“Recapturing the realities of daily governance”

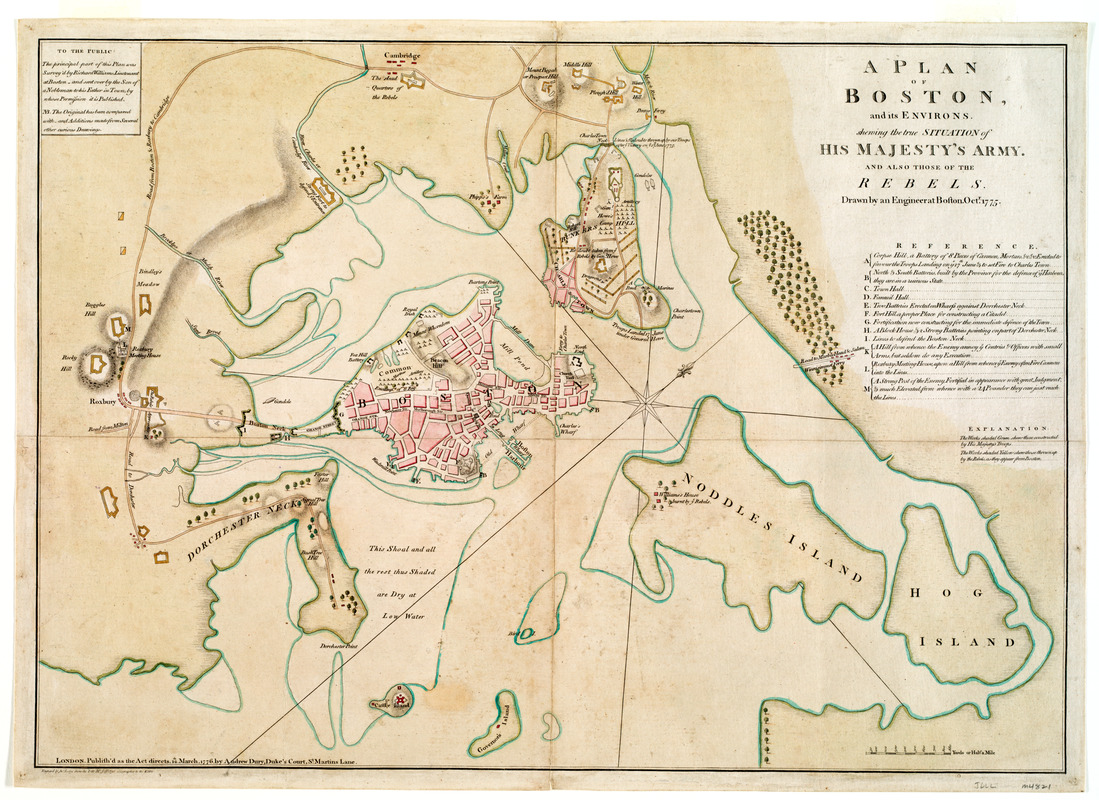

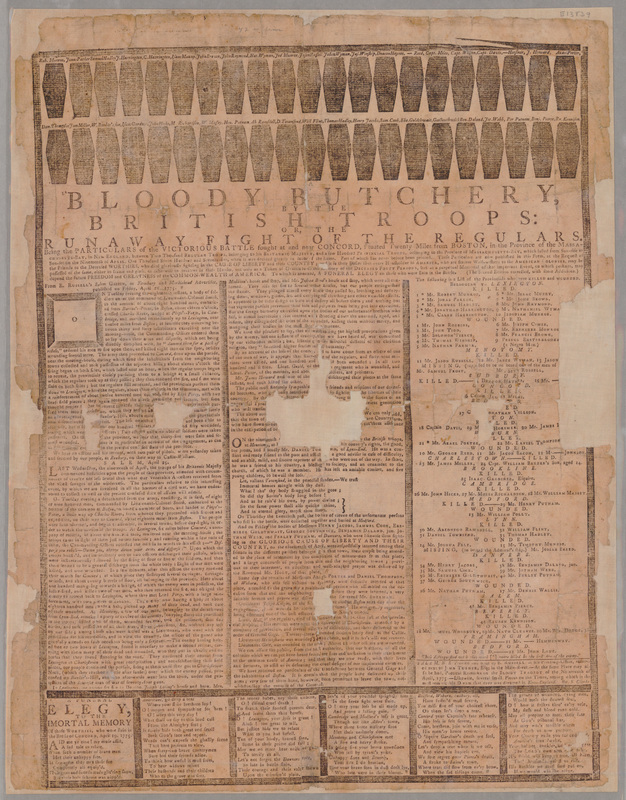

It seeks to document the U.S. federal government from its creation in 1789 until 1829. That starts with listing all the people documented as hired by the federal government in that period, their jobs, where they worked, and other details.

The project explains itself this way:

What happens to our story of the American founding when we shift the focus from the pursuit of electoral office and toward the actions of appointed officials? Recapturing the realities of daily governance is crucial to our understanding of both the nation’s past and its present. . . .Indeed, those high officials were flooded with requests from people seeking appointments. There was no civil service system to channel that process, simply personal connections and peristence.

Day in and day out, the Founding Fathers were consumed with managing the thousands of employees in the federal government. Much as we might now prefer reading their most high-minded writings about the meaning of representative government, once the Founders moved into federal leadership they were far more concerned with day-to-day matters. This does not mean they lost sight of the big picture or pressing national goals. Rather, they understood that their ability to realize their goals for the nation depended on their ability to organize and mobilize the personnel and resources of the federal government.

This task was all the more difficult because they did not possess the organizational tools that we have today. First and foremost, the federal government was highly decentralized. Although each federal agency did possess a central office in the nation’s capital, they had the most limited staff. Nothing reveals this state of affairs more clearly than the fact that so much of the minutiae of managing the federal government appears in the familiar handwriting of people like George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison. As cabinet members and later as Presidents, they devoted much of their time to appointing subordinates and drafting specific instructions to them.

Fortunately for those top managers, and for the people trying to document every federal employee, the national government was quite small. And for a brief time under one President, it got smaller:

That President was Thomas Jefferson, and the period was 1801-1803. Jefferson came into office convinced that the federal government had become too large and expensive. He also suspected that many in the federal workforce shared dangerous ideas that put them at risk of violating the commitment to republican government that was at the core of the government’s mission. So Jefferson fired a number of personnel and eliminated a small number of federal offices. The result was to produce a brief reduction in the total number of federal employees. But the combination of the Louisiana Purchase (which expanded the federal domain), international tension, and ongoing domestic challenges led Jefferson to hire new officials and create new offices. As a result, he left office with a federal government larger and more powerful than the one he inherited.In the period covered by this database, the population of the U.S. of A. grew from a little less than 4 million people to more than 12 million. Both the country and the economy expanded. So we shouldn’t be surprised that the federal government grew as well.

In contrast, for the last four decades the number of federal government civilian employees has hovered around 3 million (as high as 3.19 million in 1990, as low as 2.71 million in 2007). During that time, the national population has grown by more than 100 million people, or 46%.

TOMORROW: Looking in the Creating a Federal Government database for familiar faces.