Yesterday I quoted a description of the Rev.

Jonathan Homer of

Newton late in life, by the poet and doctor Oliver Wendell Holmes.

Homer’s writings include a “Description and History of Newton, in the County of Middlesex,” published in the

Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society in 1798. And

that article includes an anecdote related to the

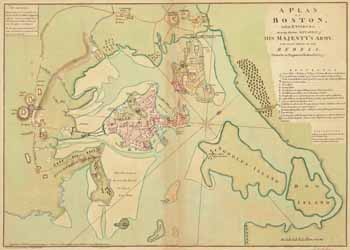

British army expedition to

Concord 250 years ago next month.

In writing about the local politician Abraham Fuller (1720–1794), Homer said:

To him, as principal of a committee of the Provincial Congress at Concord, were committed the papers containing the exact records of the military stores in Massachusetts at the beginning of 1775. Upon the recess of the Congress, he first lodged these papers in a cabinet of the room which the committee occupied.

But thinking afterwards, that the British troops might attempt to seize Concord in the absence of the Congress, and that these papers, discovering the public deficiency in every article of military apparatus, might fall into their hands, he withdrew them, and brought them to his house at Newton.

That foresight and judgment, for which he was ever distinguished, and which he displayed in the present instance, was extremely fortunate for the country. The cabinet was broken open by a British officer on the day of the entrance of the troops into Concord, April 19, 1775, and great disappointment expressed at missing its expected contents.

Had they fallen into their hands, it was his opinion, that the knowledge of the public deficiency might have encouraged the enemy, at this early period, to have made such a use of their military force, as could not have been resisted by the small stock of powder and other articles of war which the province then contained. He considered the impulse upon his mind to secure these papers, as one among many providential interpositions for the support of the American cause.

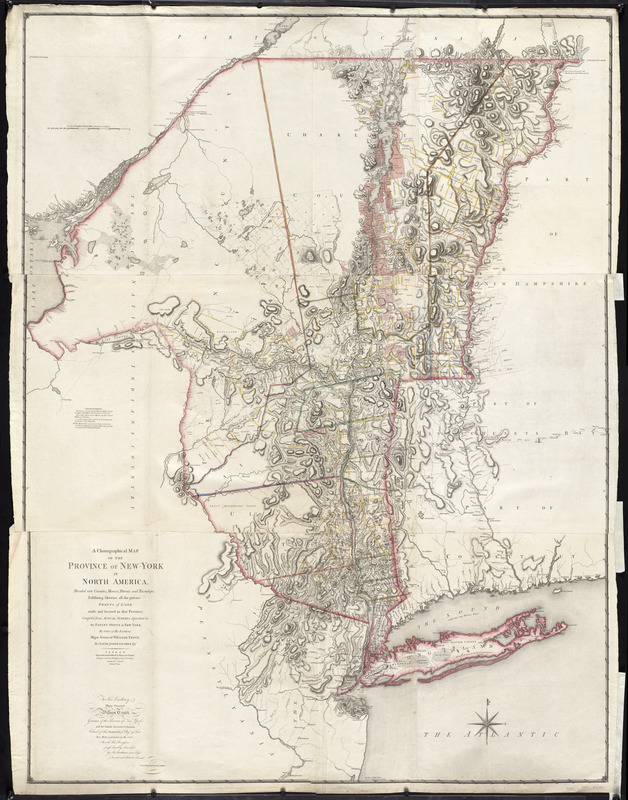

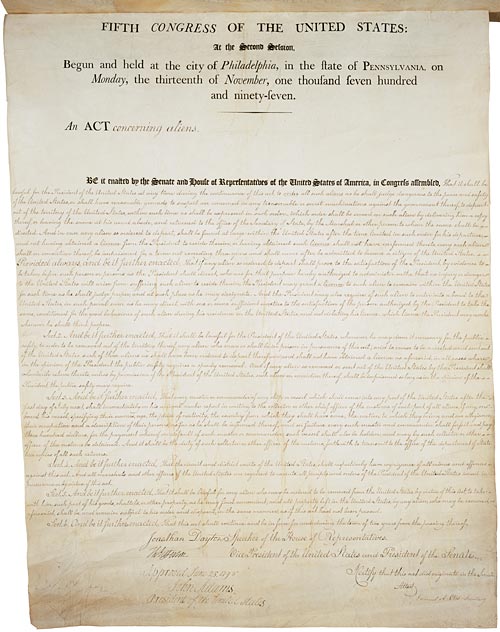

Fuller was indeed a member of a Massachusetts Provincial Congress committee appointed on 22 Mar 1775 “to receive the returns of the several officers of

militia, of their numbers and equipments,” plus inventories of the towns’ “stock of

ammunition.”

He wasn’t the senior member, named first and thus by tradition the chair. All the others—

Timothy Danielson of

Brimfield;

Joseph Henshaw of

Leicester,

Spencer, and

Paxton; James Prescott of

Groton; and

Michael Farley of

Ipswich—were colonels in the Massachusetts militia while Fuller was still a major. But he lived the closest to Concord, so it makes sense he felt responsible for securing the committee’s sensitive records.

(I should note that at this time, the congress included both Abraham Fuller from Newton and Archelaus Fuller from

Middleton, and that spring both men held the militia rank of major. Sometimes clerk

Benjamin Lincoln remembered to identify which “Major Fuller” the congress meant, and sometimes not. In this case, the official record dovetails with Homer’s story.)

Another version of this anecdote appears in the family genealogy

Records of Some of the Descendants of John Fuller, Newton, 1644–1698, published in 1869 by Samuel C. Clarke:

Judge Fuller was a very earnest patriot before the Revolution, and it is told that previous to the fight at Concord, fearing that the British might destroy the County Records at that place, he rode over from Newton the day before the fight, and carried away the most valuable of the papers in his saddlebags to his house in Newton.

Interestingly, in a footnote Clarke quoted Homer’s text, which says Fuller hid sensitive records for the whole province, making his action more important. Yet Clarke stuck to what seems to be the family’s idea that those were only “County Records.” In a way they were, since the militia regiments were organized at the county level.

Clarke’s version also said that Fuller wanted to prevent the British regulars from destroying those records rather then to prevent those soldiers from reading them. That seems more in keeping with the Patriot mindset in early April 1775. They thought they were preparing well for war, not woefully deficient, and feared the army might destroy their means of self-governance.

All that said, I’ve never come across evidence that the British troops in Concord were looking for Provincial Congress records. Gen.

Thomas Gage didn’t gather any intelligence about where those documents were kept or put them on his list of what the regulars should look for. No British officers on the march described such a search.

I therefore think that everything Homer wrote about “a British officer” breaking into the cabinet because he “expected” to find records inside is probably imaginary.

Fuller took care to keep those papers away from the army, just as

Paul Revere and

John Lowell took care to move

John Hancock’s trunk into the woods at

Lexington, and just as

Azor Orne,

Elbridge Gerry, and

Jeremiah Lee took care to hide from the troops passing by their tavern in

west Cambridge. But that doesn’t mean those careful actions thwarted the British mission in any way. We like to think our actions have an effect on the world.

(The photo above,

courtesy of Find a Grave, shows the Fuller family tomb in Newton’s east burying-ground. It’s about half a mile from my house.)

.jpeg)