The Changing Image of Catharine Macaulay

In the mid-1760s, as I wrote yesterday, Catharine Macaulay became an icon for British Whigs.

Her History of England from the Accession of James I reinforced the Whiggish story of restoring and preserving ancient British liberties from the tyrannical encroachments of the Stuart monarchs.

Macaulay herself was from a respectable family, the sister of a Member of Parliament, after 1766 the widow of a physician with a young daughter. She wasn’t conventionally beautiful, with her thin face and long nose, but that face made her quickly recognizable.

The National Portrait Gallery in London shares some engraved images of Macaulay from this period, such as the one shown above, framing her as a matron from the Roman republic. Another print spelled out that linkage.

In the late 1760s, however, Macaulay’s public image began to change. The more she wrote about the English Civil War and the Commonwealth, the more radical she seemed. Then in 1774 she moved into the Rev. Dr. Thomas Wilson’s house in Bath, as discussed back here. And of course she was a woman in the public eye.

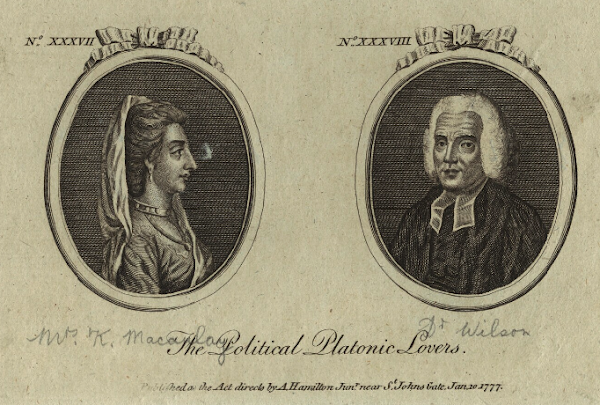

Those developments raised questions in people’s minds, which came out in this engraving issued in 1777, a double portrait of Macaulay and Wilson titled “The Political Platonic Lovers.” That label swirled together the two reasons people might look askance at Catharine Macaulay: her politics and her living arrangement.

Over the next couple of years, Wilson commissioned Robert Edge Pine to paint a portrait of Macaulay holding one of her letters to him. He commissioned Joseph Wright of Derby to paint himself and Macaulay’s daughter. He commissioned John Francis Moore to sculpt a statue of Macaulay as the muse Clio, which he eventually pressed upon the church he was supposed to be serving in London. He published odes to Macaulay on her forty-sixth birthday in 1777 from himself, the teenager Richard Polwhele, and Dr. James Graham. Clearly the minister was besotted with the historian.

Macaulay obviously appreciated the house to live in and the promised bequest to her daughter. But she resisted any offers or hints of marriage from Wilson. She maintained that the septuagenarian minister was merely a friend. Indeed, when she published the first volume of a less formal History of England from the Revolution as “a Series of Letters to a Friend,” that friend was Wilson.

In those same years, Macaulay was struggling to continue her history of 17th-century England; no volume had appeared since 1771. She was feeling sick much of the time. That was how she had become a patient and patron of Dr. Graham, who presented himself as an eye specialist with extra-special training from America.

Given her personal state, Macaulay surely would not have appreciated this crude colored print published later in 1777 and now digitized by the British Museum. Captioned “A Speedy and Effectual Preparation for the Next World,” the picture shows the historian, recognizable by her long nose, putting on her makeup as Death shakes sand out of an hourglass. A portrait of the Rev. Dr. Wilson hangs above her table.

TOMORROW: A journey for her health.

Her History of England from the Accession of James I reinforced the Whiggish story of restoring and preserving ancient British liberties from the tyrannical encroachments of the Stuart monarchs.

Macaulay herself was from a respectable family, the sister of a Member of Parliament, after 1766 the widow of a physician with a young daughter. She wasn’t conventionally beautiful, with her thin face and long nose, but that face made her quickly recognizable.

The National Portrait Gallery in London shares some engraved images of Macaulay from this period, such as the one shown above, framing her as a matron from the Roman republic. Another print spelled out that linkage.

In the late 1760s, however, Macaulay’s public image began to change. The more she wrote about the English Civil War and the Commonwealth, the more radical she seemed. Then in 1774 she moved into the Rev. Dr. Thomas Wilson’s house in Bath, as discussed back here. And of course she was a woman in the public eye.

Those developments raised questions in people’s minds, which came out in this engraving issued in 1777, a double portrait of Macaulay and Wilson titled “The Political Platonic Lovers.” That label swirled together the two reasons people might look askance at Catharine Macaulay: her politics and her living arrangement.

Over the next couple of years, Wilson commissioned Robert Edge Pine to paint a portrait of Macaulay holding one of her letters to him. He commissioned Joseph Wright of Derby to paint himself and Macaulay’s daughter. He commissioned John Francis Moore to sculpt a statue of Macaulay as the muse Clio, which he eventually pressed upon the church he was supposed to be serving in London. He published odes to Macaulay on her forty-sixth birthday in 1777 from himself, the teenager Richard Polwhele, and Dr. James Graham. Clearly the minister was besotted with the historian.

Macaulay obviously appreciated the house to live in and the promised bequest to her daughter. But she resisted any offers or hints of marriage from Wilson. She maintained that the septuagenarian minister was merely a friend. Indeed, when she published the first volume of a less formal History of England from the Revolution as “a Series of Letters to a Friend,” that friend was Wilson.

In those same years, Macaulay was struggling to continue her history of 17th-century England; no volume had appeared since 1771. She was feeling sick much of the time. That was how she had become a patient and patron of Dr. Graham, who presented himself as an eye specialist with extra-special training from America.

Given her personal state, Macaulay surely would not have appreciated this crude colored print published later in 1777 and now digitized by the British Museum. Captioned “A Speedy and Effectual Preparation for the Next World,” the picture shows the historian, recognizable by her long nose, putting on her makeup as Death shakes sand out of an hourglass. A portrait of the Rev. Dr. Wilson hangs above her table.

TOMORROW: A journey for her health.

No comments:

Post a Comment