All Things Liberty recently featured new co-editor Don Hagist’s list of

“Top 10 Battles of the Revolutionary War.” The only certainty about that sort of list is that it won’t please everybody, and indeed I was among commenters asking about other “turning-point” battles that didn’t make the cut.

In a lot of those Revolutionary War lists,

I’ve observed, most of the turning-points turn one way—usually for the Americans. But surely the Crown forces enjoyed some turning-points as well. Otherwise, the Americans wouldn’t have needed to turn anything. Don’s list does include some British triumphs, though not a couple that I think are significant.

It turned out, as Don explained his thinking in comments, that he went looking for

battles that changed the course of

campaigns. In other words, the arrival of the British in

New York in 1776 and their victories at

Brooklyn and

White Plains all furthered a successful campaign, but the

turning-point came at

Trenton, where the Continentals finally slowed the British advance.

Thus, Don’s list included the first British attack on Charleston, South Carolina, in 1776, when their

campaign was defeated; but not the

second in 1780, when they took over America’s principal southern port, captured 5,000

Continental soldiers, and established a second garrison within the U.S. of A. that lasted to the end of the war.

I realized I approach turning-points differently, looking for events that changed people’s thinking about the war. But before I continue quibbling, I have to acknowledge that Top Ten lists require

cutting things out. It’s all very well to complain that a movie critic left your favorites off her Top Ten Films of the Year, but to play the same game you have to cross out as many items as you add.

So I’ll start by striking the first battle off Don’s chronological list: the Battle of

Lexington and

Concord. Obviously significant in starting the war, it was nevertheless not a turning-point. It just solidified what each side thought about the situation. For months Gov.

Thomas Gage knew his political authority stopped at the gates of Boston; the

siege militarized the isolation that already existed.

Before 19 Apr 1775, Massachusetts Patriots were already convinced that the royal authorities were out to destroy their ability to defend themselves. The royal forces already believed most New Englanders were a swarm of rebellious zealots. I’m not sure the actual fighting changed many minds. Some provincial

militiamen were pleasantly surprised they could shoot

regulars, but they’d been hearing stories about their region’s triumph at

Louisbourg for months. After the battle, the

Massachusetts Provincial Congress’s communications didn’t emphasize the battlefield victory but the new set of grievances, which they said confirmed what they’d been warning about the Crown all along.

I think the Battle of

Bunker Hill (#2 on Don’s list)

was a turning-point—even though the immediate result in the field also looks small. The British took control of a second peninsula in Boston harbor, but one that the provincials had occupied for less than twenty hours, and then sat on it for nine months. But that bloody fight made both sides rethink things. The Americans were scared, then gradually reassured about their ability to inflict damage on a regular army. The British commanders became convinced that there was no reason to stay in Boston. It took months for the London government to approve their plans to leave, and then winter came on, but the Battle of Bunker Hill really decided the first campaign of the war and changed people’s thinking.

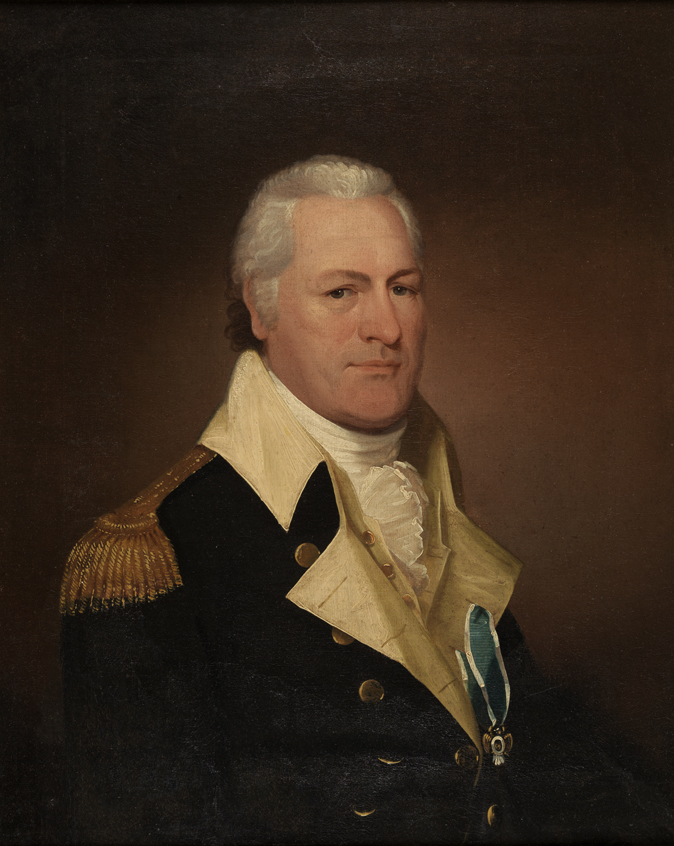

Unfortunately, I think Gen.

George Washington came away from hearing about Bunker Hill with the wrong thinking.

As I wrote back here, he thought the key to the war would be another Bunker Hill—another big battle with lots of enemy casualties that would make the London government pull back. He kept proposing that strategy to his generals around Boston, he hoped the fortification of

Dorchester Heights would lead to such a battle, he waited for the same thing at Brooklyn, and so on.

Which brings me to the Battle of

Brandywine on 11 Sept 1777. That battle didn’t fit Don’s “turning-point” criteria because it was part of Gen.

William Howe’s successful campaign to take Philadelphia; he never had to turn around. The battlefield isn’t part of our

National Park Service system, probably because the Americans lost. (It’s a

Pennsylvania state park instead.) But boy, did it change people’s thinking!

Brandywine was the battle Washington wanted: a direct confrontation with Howe. Huge numbers in the field. The British attacking the Continental position, leaving themselves open to heavy casualties. And it all went horribly wrong. Howe surprised Washington by sneaking around to the left. The Continentals had to fall back. Within weeks, the Crown forces were in Philadelphia.

Now when a country loses its largest city and capital to the enemy a year and a half after declaring independence, that’s bound to change people’s thinking. Combined with the news of

Saratoga (#6 on Don’s list), Brandywine made some members of the

Continental Congress rethink whether Washington should remain commander-in-chief. And frankly, when they had hastily evacuated to Lancaster and York, who could blame them? Washington himself was rethinking. We remember the winter at

Valley Forge for Gen.

Steuben’s training of the Continental core, but that was also when Gen. Washington came around to his “Fabian” strategy. That’s why I see Brandywine as a very big turning-point.

Of course, that won’t please everybody.