As I

noted yesterday, earlier this year Mayor Thomas Koch of

Quincy raised the idea of moving

John Adams’s books from the

Boston Public Library, where they’ve been for a century and a quarter, to his city.

That was part of an ambitious speech as Koch began his sixth term. At the time, of course, there was no pandemic in the U.S. of A. killing a thousand people a day, squelching tourism, slowing the economy, and taking a big bite out of municipal budgets. That situation has pushed a lot of big plans out further into the future.

Nonetheless, this month, as the

Patriot-Ledger reported on 14 August, Koch took the first step in trying to claim the John Adams library:

The city has formally requested that the John Adams book collection be brought back to Quincy in a letter to the Boston Public Library, which has kept and maintained the 3,000 volumes for more than 120 years. Mayor Thomas Koch says he wants the artifacts returned to Quincy, the president’s final resting place, and ultimately used as the focal point for a presidential library.

“My objective is to return this treasure of our local and our national history to the citizens of Quincy and dedicate a presidential library of sorts to John Adams and feature his collection as its centerpiece, among other important displays of our history,” the mayor’s letter, addressed to BPL President David Leonard, said. “I fully recognize the importance of this undertaking and am willing to commit the necessary resources to see the proper care of the collection as well as prepare a suitable home for it.”

Mayor Koch’s request is based on the idea that that the Adams books were merely loaned to the Boston Public Library in the 1890s. I don’t see such language in the publications of the time. Indeed, as I

wrote on Friday, while the Adams Temple and School Fund still referred to the books as the property of Quincy, the press of the time referred to the transfer of those books to the Boston Public Library as a “gift.”

The Adams Temple and School Fund lasted into this century with its last beneficiary being the

Woodward School, founded just about the time the Adams books went to Boston. A few years ago, that

school sued the city of Quincy for not exercising more fiduciary care over the fund. I don’t claim to understand the ramifications of the court’s decisions, but that case might have brought new attention to John Adams’s 1822 deeds to the city.

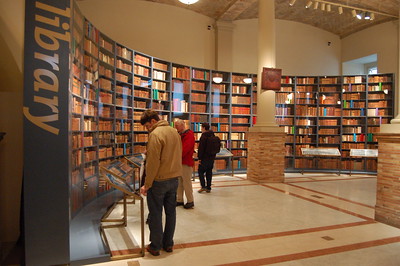

Mayor Koch now proposes to house the books in the Adams Academy building. That was the former

President’s original vision, but the books have never actually been there. By the time that academy opened fifty years later, people appear to have thought better of housing thousands of antique books and hundreds of

teen-aged boys in the same space. That building is now home to the

Quincy Historical Society, so it is a center of local heritage.

Koch’s proposal makes clear that he envisions the “John Adams Presidential Library” as a historical display for the public. As another example of such city projects, Koch “pointed to the $32 million Hancock-Adams Common, the park in front of city hall, as a preservation investment that current and future residents and visitors will enjoy.” The statue of John Adams in that park appears above.

When WBUR radio covered this story,

it reported: “The country’s second president granted his books and papers to the people of Quincy in a deed in the 1820s.” That’s only partly true. John Adams’s deed covered his books, not his papers. The family retained his documents, and eventually the Adams Manuscript Trust donated them to the

Massachusetts Historical Society. The city of Quincy has no claim on those papers.

And that brings up a major problem with this proposal for a “John Adams Presidential Library.” Presidential libraries are usually the repositories of Presidents’ papers and are always supposed to be places to study their lives and administrations. Simply having John Adams’s books would not create a Presidential library as scholars understand the term. The mayor’s comments on the project show no sign that it would be designed for researchers, not just tourists and local students on field trips.

Indeed, the mayor’s remarks to the press suggest that the driver of this proposal is to affirm local pride, to show that Quincy can boast the same historical resources as Boston. Of course, Quincy is already home to

Adams National Historical Park, with the houses of two Presidents and the book collection of one—but that’s a federal facility. A “John Adams Presidential Library” would be the city’s own shrine to one of its august citizens.

On Twitter, former Adams Editorial Project staffer Christopher F. Minty (now managing the

John Dickinson Writings Project) reacted to these developments about John Adams by quoting from a letter of Thomas Boylston Adams IV in 1962 when Massachusetts was considering a monument to the former Presidents. “I think it would be a pure waste of money to put up a statue or similar memorial,” that descendant stated; “The only memorial which I consider suitable to them is their writings.”

For people studying those writings, John Adams’s papers and John Adams’s books are now housed in major research libraries about half a mile apart on Boylston Street. I think the Boston Public Library’s Rare Books and Manuscripts department could use more funding, but it offers a full scholarly infrastructure. Back in 1893, the Adams Temple and School Fund said the books should go to Boston because more scholars would visit them at a bigger library in a bigger city. I think that’s still true.

_(14589850580).jpg/320px-By_trolley_through_eastern_New_England_(1904)_(14589850580).jpg)