“On the Alarm being given…”

On 30 December, Gen. Thomas Gage set out this plan for his garrison in case they were attacked from the countryside:

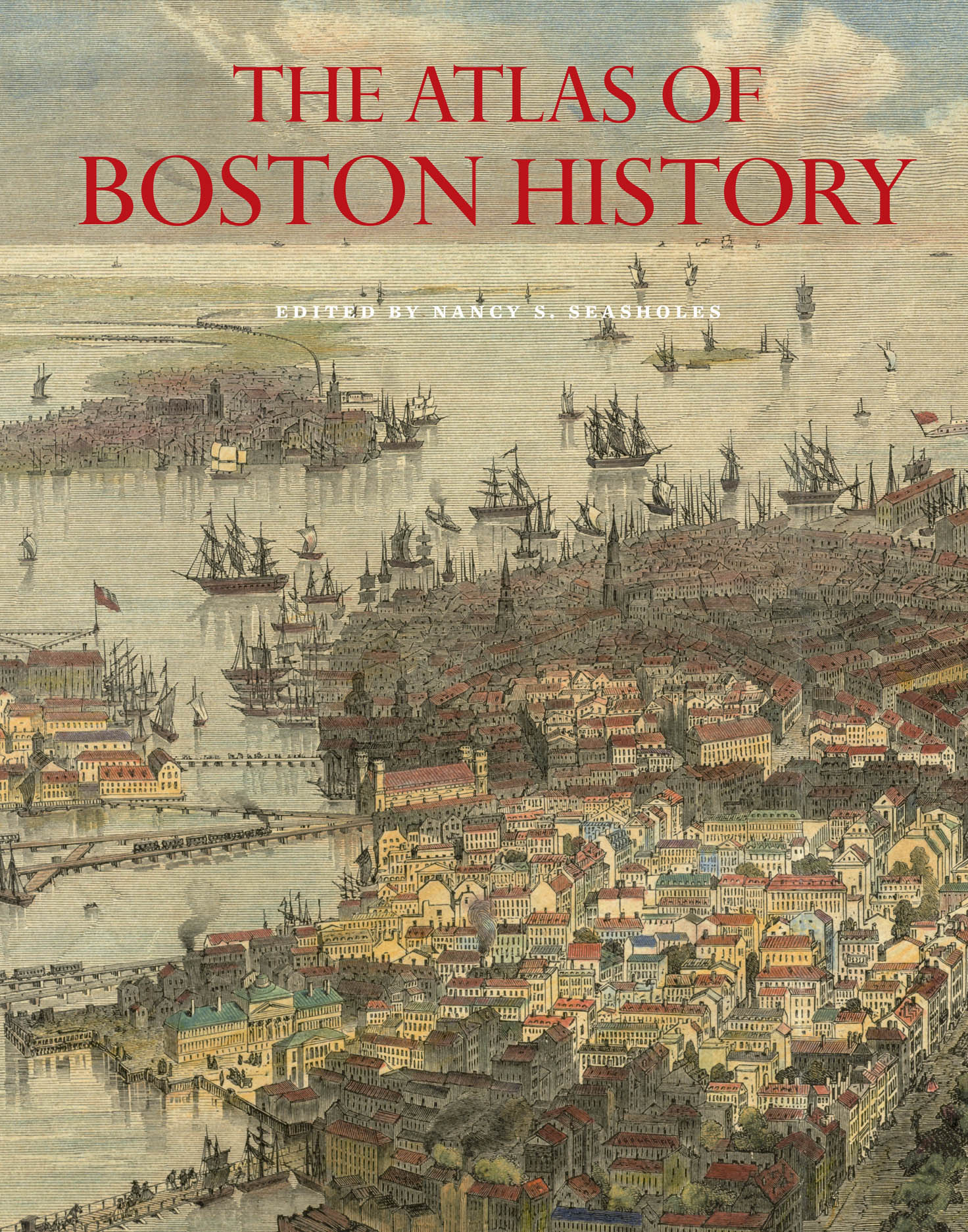

The Alarm Guns Will be Posted at the Artillery Barracks, the Common & the Lines, the Alarm given at either of those places, is to be repeated at all the rest, by firing three Rounds each.Bartons Point was the northwest tip of the town, sticking out into the Charles River. It’s striking that the army adopted the designation “Liberty Tree” for the big elm in the South End, despite its political origin.

On the Alarm being given the 52d Regt. is immediately to Reinforce the Lines, leaving a Captain & 50 at the Neck, The 5th Regt. will draw up between the Neck Guard & the Liberty Tree.

The 4th or Kings own Regt. will Reinforce the Magazine Guard with a Captain & 50 and with the Remainder draw up under Bartons Point.

The 43d Regt. will join the Marines & together defend the Passage between Bartons Point & Charles Town Ferry.

The 47th Regt. will draw up in Hanover Street securing both the Bridges over Mill Creek.

The 59th Regt. will draw up in the Front of the Court House.

The 3 Companies of the 18th Regt. joined by those of the 65th Regt. the 10th 23d & 38th Regts will draw up in the Street between the Generals House & Liberty Tree.

Majors [William] Martins Company of the Royal Regt. of Artillery will move with expedition to the Lines, Reinforcing the Neck with one Commission’d Officer 2 Non Commission’d & 12 Men the Remainder of the Royal Regt. of Artillery will get their Guns in order & wait for orders.

If any Alarm happens in the Night, the Troops will March to their Post without Loading, & on no Account to Load their Firelocks, it is forbid under the Severest Penalty to fire in the Night, even if the Troops should be fired upon, but they are to Oppose & Route any body that shall dare to Attack them (with their Bayonetts) And the greatest care will be taken that the Countersign is well known to all the Corps & Small Parties, Advanced, that in case of meeting they should know their friends & not Attack each other in the Night thro’ Mistake.

The Officers Commanding Regts will Reconoiter the Streets leading from their Quarters, to their Respective Alarm Posts. & fix upon the Streets they intend passing thro’, each taking a different Route.

Gen. Gage’s plan was never implemented, of course. On 20 Apr 1775, he stated: ”All former Orders Respecting Alarm Posts to be Cancel’d, & the Regts. to form in their Barracks.”