For and Against the Committee of Correspondence

But the merchant John Rowe did.

In his diary, Rowe listed the defenders of the standing committee of correspondence as:

- Samuel Adams.

- Dr. Joseph Warren.

- William Molineux.

- Josiah Quincy, Jr.

- Dr. Thomas Young.

- Benjamin Kent (1708–1788), a lawyer. He was a Whig, but he had Loyalist relatives and after the war he actually moved to Canada to be with his children.

Speaking “against the Behaviour of the Committee” were:

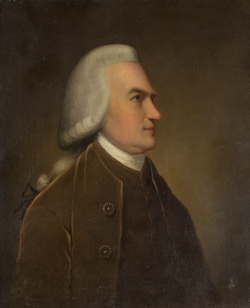

- Harrison Gray (1711–1794, shown here), treasurer of Massachusetts, merchant.

- Thomas Gray (1721–1774), merchant, elected to the General Court for one term in 1764, half-brother to Harrison Gray.

- Samuel Elliot (1739–1820), merchant, later president of the Massachusetts Bank.

- Samuel Barrett (1722–1798), merchant, occasional town official, later a justice of the peace.

- John Amory (1728–1803), merchant, owner of a distillery.

- Edward Payne (1721-1788), merchant, shot during the Boston Massacre, later in marine insurance.

- Francis Green (1742–1809), merchant, British army veteran.

- Ezekiel Goldthwait (1710–1782), insurance broker, former town clerk, clerk of the courts, registrar of deeds.

We don’t know what paths Thomas Gray would have chosen when war broke out and when the British military left Boston because he died after a carriage accident in November 1774. But we do known the political choices of all the other men.

Harrison Gray, Amory, and Green left Boston with the redcoats, becoming Loyalists. Amory and Green eventually returned to Massachusetts, however.

Elliot, Barrett, Payne, and Goldthwait stayed in Massachusetts, some serving in civic offices under the new republican order. Barrett appears to have thrown in with the Patriots just a couple of months after this town meeting, participating in the Suffolk County Convention and taking on wartime tasks for the state. In contrast, Goldthwait retired from public life.

The argument of this group was likely that, while it was important to stand up for liberty and protest unjust laws, the Boston committee of correspondence’s methods had been too confrontational and led the town into trouble. It was time to back off, settle accounts for the Tea Party, and reopen for business.

John Rowe himself wrote privately: “the Committee are wrong in the matter. The Merchants have taken up against them, they have in my Opinion exceeded their Power.” But he didn’t speak up in the meeting himself.

COMING UP: Mutual resentments.