The 17 Aug 1770 issue of the

New Hampshire Gazette of Portsmouth included this announcement:

Last Week was Married in this Town, by the Rev. Dr. HAVEN, Mr. JOHN FLEMING, of Boston, Printer, to Miss. ALICE CHURCH, Daughter of Mr BENJAMIN CHURCH, of the same Place, Merchant,----an agreeable young Lady, adorn’d with the Qualifications requisite to render that honorable State happy.

Records of the Rev.

Samuel Haven’s meetinghouse specify that the couple were married on 8 August—

250 years ago today.

Boston newspapers reprinted that news in the following week, with the 21 August

Massachusetts Spy (cramped for space) leaving off the encomium to the bride but identifying her father as an “Auctioneer.”

Alice’s father, Benjamin Church, Sr., was indeed well known in Boston for his vendue-house. He wasn’t a native of the town but had been born in Bristol,

Rhode Island, in 1704. His father died when he was two, and he grew up mostly in the household of his paternal grandfather, also named

Benjamin Church, famous in New England for leading guerrilla war against

Native nations in the late 1600s.

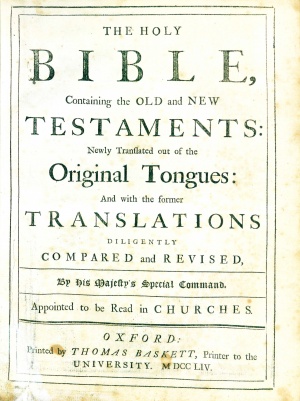

After graduating from

Harvard College in 1727, the younger Benjamin Church went into business in Newport. He married Elizabeth Viall that October, and they had two

children before she died in 1730. Church married again in 1732, to Hannah Dyer of Boston. He continued to develop his auction house in Newport.

Around 1740, Church moved his business and family to Boston. He owned various real estate, invested in the Land Bank, and established a new vendue-house in the South End. He specialized in selling cloth and other goods just off the ships. Church also served in public posts: as a minor town official and a deacon in the Rev.

Mather Byles’s Hollis Street Meetinghouse. He penned Latin poems and a biography of his grandfather.

Benjamin and Hannah Church had eight children.

Benjamin, Jr., was the first boy, born in 1734 and graduating from Harvard twenty years later. He became a

physician and, by the late 1760s, one of the leaders among Boston’s Whigs, known for his genteel manners and satirical verse. In March 1770 Dr. Church performed an autopsy on the body of

Crispus Attucks.

Alice Church was one of Benjamin and Hannah’s younger girls, baptized at the Hollis Street Meetinghouse in 1749. That meant she was around twenty-one years old when she married printer John Fleeming. He was older, but we don’t know by how much, only that he had been in business since arriving in Boston from Scotland in August 1764.

There are some mysterious aspects of this wedding. First, John Fleeming had been partner to

John Mein in printing the

Boston Chronicle. In that newspaper and subsequent political pamphlets, Mein sneered at Dr. Church the “Lean Apothecary.” Some have interpreted that to mean

Dr. Joseph Warren, but Mein’s own handwritten “Key” to the pamphlet (now in the Sparks Manuscripts at Harvard) states he meant Church and further described him as:

One of the greatest miscreants that walks on the face of the Earth who has cheated & back bitten every Person with whom he ever had the least Connection—Father Mother & friend & more than once foxed his Wife &c &c &c

So right away we can ask how John Fleeming and Alice Church ever became friendly.

The next big question is why did they get married in

New Hampshire. Massachusetts couples went over the border if they were eloping or needed to marry quickly because a baby was on the way. There’s no evidence to confirm either of those possibilities, but we know little about the Fleemings.

Church researcher

E. J. Witek noted a possible third factor. John Fleeming had taken refuge on

Castle Island at the end of June after shutting down the

Chronicle, so he might not have felt safe going to a church in Boston. Still, I think he could have found a minister closer to home than Portsmouth.

John Fleeming was connected to the

Sandemanian sect while Alice Church had been raised in the Congregationalist

faith. They were married by a Congregationalist minister. But the Fleemings had a daughter named Alicia baptized at

King’s Chapel, an Anglican church, on 17 July 1772 (and Dr. Benjamin Church was one of the baby’s sponsors). Again, questions but no answers.

The family link between John Fleeming and Dr. Benjamin Church became an issue of state in 1775 when Gen.

George Washington and his staff realized that Church had tried to send a ciphered letter into Boston via his mistress, Mary (Brown) Wenwood. Deciphered, that letter turned out to be to Fleeming. In his defense, Church turned over a letter he had received from his brother-in-law. It said things like:

Ally joins me in begging you to come to Boston. . . . your sister is unhappy under the apprehension of your being taken and hanged for a rebel . . . If you cannot pass the lines, you may come in Capt. [James] Wallace, via Rhode Island, and if you do not come immediately, write me in this character, and direct your letter to Major [Edward] Cane on his Majesty’s service, and deliver it to Capt. Wallace, and it will come safe. . . . Your sister has been for running away; Kitty has been very sick, we wished you to see her; she is now picking up. I remain your sincere friend and brother…

That reads like a genuine familial friendship even though the men were on opposite sides of the war. And the link was forged 250 years ago today.

(While researching the Church genealogy, I realized that Dr. Church’s older half-sister Martha was stepmother to the teen-aged assistant teacher at the South Writing

School in 1774,

Andrew Cunningham. Both Dr. Church and young Cunningham, his step-half-nephew, are players in

The Road to Concord, one helping to conceal the Boston

militia train’s stolen

cannon and the other helping Gen.

Thomas Gage hunt for them.)