Boston’s

Faneuil Hall is different from most other landmarks and monuments bearing

slaveholders’ names because in most cases those sites arose from a later generation choosing to honor a person.

Sometimes that act is meant to elevate a local hero, as in

Albany’s statue of Gen.

Philip Schuyler. Sometimes it’s a way for a locality to bask in the celebrity of an established hero, as in

George Washington High School in San Francisco. And sometimes it’s an attempt to vindicate a particular ideology, as in the

big statue of Robert E. Lee in Richmond, erected in 1890.

But none of those approaches apply to Faneuil Hall.

Peter Faneuil was a wealthy Boston merchant with no

wife or

children who in 1740 offered to pay for a new marketplace and meeting hall. Since a crowd of protesters had destroyed the market building at Dock Square only three years before, that offer required some discussion. The space for

town meetings was obviously an attempt to make the market stalls acceptable. Bostonians barely voted to accept Faneuil’s money.

The new building opened at the old space in September 1742. By this time the town meeting was happy to have it. Future governor Thomas Hutchinson moved that the hall be named after its donor, “at all times hereafter.” The town approved that proposal, also commissioning a portrait by

John Smibert and a Faneuil coat of arms to hang inside.

Peter Faneuil died unexpectedly the following year. He was a major player in Boston’s

business community in the 1730s, and at his death people said he had been charitable. But he played no role in the local historical developments that get the most attention: not the Puritan settlement, not the Revolution, not even the witchcraft trials or first

smallpox inoculations. Most Faneuil family members became

Loyalists.

Aside from funding the hall, I don’t see evidence of Peter Faneuil doing anything else of importance. The Faneuil Hall name is thus more like how Gillette Stadium hypes the highest corporate bidder than like how the Washington Monument honors the

first President.

That name might even give Peter Faneuil too much credit. In January 1761 the building

burned. (This was less than a year after the great fire that started at the Sign of the

Brazen Head.) The town decided to rebuild within the surviving walls, this time adding a slate roof. For funds, the province authorized a

lottery; advertisements for the periodic ticket sales and prize drawings appear throughout the Revolutionary period. But the building was still called Faneuil Hall.

In 1806, that meeting hall was greatly expanded from the 1761 design shown above to its present dimensions, growing both up and out. But the building was still called Faneuil Hall.

In the 1820s the first Mayor

Josiah Quincy pushed for Boston—now a city—to build new stone buildings to the east of the hall, creating much more market space. The central domed building is called Quincy Market. But the whole collection of buildings is called Faneuil Hall Marketplace.

In sum, Peter Faneuil funded the first version of one corner of the smallest of four buildings in the complex, but his name is on the whole thing.

Or is it? We probably don’t remember his name accurately. The Faneuil originally pronounced their name with

French vowels. The British, or more particularly Yankee British, changed that, as I

discussed back here. Smibert,

Robert Love, and other Boston contemporaries wrote it out as “Funnel.” In the nineteenth century people rediscovered some version of the French original, but its spelling and pronunciation remain a special challenge.

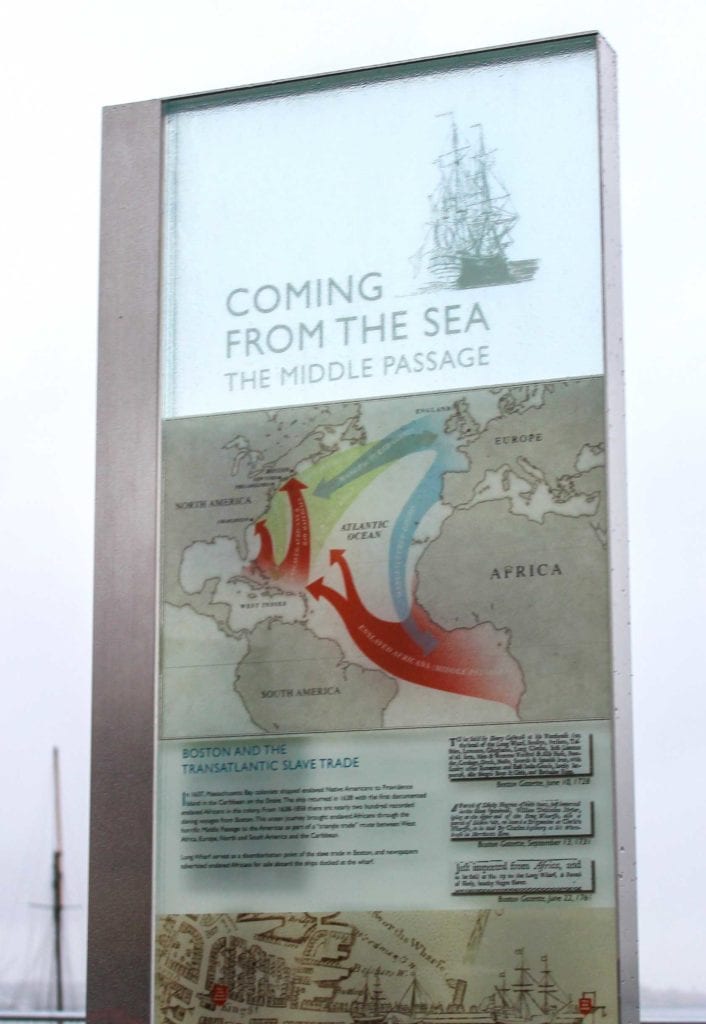

We thus use the Faneuil Hall name not out of admiration for Peter Faneuil and all he was—native

New Yorker, child of Huguenot refugees,

disabled bachelor, Anglican convert, merchant trading with the

Caribbean, slave trader. We use the name simply because that’s what we all grow up calling that building. And the building has become much more famous than its namesake.

Since important Revolutionary events occurred inside that space, the name of Faneuil Hall is in American history books. The site is on the Freedom Trail. It’s an anchor of Boston National Historical Park. And the civic building continues to fulfill its original purpose—drawing customers to the nearby shops.

TOMORROW: So what can we call it?