“Ye most vilolent Fire Perhaps yt Ever was heard of in this Country”

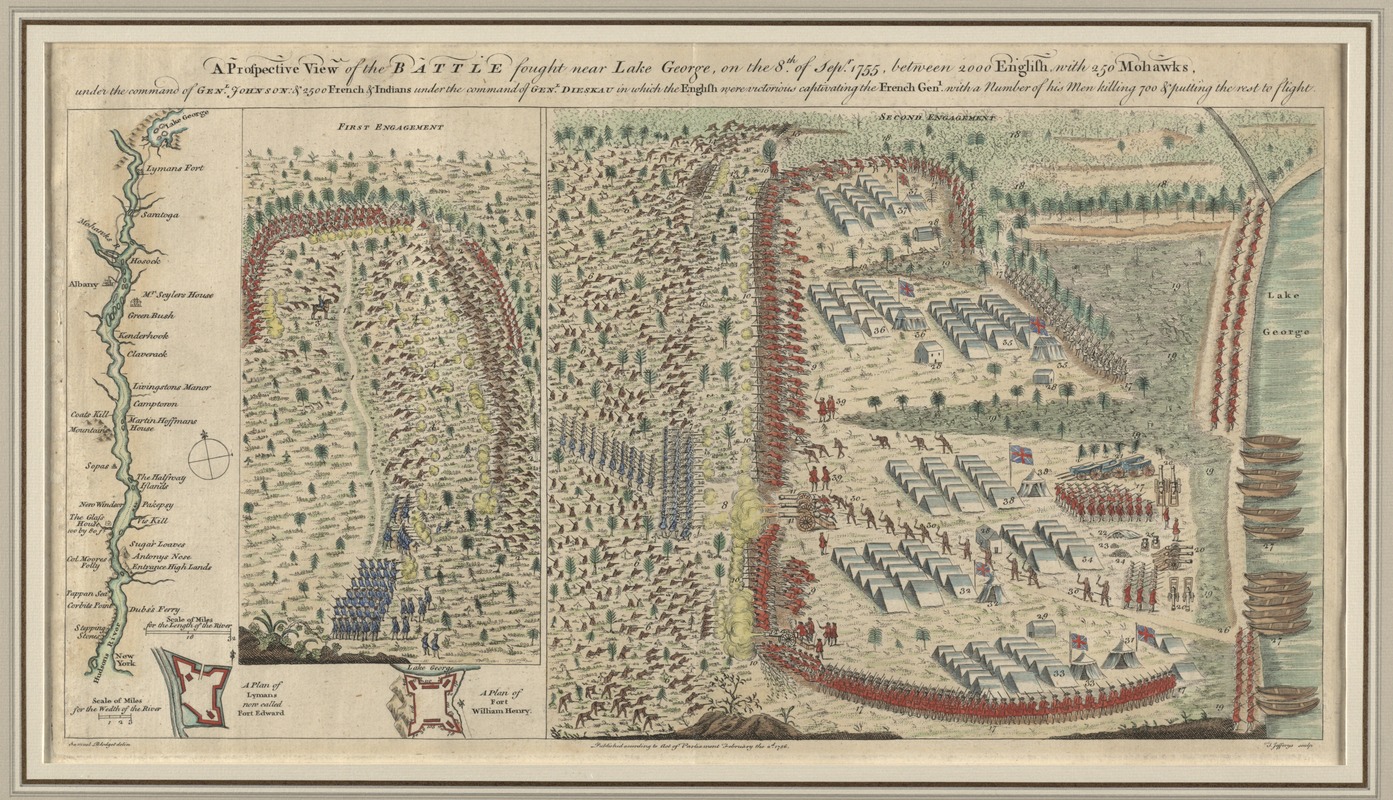

Yesterday we left Capt. Nathaniel Folsom of New Hampshire and Capt. William Maginnis of New York leading their provincial companies north from Fort Lyman (soon renamed Fort Edward) on the afternoon of 8 Sept 1755. They were headed to Gen. William Johnson’s camp at Lake George, a distance of at least fifteen miles.

That morning, French forces had successfully ambushed a British column that had tried to come the other way. The column’s commanders were killed, leaving Lt. Col. Nathan Whiting of Connecticut and Lt. Col. Seth Pomeroy of Massachusetts in charge.

Pomeroy’s diary, published by the Society of Colonial Wars in New York in 1926, offers a vivid description of what happened:

Meanwhile, Folsom and Maginnis were moving north. According to Folsom’s March 1756 letter to the Rev. Samuel Langdon, published by the Massachusetts Historical Society in 1904, Capt. Maginnis neglected to send out “advance guards” to prevent an ambush and moved too slow besides.

(Maginnis might have countered that for all of Folsom’s claim that he and his officers were hungry to enter the fight, they’d managed to beat the Yorkers back to Fort Lyman and then lagged them in returning to face the enemy.)

Toward the late afternoon:

TOMORROW: Endgame.

That morning, French forces had successfully ambushed a British column that had tried to come the other way. The column’s commanders were killed, leaving Lt. Col. Nathan Whiting of Connecticut and Lt. Col. Seth Pomeroy of Massachusetts in charge.

Pomeroy’s diary, published by the Society of Colonial Wars in New York in 1926, offers a vivid description of what happened:

we this Morning Sent out about 1200 men near 200 of them our Indians went Down ye Rhode toward ye Carrying pla[ce] got about 3 miles they ware ambush’d & Fir’d upon By ye Franch and Indians a number of ours yt war Forward Return’d ye Fre & fought bravely but many of our men toward hind Part FledThat general was Jean-Ardman, Baron Dieskau. He’d been shot four times and declared that the last wound was mortal. But in fact he survived as a prisoner of war in Britain until 1763 and then at home another four years.

ye others being over match’t ware oblig’d to fight upon a Retreet & a very hansom retreet they made by Continuing there fire & then retreeting a little & then rise and give them a brisk Fire So Continued till they Came within about 3/4 of a mile of our Camp

there was ye Last Fire our men gave our Enenies which kill’d grate numbers of them Sean to Drop as Pigons yt put ye Ennemy to a Little Stop

they very Soon Drove on with udanted Corage Doun to our Camp

ye Regulars Came rank & File about 6 abrest So reach’d near 20 rods In Length Close order the Canadans & Indians Took ye Left wing Hilter Scilter down along Toward the Camp

they had ye advantage of the ground Passing over a hollow & rising a note within gun Shot then took Trees & Logs & Places to hide them Selves-we made ye best Shift we Could for battrys to get behind but had but a few minuts to do It in

Soon they all Came within Shot ye regulars rank & file they Came towards yt Part of ye Camp whare we had Drew 3 or 4 Field Peaces ye others towards the west Part of ye Camp there I Placed my Self Part of Coll. [Timothy] Ruggles & of our Rigement a long togater

the Fire begun between 11 & 12 of ye Clock and Continued till near 5 afternoon ye most vilolent Fire Perhaps yt Ever was heard of in this Country In any Battle then we beat ’em of ye ground

we Took ye French General wounded

Meanwhile, Folsom and Maginnis were moving north. According to Folsom’s March 1756 letter to the Rev. Samuel Langdon, published by the Massachusetts Historical Society in 1904, Capt. Maginnis neglected to send out “advance guards” to prevent an ambush and moved too slow besides.

(Maginnis might have countered that for all of Folsom’s claim that he and his officers were hungry to enter the fight, they’d managed to beat the Yorkers back to Fort Lyman and then lagged them in returning to face the enemy.)

Toward the late afternoon:

Captain McGennes and company started nine Indians, who run up the wagon road from us, upon which Captain McGennes stopt. I, seeing them halt (being on a plain) ordered our men to move forward and pass by them. As soon as I came up with McGennes, I asked the reason of his stopping, which he told me was the starting of the Indians.Folsom said his force consisted of “but 143 men”—leaving out the 90 Yorkers, of course.

I then moved forward and we ran about 80 rods and discovered a Frenchman running from us on the left. Some of us chased him about a gunshot, fired at him, but, fearing ambushments, we turned into the wagon road again and traveled a few rods, when we discovered a number of French and Indians about two or three gunshots from us.

Then we made a loud huzza and followed them up a rising ground and then met a large body of French and Indians, on whom we discharged our guns briskly, till we had exchanged shots about four or five times.

When I was called upon to bring up the Yorkers, who I thought had been up with us before but finding them two or three gunshots back, I ordered them up to our assistance. And though but a small number of them came up, we still continued the engagement and soon caught a French lieutenant and an Indian, who informed us that we had engaged upward of 800.

TOMORROW: Endgame.