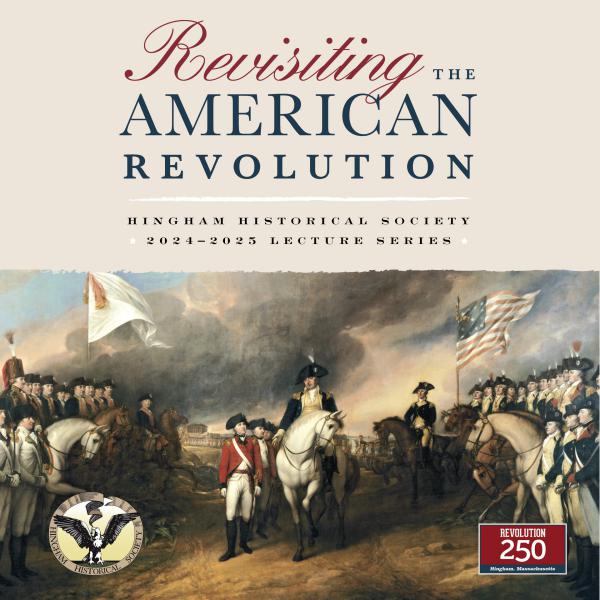

The Hingham Historical Society is hosting a

series of seven lectures from September through April 2025 on the theme of “Revisiting the American Revolution.”

I’m honored to be one of those speakers, and a bit humbled to see the others in the lineup.

15 September

1774: The Long Year of Revolution

Mary Beth Norton

Norton is the Mary Donlon Alger Professor of American History Emerita at Cornell University, where she taught from 1971 to 2018. She has written seven books about early American history, including

Liberty’s Daughters: The Revolutionary Experience of American Women, 1750-1800 and

In the Devil’s Snare: The Salem Witchcraft Crisis of 1692. She was a coauthor of

A People and A Nation, one of the leading U.S. history textbooks. Her most recent work, the basis for this talk, won the 2021 George Washington Prize.

27 October

Making Thirteen Clocks Strike as One: Race, Fear, and the American Founding

Robert Parkinson

Parkinson is Professor of History at Binghamton University. He is the author of

The Common Cause: Creating Race and Nation in the American Revolution, and most recently,

Heart of American Darkness: Bewilderment and Horror on the Early Frontier.

17 November

The Spies in Henry Barnes’s House

J.L. Bell

Bell is the author of

The Road to Concord: How Four Stolen Cannon Ignited the Revolutionary War, a National Park Service report on Gen. George Washington in Cambridge, and numerous articles. He maintains the Boston 1775 website, offering daily postings of history, analysis, and unabashed gossip about the American Revolution in New England.

8 December

From Hingham to Yorktown: The Military Campaigns of General Benjamin Lincoln

Robert Allison

Allison is a professor of history at Suffolk University. His books include a biography of American naval hero Stephen Decatur, and short books on the history of Boston and the American Revolution, and an edition of

The Interesting Narrative of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African. Two of his classes, “Before 1776: Life in Colonial America,” and “The Age of Benjamin Franklin” are available from The Great Courses. As chair of Revolution 250, a consortium of organizations planning Revolutionary commemorations in Massachusetts, he hosts its

weekly podcast, and he is president of the

Colonial Society of Massachusetts.

26 January 2025

Hingham’s Revolutionary Canteens

Joel Bohy

Bohy is the director of Historic Arms & Militaria at Bruneau and Co. Auctioneers and a frequent appraiser of Arms & Militaria on the PBS series

Antiques Roadshow. His is also an active member of several societies of collectors and historians, an instructor for Advanced Metal Detecting for the Archeologist, and an advisory board member of American Veterans Archaeological Recovery. Growing up in Concord, Massachusetts, helped lead to Bohy’s passion for historic arms & militaria, conflict archaeology, and artifacts like Hingham’s historic Revolutionary War canteens.

9 March

How to Radicalize a Moderate: John Hancock and the Outbreak of the Revolutionary War

Brooke Barbier

Barbier is a public historian with a Ph.D. in American History from Boston College. She is the author of

King Hancock: The Radical Influence of a Moderate Founding Father and

Boston in the American Revolution: A Town Versus an Empire. Because she believes beer makes history even better, she founded

Ye Olde Tavern Tours in 2013, a popular guided outing along Boston’s renowned Freedom Trail.

6 April

The Declaration of Independence: A Guide for Our Times

Danielle Allen

Allen is James Bryant Conant University Professor at Harvard University and Director of the Allen Lab for Democracy Renovation at Harvard Kennedy School’s Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation. She is a professor of political philosophy, ethics, and public policy. She is also a seasoned nonprofit leader, democracy advocate, tech ethicist, distinguished author, and mom. Her many books include the widely acclaimed

Our Declaration: A Reading of the Declaration of Independence in Defense of Equality, and she writes a column on constitutional democracy for the

Washington Post.

All these talks will take place live beginning at 3:00 P.M. on a Saturday at the Hingham Heritage Museum, and also be streamed online. The society is now selling subscriptions to the entire series for prices ranging from $175 for someone who’s already a member to $675 for someone who wants to become a society Steward. The subscription price for non-members is $200, or about $29 apiece.

.jpeg)