The Last Years of Henry Howell Williams

Close relatives married members of the Crafts, Dawes, Heath, and May families, all prominent in republican Boston.

Though in 1787 he told Henry Knox that he’d been “reduced to beggary” by his losses in the spring of 1775, Williams actually appears to have maintained a genteel lifestyle.

By 1784, as I wrote back here, Williams was once again living on Noddle’s Island, employing enough laborers that they needed their own building. An 1801 survey of the island labeled his rebuilt home as a “Mansion House.”

Williams also had the resources to keep petitioning one level of government after another, cajoling supportive letters from various officials. In 1789, the state of Massachusetts granted him £2,000.

Four years later, Williams bought the Winnisimmet ferry from the family that had run that concession for decades. He upgraded it and made good money for a decade crossing the Mystic River.

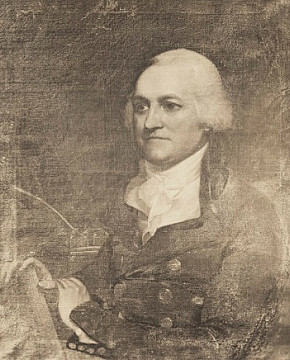

In 1797, Williams’s eldest daughter Elizabeth (1765–1843, shown here in a portrait by Gilbert Stuart) married Andrew Sigourney, who became the treasurer of Boston. His daughter Harriet married a son of John Avery, the state secretary. Other Williams siblings married another Sigourney, another Avery, and a couple of Williams cousins.

In that decade, Henry Howell Williams moved his family off of Noddle’s Island to mainland Chelsea. One of his last public acts, in January 1802, was to petition the state legislature to compensate him for the income he’d lose after a consortium built a bridge across the Mystic.

Williams didn’t live to see that bridge. He died in December 1802 after “three months confinement.” Lengthy death notices appeared in the Columbian Centinel and Massachusetts Mercury, obviously written by relatives and friends. They praised him as a generous host, a vigorous farmer, and a beloved family patriarch. (Notably, they make no mention of any service to the republic during the war.)

As I mentioned above, Williams’s daughter Harriet married John Avery’s son, John, Jr. In 1800, the next year, they had a son, also named John. And then in October those parents were lost at sea. Little John was raised by relatives, perhaps maiden aunts. He wouldn’t have remembered his grandfather, but he would have grown up on stories about him.

In particular, young John probably heard about the building on the Noddle’s Island farm that had once been a barrack for the Continental Army in Cambridge, and about how his grandfather’s livestock had gone to feed those troops. Putting those facts together in the most complimentary way probably gave rise to what Avery told William H. Sumner later in life: that his grandfather had been some sort of quartermaster supplying the army, and that the barrack had been a reward from the Continental commander, George Washington himself. Contemporaneous records tell a different story.

The third John Avery showed Sumner the file of documents his grandfather had collected to make his case for compensation. In 1911 another heir, Henry Howell Williams Sigourney, donated those papers to the Massachusetts Historical Society. They’re what got me started on this series about one long-extended outcome of the Battle of Chelsea Creek.