“Complying with her constitution’s earnest call”

In 1748 Robinson started sharing a house in Bath with Lady Barbara Montague (c. 1722–1765). This lady’s Montague family was different from the Montagu family that Sarah’s sister married into.

Two years later, Robinson penned her first novel, The History of Cornelia—published, like all her work, anonymously or pseudonymously, and for money.

In 1751 Sarah Robinson married George Lewis Scott (1708–1780), one of George III’s instructors—a job she had helped to secure for him, apparently.

However, that marriage broke up within a year, with the Robinson family stating it was never consummated. The unhappy couple grumbled about each other for the rest of their lives. (George Lewis Scott would later introduce Thomas Paine to Benjamin Franklin, but that’s another story.)

The woman now called Sarah Scott went back to “Lady Bab” in Bath and back to earning money with her pen. By the end of that decade she was also translating from the French, creating educational materials, writing history books about Protestants on the continent. Scott’s most successful novel appeared in 1762: A Description of Millenium Hall and the Country Adjacent. Almost everything she wrote had a moralizing element.

By 1778 Lady Bab had died, but Sarah Scott had gained a comfortable income through family gifts and inheritance. She stopped publishing, but she kept up her lively literary correspondence with her sister.

In October of that year, Catharine Macaulay left Bath for Leicester, and the next month word got back that the celebrated historian had married William Graham. But that wasn’t all people heard.

On 27 November, Sarah Scott sent this news to Elizabeth Montagu, as transcribed in The Correspondence of Catharine Macaulay, edited by Karen Green:

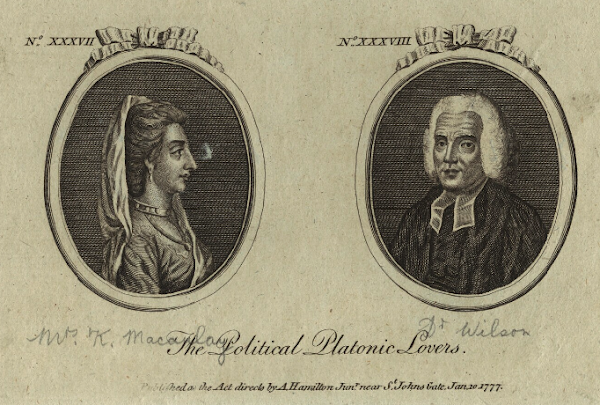

Mrs Macaulay’s marriage was reported in good time to change conversation, of which the Duel between the two gaming counts had been the sole topic, and it was entirely worn out.In other words, Macaulay had discovered that all those medical symptoms that had crippled her for years—fatigue, weakness, “pains in my ears and throat,” “irritations of my nerves,” and above all “a Billious intermitting Autumnal fever”—would go away when she had sex. Really good sex. Sex with a man less than half her age just returned from the sea. Sex that her doting seventy-five-year-old patron, the Rev. Dr. Thomas Wilson, simply wouldn’t have been able to supply.

A Gamester appears to me so far from being a loss to the world that I consider the marriage as the more melancholy event of the two, because it is a dishonor to the sex. If I had not more pride than revengefulness in my temper I might derive much consolation from the moral certainty that her punishment will equal her offence.

The man she has married is in age about 22, in rank 2nd Mate to the Surgeon of an India man. He is brother to a Dr [James] Graham, who etherized and electrified her, till he has made her electric per se.

She wrote a letter to Dr Wilson acquainting him with her marriage, and her reasons for it, which she tells him in the plainest terms are constitutional; that she had been for some years struggling with nature but found that her life absolutely depends on her complying with her constitution’s earnest call (perhaps she calls it nature’s, but I shall not, for it is not the nature of woman, and woman cannot find her excuse in the nature of a beast) and she would have chosen him, if his age, as he must be sensible, did not disqualify him for answering a call so urgent.

Which of course ticked Wilson off, as Scott’s letter went on to describe:

The Doctor shews the letter, but I have not seen it, and the Gentlemen declare it cannot be shown to a woman. Old Wilson is rewarded for his folly; he is in the highest rage, and having some years ago by Deed given her the furniture of the house they lived in and 300 peran[num] for her life, he intends to apply to the law to be released from this engagement; on pretence of its having been given without value received. It will make a curious cause, . . .Given Sarah Scott’s own unorthodox domestic history, perhaps she shouldn’t have looked down on Catharine Macaulay’s choice of a second husband. But, as the two poems that Christopher Anstey shared a week later demonstrate, all the fashionable people in Bath were gossiping about the Grahams.

If there is any zeal still remaining in the world for virtue’s cause the pure Virgins and virtuous Matrons who reside in this place, will unite and drown her in the Avon, and try if she can be purified by water, for Dr Graham’s experiments have shown that fire has a very contrary effect on her, being a Salamander it is the element truly congenial to her. Were she flesh and blood one could not forgive her, but being only skin and bone she deserves no mercy.

COMING UP: The lawsuit.