“A bayonet wrested from one of the pursuers”

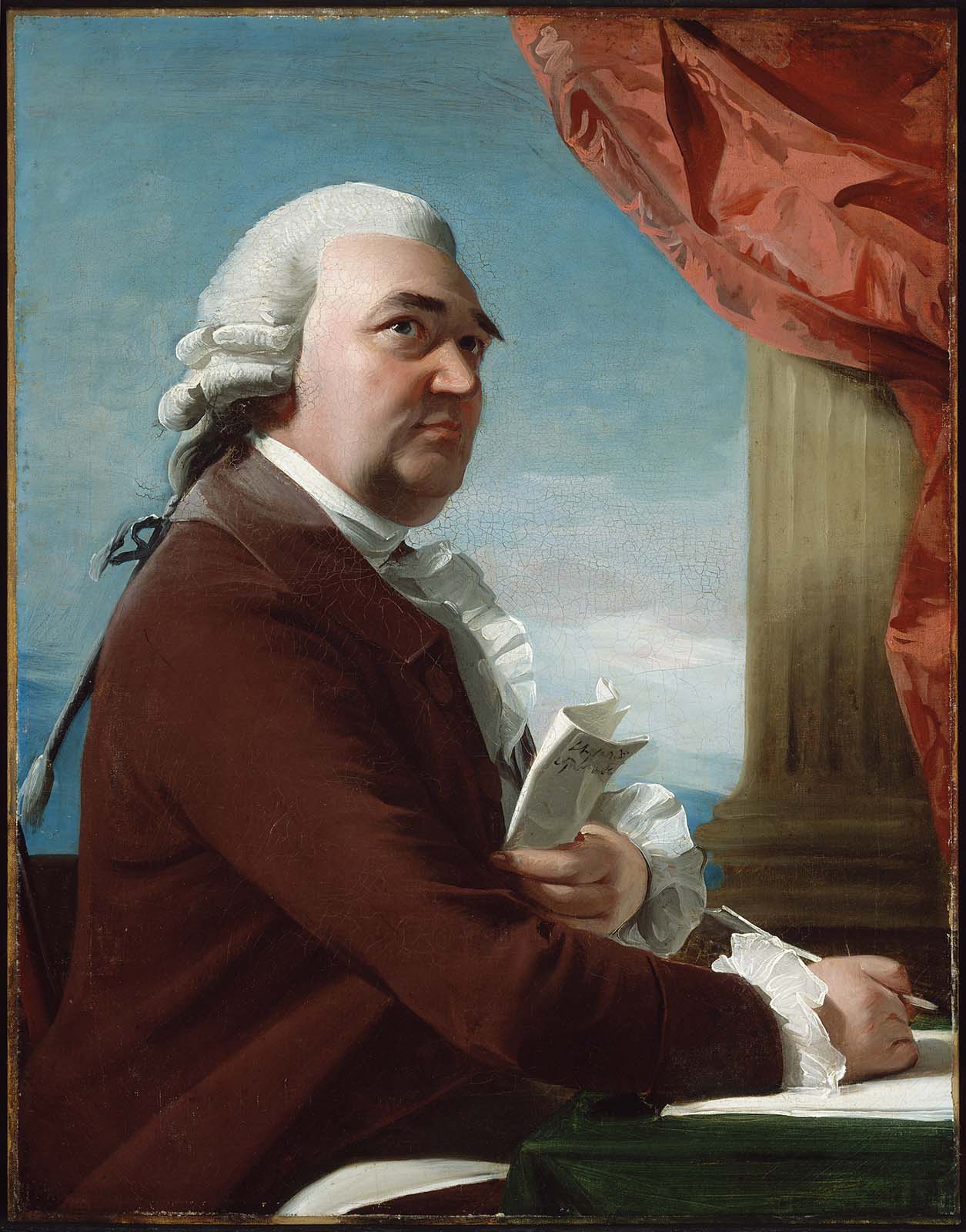

Justice Ruddock was used to getting his way in that neighborhood. He was a big man—probably 300 pounds or more. In September 1766 he told Sheriff Stephen Greenleaf that he was “Unable to Walk far [and] must be Carried in his Chaise.” At that time, Ruddock was rattling off excuses why he couldn’t come help the sheriff and Customs officers search the storehouse of Daniel Malcom for smuggled goods. Because Ruddock was no fan of royal officials.

When the Crown government stationed troops in Boston in 1768, Ruddock was among their most active opponents. He was one of the magistrates who prosecuted Capt. John Willson for allegedly encouraging enslaved Bostonians to revolt. He arrested soldiers for disturbing the peace in both January and February 1769.

Sgt. John Norfolk of the 14th Regiment complained about another such confrontation:

That on or about the 22d. February 1769, in the evening, he heard a great noise in the street; and found it was occasioned by some Soldiers and Inhabitants who were at high words amongst whom was one Ruddock, who said he was a Justice of the peace, and expressed the words, Go fetch my broad sword and Fusee and Damn the Scoundrels, let us drive the Bloody backs to their Quarters, Send for my Company of Men, for I think we are men enough for them.According to Norfolk, Justice Ruddock wasn’t slowed at all by his weight that night. And his son—either John, Jr., or Abiel—yanked him into the family home.

He the deponent did what was in his power to prevent their Quarreling and in striving to part the Soldiers and Inhabitants Received great abuses from a son of the said Ruddocks who took him by the hair and pulled him into a passage leading into the yard of Said Ruddocks house, shutting the Door upon him, and by repeated blows laid him on the ground quite insensible after he came to himself thay opened the door and kick’d him out of the passage, at the same time they took the opportunity of taking him his side, his Bayonet which he wore (being then a Corporol), and which is now in the possession of said Ruddock who hath refused to return it tho’ properly demanded, both by himself and a Serjeant sent By his Captain for that purpose.

Of course, the justice had his own view of the situation. He thought he was keeping the peace in the face of rowdy military men. Here’s how the Whigs reported the same event for newspapers in other colonies:

As some sailors were passing near Mr. Justice Ruddock’s house, the other night, with a woman in company, they were met by a number of soldiers, one of whom, as usual with those people, claimed the woman for his wife; this soon bro’t on a battle in which the sailors were much bruised, and a young man of the town, who was only a spectator, received a considerable wound on his head; a great cry of murder, brought out the justice, and his son, into the street; when the former who is a gentleman of spirit, immediately laid his hands upon two of the assailants, and called out to one who pretended to be an officer, and all other persons present, requiring them in his Majesty’s name to assist him as a magistrate, in securing those rioters;The bayonet that the Ruddocks came away with is the link between these two accounts.

instead of this, he was presently surrounded with thirty or forty soldiers, who had their bayonets in their hands, notwithstanding the unseasonable time of night; some of whom endeavoured to loose his hold of the persons he had seized, but not being able to do it, they then made at him with their fists and bayonets; when he received such blows as obliged him to seek his safety by flight;

they struck down a young woman at his door holding out a candle, and followed him and son into the entry-way of his house with their bayonets, uttering the most profane & abusive language, and swearing they would be the death of them both;

upon the first assault given to the magistrate, one of the persons present posted away to the Town-House, and acquainted the commanding officer of the picquet guard, of what was taking place; but it seems the officer did not apprehend himself at liberty to order a party out to secure, or disperse those riotous drunken soldiers.

Due enquiry is making for the discovery of those daring offenders, in order to their being presented to the grand jury, a bayonet wrested from one of the pursuers in the entry, may lead to a knowledge of the owner, and be a means of procuring proof.

On 27 March, the Whigs reported a grand jury had brought charges “against a number of soldiers, for assaulting with drawn cutlasses and bayonets; smiting and wounded [sic], John Ruddock, Esq; one of his Majesty’s justices of the peace, when suppressing a riot at the north part of the town, late at night, in which they were actors.”

As of 21 April the royal judges still hadn’t begun that trial, the Whigs reported, “nor has any thing been done upon it, as we can yet learn.” Norfolk said nothing about being tried, so probably the whole matter dropped, leaving everyone angry.