“About 18 years old, uncommonly large of his age”

I couldn’t find anything more about that child, but Wayne Tucker of the Eleven Names Project spotted a newspaper advertisement that must refer to him under a different name.

On 4 July [!] 1798, the Columbian Centinel ran this ad:

ONE DOLLAR REWARD.The same notice ran again a week later.

RAN away from the Subscriber on the morning of the 21st inst. [i.e., of this month] an indented Molatto Servant by the name of Dick Welsh, about 18 years old, uncommonly large of his age; carried off with him a new broad cloth Coat; a chocolate colour’d short Coat; one fustian short coat; a drab colour’d cloth great coat almost new; one spotted velvet and several other Waistcoats; 3 pair tow Trowsers; 2 pair nankin Overhalls; 3 new tow Shirts; 1 linen do. 2 round Hatts, &c. &c. Whoever will apprehend said ran away and return him to the Subscriber at Jamaica Plains (Roxbury,) shall be entitled to the above reward.

All masters of vessels and others are hereby cautioned against harbouring or concealing said ran away, if they wish to avoid the penalty of the law.

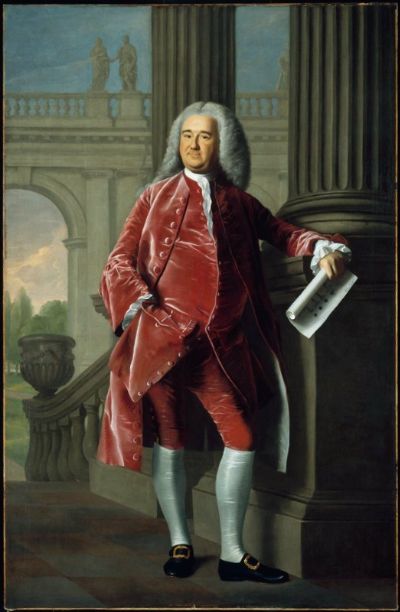

DAVID S. GREENOUGH

Roxbury, June 25, 1798.

Both little Dick Morey and this teenager called Dick Welsh were born in 1780 and “Molatto.” It’s so unlikely that Greenough had two indentured servants matching that description, both named Dick, that this advertisement must refer to the same person.

Among the notable details in this ad is the phrase “about 18 years old, uncommonly large of his age.” That’s a reminder that people reached puberty later in the early modern period, so eighteen-year-old males still had significant physical growth ahead of them. It also gives us a peek at Dick Welsh as an individual.

The advertisement said Welsh took away a lot of clothing—far more than listed in similar ads. He probably planned to sell most of those garments to have money for a longer trip. All told, that clothing was worth more than the dollar Greenough was offering for his indentured teenager—I’ll discuss that promised reward later.

Back in 1785 Greenough and John Morey referred to this child as “known by the Name of Dick”; most slaves were not acknowledged to have surnames. But a year later Dick’s relationship to Greenough was put on a new legal basis when the selectmen indentured the boy, and they called him “Dick Morey.” Twelve years after that, Greenough stated he was “Dick Welsh.”

It wasn’t unusual for African-Americans to change their names in this period (or to convince the authorities to refer to them by names they were already using) as they developed their own identities, no longer bound to masters.

I wondered if the Morey surname implied something about this boy’s father, but the selectmen may simply have chosen it because John Morey was Dick’s last owner. As for the new surname “Welsh,” did that indicate the boy had a familial tie to a man in Roxbury named Welsh (or Welch, or Walsh, or even Weld)? Was it an ethnic signifier for a father in town during the war? Or did Dick adopt that name out of admiration for someone? We don’t know.

The second advertisement indicates Dick Welsh was still free as of 11 July—almost three weeks after he left Greenough’s house. It’s possible he came back, or was made to come back, to serve out his term until age twenty-one. It’s also possible he made good his escape.

TOMORROW: Rewards for runaways.