Carriage & are able to judge & Declare whether it is the efect of a Bullet Discharged from a Gun or Not as well as any person in this townThis incident provided yet another reason for members of the Vassall family to seek safety surrounded by the king’s soldiers. (And on the same day that the magistrates wrapped up their investigation, people in Bristol, Rhode Island, threw stones at the chaise of Henry’s father and stepmother, William and Margaret Vassall. Newspapers reported that “next morning [they] set out for Boston.”)

This shot in Lincoln is only the second example I’ve found of someone in Massachusetts firing a gun at a supporter of the royal government. The first had occurred a couple of weeks earlier in Taunton.

According to Daniel Leonard, a veteran of the last war named Job Williams came to his house with a warning that “the People were to assemble” to protest how he had joined the mandamus Council. Leonard left, thinking that would head off the problem. Instead, on 22 August , or perhaps make it clear he wouldn’t be welcomed back. That crowd did arrive. Leonard wrote:

about five hundred persons assembled, many of them Freeholders and some of them Officers in the Militia, and formed themselves into a Battalion before my house; they had then no Fire-arms, but generally had clubs. . . .Back in 1769–1770, there had been three increasingly notorious incidents of government supporters shooting at crowds of protestors: the “Neck Riot,” Ebenezer Richardson killing Christopher Seider, and of course the Boston Massacre. But even in that period Massachusetts protestors had never shot at royal officials or their supporters.

My Family supposing all would remain quiet, went to bed at their usual hour; at 11 o’Clock in the evening a Party fixed upon the house with small arms and run off; how many they consisted of is uncertain, I suppose not many; four bullets and some Swan-shot entered the house at the windows, part in a lower room and part in the chamber above, where one Capt. Job Williams lodged. The balls that were fired into the lower room were in a direction to his bed, but were obstructed by the Chamber floor. . . . I conclude it possible that the attack upon the house was principally designed for him.

These untraceable gunshots in the late summer of 1774 show that some people in Massachusetts were starting to think it was acceptable to use that level of violence against Loyalists.