“The Judge supposes he is possessed of the secret”

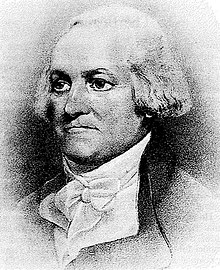

In January 1773, the Massachusetts judge Peter Oliver went to Rhode Island to serve on the royal commission investigating the attack on H.M.S. Gaspée.

Politically the Rev. Ezra Stiles was opposed to Oliver and the inquiry, but he was still polite enough to host the man.

On 11 January, Stiles wrote in his diary:

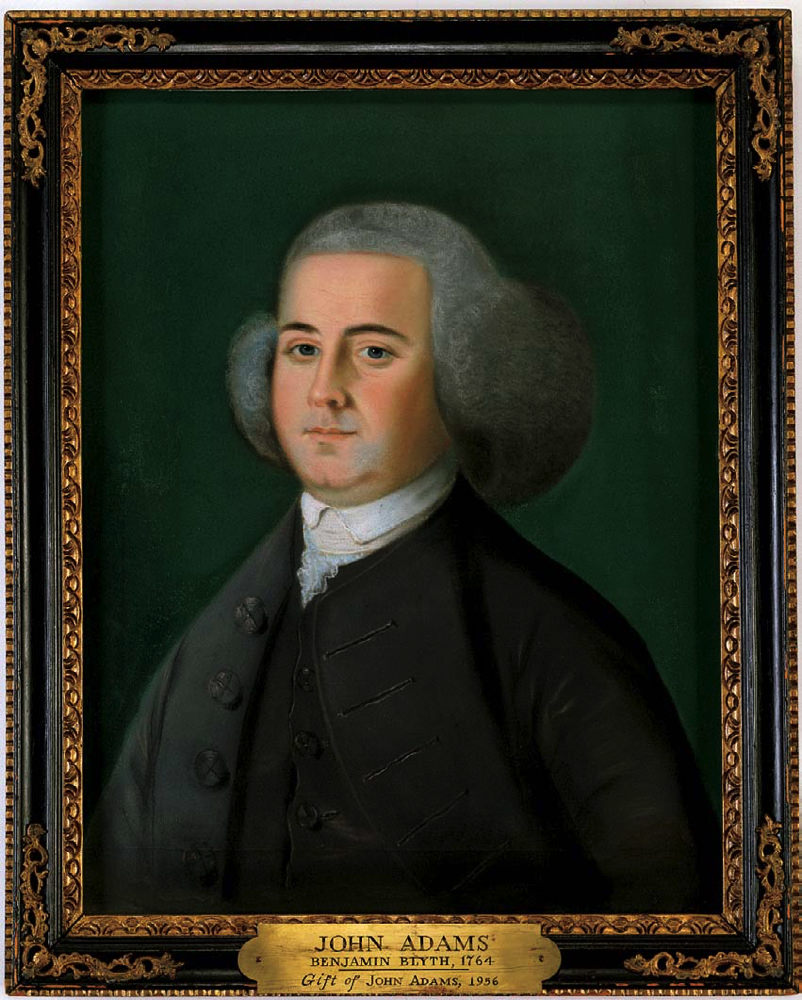

This Afternoon the hon. Judge Oliver came to drink Tea with me and spent the Evening at my house in Company with Mr. [Robert?] Stevens, Major [Jonathan] Otis and Dr. Jabez Bowen of Providence.Peter and Mary (Clarke) Oliver’s son Peter (1741–c. 1831) was a respectable sort of doctor: upper-class, male, practicing standard medicine for his time. Nonetheless, Mary sought treatment from John Pope.

The Judge told us that his Wife had been last year cured of a Cancer in her Neck of 30 years standg. by a young man Mr. [John] Pope of Boston. . . .

His remedy is a secret, but he explained the operation of it to Mr. Oliver in a philosophical Manner, though Mr. Pope is not a man of Letters nor does he make pretension to any other part of Medicine or Surgery.

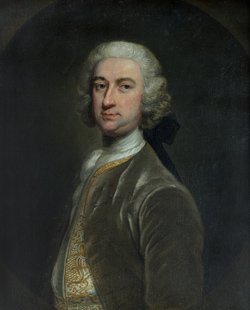

How good that treatment was over the long term is another question. Mary Oliver died on 24 Mar 1775 at the age of sixty-one. Among the pictures of Judge Oliver is one, reproduced above, showing the man mourning at his wife’s grave. It’s one of the rare portraits from the time of a person displaying strong emotion.

Stiles wrote down some of Oliver’s other medical remarks in 1773:

The Judge said that the late Mr. Little of Plymouth found an absolute Remedy for the Quincy, called white Drops, and offered me the Receipt. I suppose it the same as Dr. Bartlets which is only volatile Sp[iri]ts. as Hartshorn or Salarmoniac mixed with Oyl Olive. . . .The most common name for those flowers today is wild iris.

The Judge knew an illiterate physician to cure his (the Judge’s) Negro of a bilious Colic or perhaps the Illiac passion in a few Minutes—but would not disclose his Remedy. But the Judge supposes he is possessed of the secret, though that physician died without communicating it even to his own son. For being on the Circuit of the Superior Court in the Co. of York he found a Countryman to the Eastward [i.e., in Maine] who had a Cure for the bilious Colic, which Dr. Lyman had proved infallible in 100 instances.

The Judge bought it of the Man for 30. and it was only the Root of Meadow Flags, or Flower de Luce. Not every flag—but such only whose Root was flat with prongs—that flag root which was surrounded with bushy Fibres will not answer.