The Good Properties of Richard Lechmere

Charles Bahne, Cambridge historian and good friend of the blog, commented:

I question whether Richard Lechmere ever lived in what is now called East Cambridge. Certainly he owned a lot of land there, much of it inherited from his in-laws, the Phips family, and then he bought more parcels from other Phips heirs. And from this we get the names of Lechmere's Point, Lechmere Square, Lechmere station, and, at one time, the Lechmere Sales chain of department stores.There’s no dispute that Richard Lechmere owned a lot of property when he left Massachusetts. On 13 Oct 1784 he applied to the Loyalists Commission, seeking compensation for his losses. The commission’s records discuss “his House in Boston,” “his farm at Cambridge,” part of “a great Distillery at Boston,” “some Land at Muscongus” in Maine, and “property at Bromfield [Brimfield] & Sturbridge.”

But my understanding is that the Phips mansion standing on that land in East Cambridge hadn't been occupied for some years prior to Lechmere's inheritance, and I don't think he ever lived there himself. It was in a remote location with no easy access, often becoming an island at high tide.

The Cambridge residence I associate with Richard Lechmere was the Tory Row house on Brattle Street, which he built circa 1761. In 1771 Lechmere sold that house to Jonathan Sewall, who still owned it in 1774-75. About the same time, Lechmere bought an estate residence in Dorchester, from Thomas Oliver, who had moved to Cambridge shortly before that. But it appears that Lechmere only owned that Dorchester house for about eight months, before selling it to an Ezekiel Lewis, who in turn quickly resold it to John Vassall [Jr.], another Tory Row resident. (And as you know, John, the Vassall, Oliver, Lechmere, and Phips families were all intermarried with each other.)

Lechmere may have purchased the Dorchester property with the intent of moving there, but since he resold it so quickly, he may never have actually occupied the estate. I believe he may already have relocated to Boston itself by 1772 or so. (I remember reading that somewhere, but can't track the source down right now.) He did own a large distillery in Boston.

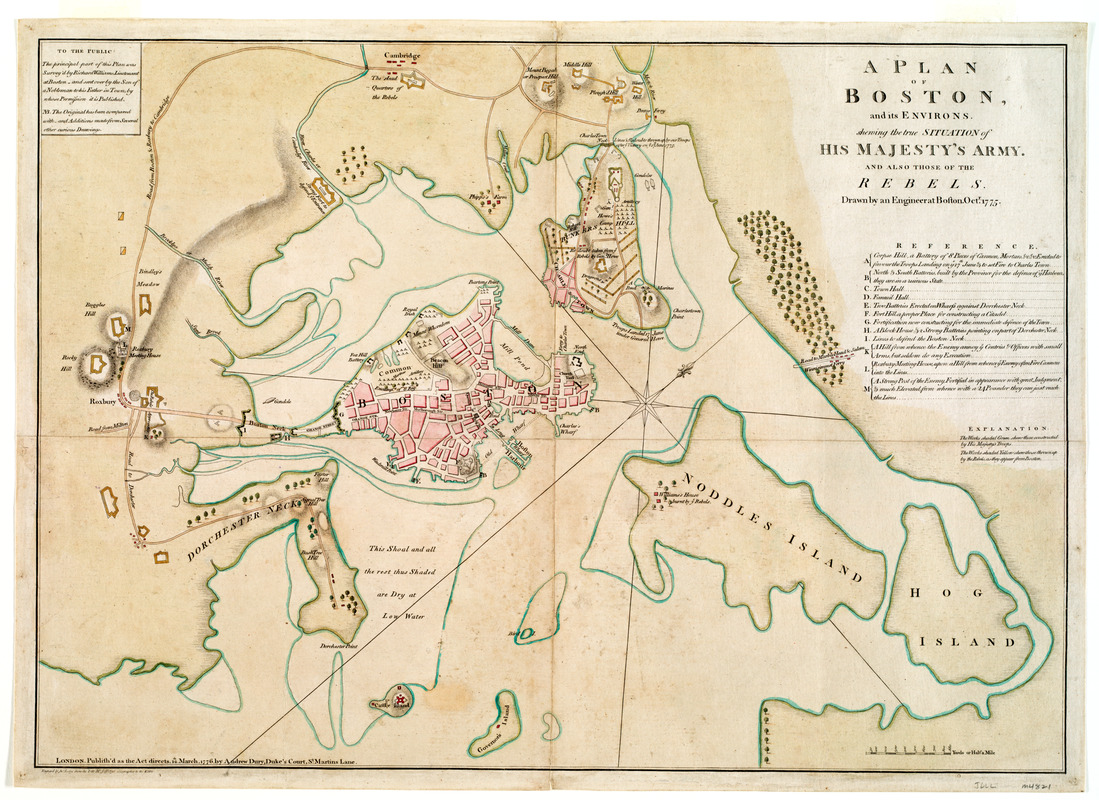

The fact that the Phips mansion in East Cambridge was vacant in 1775 may well have been a reason why Gen. [Thomas] Gage chose that isolated area as the landing place for the Concord expedition on April 18. With no nearby residents, there wouldn't be any nosy neighbors to notice the troops' arrival.

But where did Richard Lechmere live? Some of those properties were real-estate investments. He may have moved between a couple of houses seasonally. But where was his legal residence? I went looking for period sources.

Lechmere’s name (as well as others’) is still attached to his 1760s home on Brattle Street in Cambridge, shown above. But according to Cambridge historian Lucius Paige, Lechmere turned that property over to royal attorney general Jonathan Sewall on 10 June 1771.

The 17 May 1770 Boston News-Letter contains an advertisement for the Dorchester house that had belonged to Thomas Oliver. That ad directed inquiries to “Richard Lechmere, of Cambridge,” meaning he didn’t move to Dorchester, just owned the property there while still living in Cambridge.

On 22 Aug 1773 the Boston Evening-Post contains another advertisement for a house in Boston on Hanover Street, “lately in the Occupation of Jacob Royall, Esq; deceased.” That directs inquiries to “Richard Lechmere, of Boston.” So by that date Lechmere presented himself as back in the town of his birth, no longer a Cambridge resident.

According to James Henry Stark’s Loyalists of Massachusetts, the Boston real estate confiscated from Lechmere was a house, land, and distill-house on Cambridge Street. He may have moved there from Hanover Street, or the house in that second advertisement was another property he managed. Cambridge Street was probably where Richard Lechmere was living when he became a mandamus Councilor—already safe from actual Cambridge residents.