“Capt. Malcom of this Place, who was taken by a French Privateer”

That presented dangers for merchant captains like John and Daniel Malcom, as well as opportunities.

In seeking British government assistance years later, John Malcom declared:

I have had thirteen Different Commissions in your Majesty’s Land Service in North America the two last French and Spanish warrs that is Past. I have Serv’d from a Ensign to a Colonel. I have been in all the Battles that was Fought in North America those two warrs that is Past except two and at every Place we Conquerd and Subdued our Enemys to your Majesty.That’s quite a claim, and he didn’t provide any specifics. Were his “Commissions” in the militia, in a colonial army, as a privateer captain, or even as a contractor?

That vagueness makes it hard to figure out where John Malcom was when his surname appears in Boston newspapers. For example, the 6 Oct 1755 Boston Gazette had a supplement with news of two men missing from “Capt. Malcom’s Company” in Maj. Joseph Frye’s force after the Battle of Petitcodiac in what’s now New Brunswick. What that John Malcom, a relative, or someone with no connection?

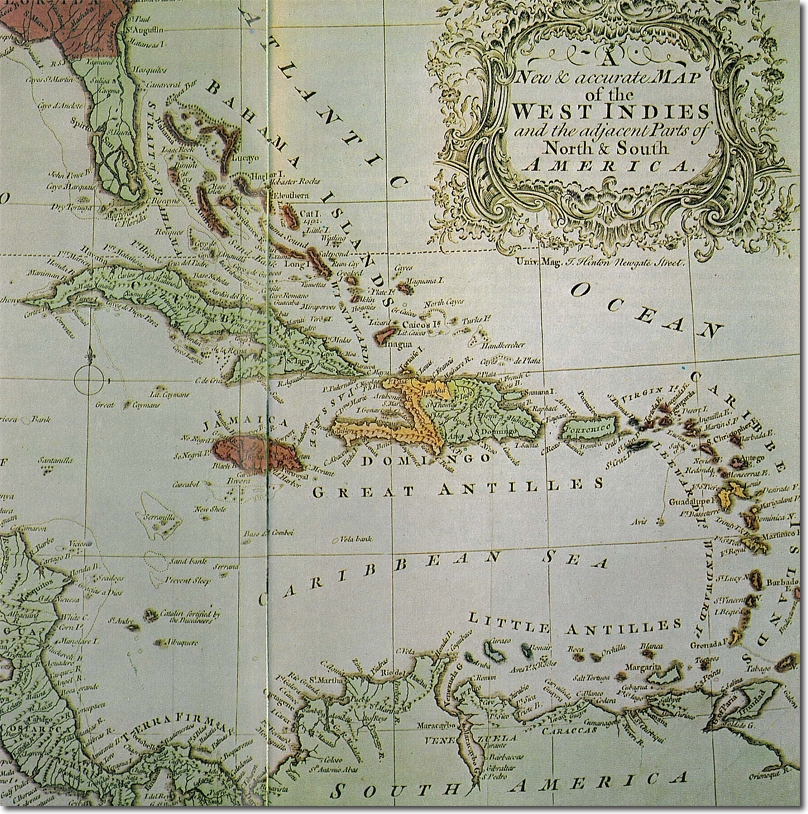

The 23 Dec 1756 Boston News-Letter reported that a French schooner had captured a “large Sloop, belonging to Carr and Malcolm,” in Martha Brae Harbour on Jamaica. Was that ship partly owned by John Malcom? Or might that owner have been a merchant from distant Scotland?

Adding to the fog is how John’s younger brother Daniel was also a ship’s captain. The 30 May 1757 Boston Gazette reported this adventure for one of the brothers, but which one?

Thursday last came to Town Capt. Malcom of this Place, who was taken by a French Privateer and carried into Port au Prince, from whence he got to Jamaica, and informs, that just as he came away Advice was receiv’d there, that 18 Sail of French Men of War and Transports, and about 7000 Troops, was arriv’d at Port au Prince, very sickly.I’m struck by how the Boston press referred to “Capt. Malcom of this Place” as if there were only one. Did that mean that John was serving in an army, so Daniel was the only one commanding a ship? Had one of the brothers moved out of Boston, as John would later do? Or was that just sloppy reporting?

On 4 May 1758 the Boston News-Letter reported:

The ———, Vavason, from New York, and the ———, Malcom, from Boston, for Madeira, are taken and carried into Louisbourg.Not only was that news item short on details, but it came from London, so it was months old. But it couldn’t have been over a year old and refer to the same capture as the last article.

Fortunately, in the summer of 1758 the British Empire took Louisbourg from the French (again). After that, it’s easier to spot John Malcom.

TOMORROW: Back and forth.