I’ve been analyzing the likely sources for the 15 Jan 1776 article in

John Dunlap’s

Pennsylvania Packet about the

flag on Prospect Hill and other information from

Cambridge.

It’s clear one source was muster-master general

Stephen Moylan’s letter to

Joseph Reed, dated 2–3 January. Another was Gen.

George Washington’s letter to Reed on 4 January. But the article contained some details not from either of those documents.

One possibility is that Reed received yet another letter from his Cambridge contacts dated 3 or 4 January which he added to the mix. But Reed and his family appear to have been conscientious about preserving his papers, and no such letter survives. I think the key to that mystery lies in Joseph Reed himself.

Reed was a leading Philadelphia

lawyer before the war, with top contacts in London. He was also one of the city’s active Whigs, though not a member of the

Continental Congress.

When the Congress commissioned Washington as its generalissimo, Reed decided to accompany the Virginian on the first leg of his journey north. Then on the second leg. Then all the way to Cambridge to help set up a headquarters.

At each of these stages, Reed wrote back to his wife,

Esther, saying he’d be home soon. And then finally he had to break the news that Washington had convinced him to stay on as military secretary.

Reed worked alongside Washington in Cambridge from early July to late October. He drafted the general’s most important official correspondence, took notes on the top councils, and managed such initiatives as launching armed schooners against British supply ships. As part of the last task, Reed established

Connecticut’s “Appeal to Heaven” banner as the flag those schooners should fly in battle.

In November Reed returned to his wife and young

children. But he kept up a busy correspondence with the commander-in-chief and with other aides and officers he knew in Cambridge. The general hoped Reed would return as his secretary, so he didn’t give

Robert Hanson Harrison that job on a permanent basis until 16 May 1776.

In the winter of 1775–76, Reed continued to serve Washington, unofficially. He was the general’s ears in Philadelphia; “you cannot render a more acceptable service, nor in my estimation give me a more convincing proof of your Friendship,” Washington wrote, “than by a free, open, & undisguised account of every matter relative to myself.”

Reed promoted Washington’s interests in the Philadelphia press. As one example of this work, the general sent a copy of the laudatory poem that

Phillis Wheatley had written for him. After the British

evacuated Boston, those lines appeared in the

Pennsylvania Magazine. Reed probably spoke up for the commander in private conversations among politicians as well.

Even more important (and unusual) for Washington, Reed became an epistolary confidant. The general’s letters to his late secretary were more personal, emotional, even confessional than to almost any other colleague. Washington wrote about his frustrations, doubts, and personal wishes. Those letters said things that the general never expressed so bluntly to the Congress or never would have wanted to be public.

As for Reed’s side of that correspondence? We don’t know. In the dark days of late 1776, Washington opened a letter from Reed, who by then had been lured back into the military establishment as adjutant-general, to Gen.

Charles Lee, thinking it might have vital military information. That letter revealed that Reed and Lee had been criticizing Washington behind his back. After that, the commander-in-chief was never so friendly with Reed, or practically anyone else. And Reed’s side of their personal correspondence in late 1775 and early 1776 disappeared.

Thus, we have Washington’s 4 January letter to Reed, as saved by Reed and his heirs, but we don’t have the 23 Dec 1775 letter from Reed that Washington was responding to, or any of Reed’s following responses.

In the absence of those documents, I’ll proffer three speculations about what Reed wrote.

First, the details about the

Continental troops being “all in barracks, in good health and spirits,” and “impatient for an opportunity of action” came from Reed himself. They were what he as a Patriot politician wanted the people of Philadelphia to think. He certainly wasn’t going to publicize Washington’s actual gloomy assessment of the situation.

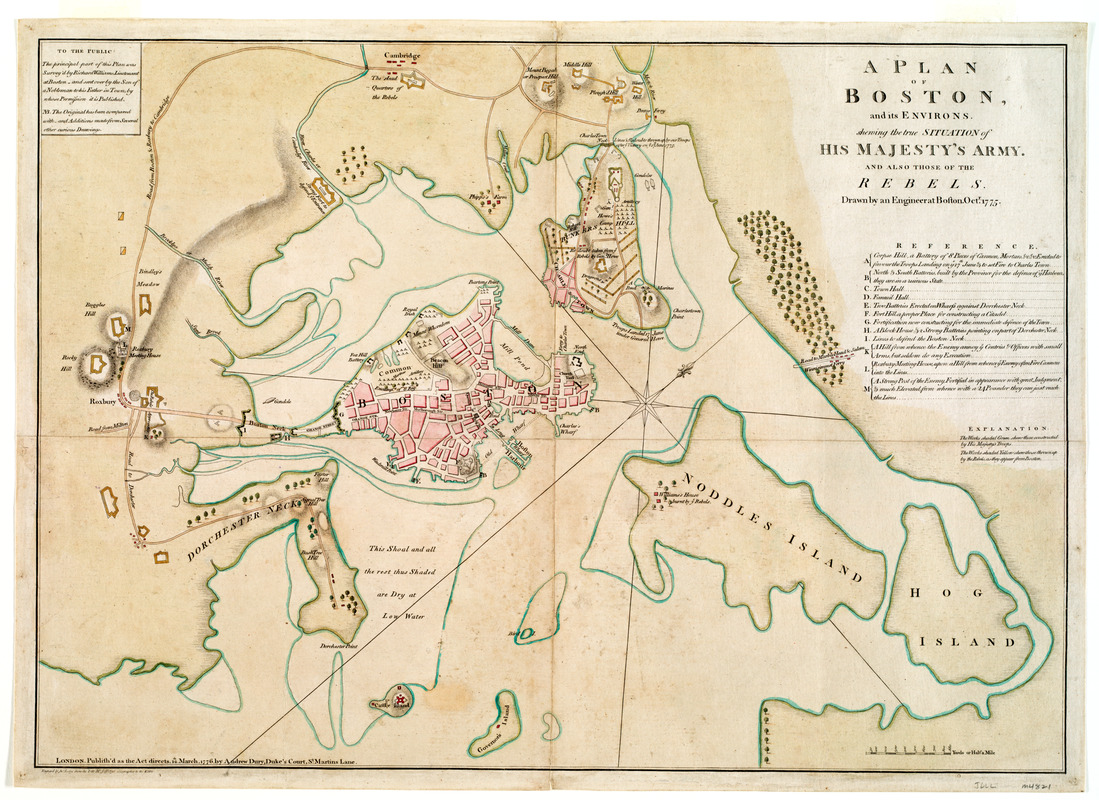

Second, the details about how the British had delivered copies of

the king’s speech to the Continental lines in

Roxbury and how the Continentals had raised their new flag on Prospect Hill before that speech reached Washington’s headquarters also came from Reed. Because he had worked in Cambridge for months, Reed knew how the two warring armies communicated. He knew where the big flagpole along the American lines stood. He could read Washington’s anecdote and fill in the blanks about how and where events unfolded.

Lastly, the new Continental flag that article referred to probably also came from Reed. I posit that he had sent a large version of the Congress’s new naval banner up to Cambridge, knowing there was a flagpole at Prospect Hill. Reed did that as Washington’s liaison in Philadelphia, and because he was concerned about naval banners.

Washington in turn sent back his anecdote about that flag, knowing his former secretary would be interested. And because Reed knew the size of that standard, his account for the

Pennsylvania Packet referred to it as “the great Union Flag.” It was a form of Union Flag, not only adapted with the Congress’s thirteen stripes but also notably big.

As I said, those are all speculations. It’s possible that letters from Reed or others will come to light showing I’m all wrong. But I think these suggestions fit the evidence we have now.

TOMORROW:

Another mystery in the flag anecdote.