Having discussed what Boston’s Latin School boys were studying, I now turn to the bigger question: what the larger crowd of Writing School boys were taught. Boston had three public Writing Schools, one on Bennet Street in the North End, one on West Street near the Common, and one in what later became Scollay Square. Together they contained four times the number of boys as the two Latin Schools in 1770.

Having discussed what Boston’s Latin School boys were studying, I now turn to the bigger question: what the larger crowd of Writing School boys were taught. Boston had three public Writing Schools, one on Bennet Street in the North End, one on West Street near the Common, and one in what later became Scollay Square. Together they contained four times the number of boys as the two Latin Schools in 1770.

The main subject at the Writing Schools was—no surprise—writing. Writing five-paragraph essays? Writing book reports or short stories or political essays? Nope. Literally, the main lesson plan was learning to write beautifully with a quill pen.

As Ray Nash stated in American Writing Masters and Copybooks: History and Bibliography Through Colonial Times, published by the Colonial Society of Massachusetts in 1959:

The writing master was ready to show him [the scholar] how to hold the pen properly between fingers and thumb, how to sit correctly at the desk, where to place the paper or ruled writing book in front of him.

Then came the demonstration of the strokes of the letters in due order, of the letters themselves, and eventually of the letters joined into words and the words arranged in improving sentences that are still remembered in the pejorative term “copybook maxims.”

The master wrote the model for the lesson at the top of a fresh page in the learner’s writing book—this was called setting the copy. It was then the pupil’s business to reproduce the copy as nearly as he could, studying each thick and thin, every curve and join, line after line to the bottom of the page under correction of the master.

Much of the master’s time was occupied in the making and mending of pens.

Diderot’s

Encyclopédie offers us illustrations of the

proper posture and tools for writing and

how to cut a quill pen.

For their advanced students, the Writing School masters copied elaborate pages from books, particularly George Bickham’s

Universal Penman, published in London in installments in the early 1740s. Here are two

large examples of Bickham’s model pages, both on the theme of writing itself. You can also view a bunch of smaller Bickham page images from

Davidson Galleries, and two more

examples from DK Images.

Above is a facsimile of a smaller Bickham production,

The Young Clerk’s Assistant, or Penmanship made easy. This edition has been

reprinted by Sullivan Press, which makes a specialty of the

paperwork forms and manuals of the Revolutionary War. The title page alone shows how many styles of handwriting which a gentleman and/or businessman was expected to know.

The 1748 edition of George Fisher’s

The American Instructor, published by

Benjamin Franklin in Philadelphia, included five styles of writing:

- “the Italian Hand”: slanted, flowing, with spiral flourishes

- “the secretary Hand”: upright, thick, old-fashioned

- “An easy copy for Round Hand”: slanted but thicker, with less pronounced flourishes

- a “Flourishing Alphabet”: all capital letters

- a neat style of printing

With all correspondence conducted by handwritten letters, all financial accounts kept by hand, and no practical way to copy documents but to rewrite them, a man in business did a lot of writing. Furthermore, if that man had pretensions to be a gentleman, his handwriting, like the way he dressed and carried himself, was supposed to show effortless grace and propriety. Therefore, smooth, clear handwriting was a valuable skill in colonial American society.

Boston’s Writing Schools also taught the “ciphering,” or arithmetic, that young businessmen would need to know, such as long division, “vulgar fractions,” “the rule of three,” “tare and trett,” “single fellowship,” &c. Thanks to the Georgia state government, we can page through a

copybook created by Thomas Perry, Jr., in 1793, which lays out many mathematical processes in a flourishing hand. (At the end of Perry’s book are examples of another thing Writing School students probably practiced copying: exemplary business documents. As far as I can tell, the boys were never encouraged to compose anything original.)

Many Boston boys who dropped out of a Latin School started going to a Writing School instead; that was the path traveled by

Samuel Breck. Others, such as

William Molineux, Jr., and

Thomas Handysyd Perkins, seem to have spent their entire scholastic careers in Writing Schools, preparing for the business world.

Even for the boys left in Latin School, good handwriting was such an important skill that they often took writing lessons during their midday dinner breaks or at the end of their school days. Such Latin School boys as

John Hancock,

Joshua Green, and

Harrison Gray Otis took such private lessons from writing masters.

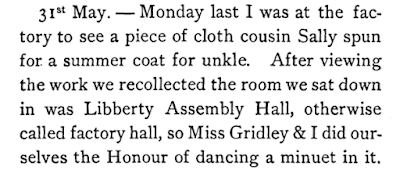

And boys weren’t the only young people who needed good handwriting. Upper-class women were expected to write neatly, too.

Anna Green Winslow was one girl who attended Master

Samuel Holbrook’s private writing lessons, at least when the weather was good.