“One of the schools which I was in when I was here before”

Back in the spring of 1780, John Quincy returned to a small school in Passy, France, taught by a man named Péchigny. In 1771 that gentleman had issued a prospectus for an “école de mathématiques, de belles-lettres, d’arts libéraux et cours de langues”—a school of mathematics, belles-lettres, liberal arts, and language courses.

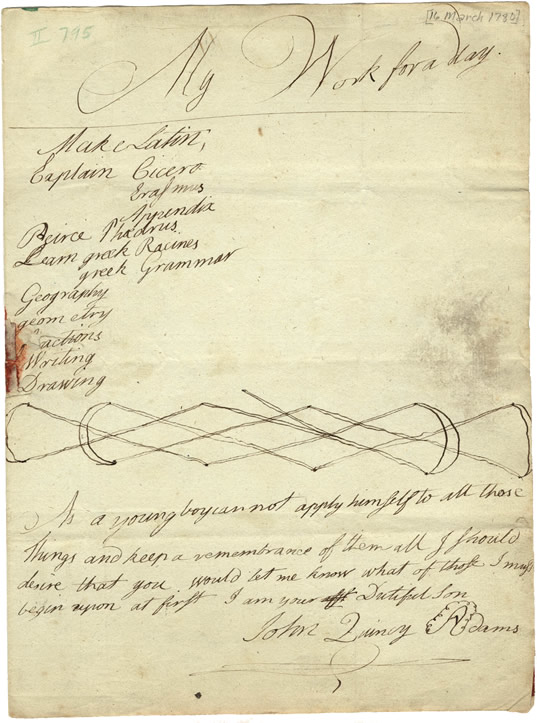

Soon after starting, the twelve-year-old sent a report to his father listing “My Work for a day”:

Make Latin,“Writing” meant handwriting practice, not composition. “Drawing” was likewise an exercise in penmanship, and John Quincy demonstrated by bridging the page with an ornamental design.

Explain Cicero

Erasmus [Colloquia]

Appendix [Appendix de Diis et Heroibus ethnicis]

Peirce [i.e., parse] Phaedrus [Fables]

Learn greek Racines [i.e., roots]

greek Grammar

Geography

geometry

fractions

Writing

Drawing

But this letter wasn’t just showing off. John Quincy finished by humbly asking his father for advice on what subjects to concentrate on:

As a young boy can not apply himself to all those Things and keep a remembrance of them all I should desire that you would let me know what of those I must begin upon at first.When you asked John Adams what you should do, you got an answer. On 17 March he told Johnny to keep at the Latin and Greek as M. Péchigny told him. “Writing and Drawing are but Amusements and may serve as Relaxations from your studies.” And as to the mathematical subjects, he wrote, “I hope your Master will not insist upon your spending much Time upon them at present”; even elite New England schools left off geography and geometry until college.

I am your Dutiful Son,

John Adams didn’t stop there, though. He also critiqued his eldest son’s letter-writing technique. “You should have dated your Letter,” he wrote at the top. And a postscript added, “The next Time you write to me, I hope you will take more care to write well. Cant you keep a steadier Hand?”

The editors of the Adams Papers published images of John Quincy’s letters before and after this one to show how much more care the boy then took to make his handwriting neat for his father. (He was already being much more neat in letters home to his mother.)

Another glimpse of John Quincy’s attitude toward schooling appears in a letter he wrote to a cousin on 17 March, the same date as his father’s reply.

I am in one of the schools which I was in when I was here before and am very content with my situation. I will give you an account of our hours.Thus, John Quincy (and his brother Charles) was at study eight and a half hours of the day in Passy. His afternoon snack consisted of “a piece of dry bread.” And he was “very content.”

At 7 o clock A.M. we get up and go in to school and at 8 o clock we breakfast which consists of bread and milk. At 9 go into school again, stay till one when we dine, after dinne[r] play till half after two, go into school and stay till half after 4 and then we have a peice of dry bread. At 5 we go into School and stay till 7 when we sup, after supper we amuse ourselves a little and go to bed at 9 o clock.

This was not a boy to complain about a school for petty reasons.

TOMORROW: At the Latin School on the Singel.