“Lt. Hawkshaw yesterday near expiring thro. his bad wounds”

As recorded by his regiment’s surgeon, blood gushed from his nose and mouth as well as his wound. Some of the affected tissue became inflamed. He had trouble swallowing.

People thought Lt. Hawkshaw was lying on his deathbed. And according to legal and popular understandings of the time, that meant he couldn’t lie in another way. After all, a person wouldn’t utter a falsehood just before meeting his maker, right?

Or, as a legal maxim quoted in 1700s reference books said: Nemo moriturus præsumitur mentiri. A dying person is not presumed to lie.

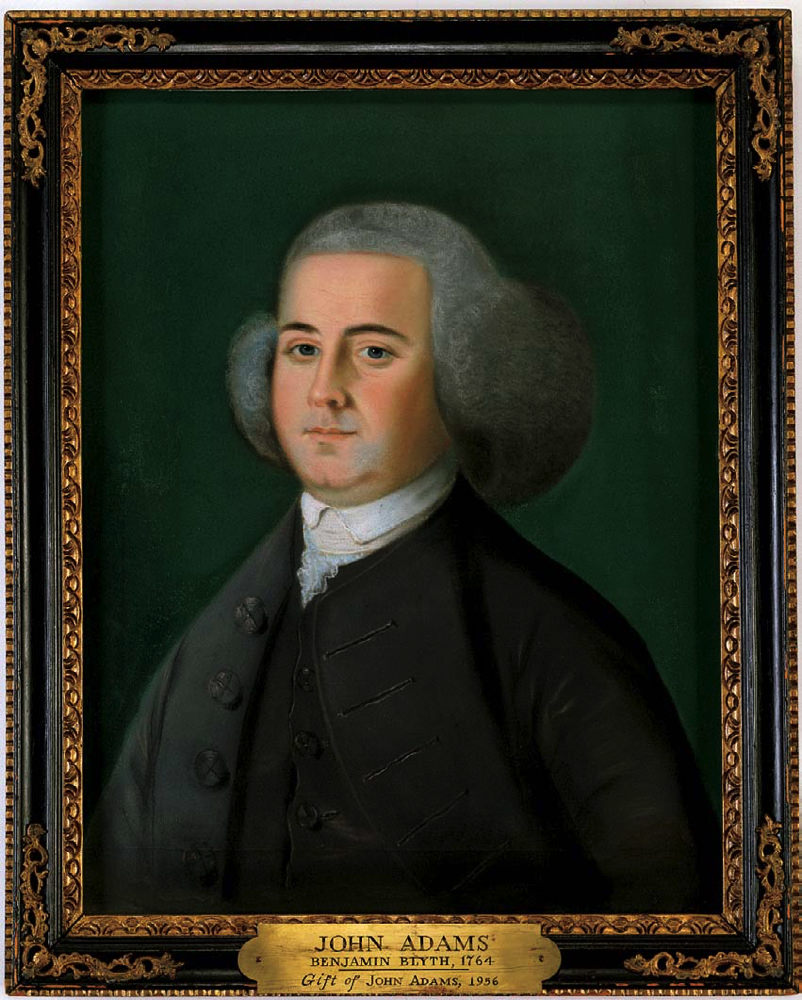

Usually that “dying declaration” doctrine allowed testimony from a dead victim that would otherwise be ruled out as hearsay. Thus, Patrick Carr’s doctors could report his remarks about the soldiers holding back before the Boston Massacre in 1770. To discredit such strong evidence, Samuel Adams had to resort to sneering that Carr “in all probability died in the faith of a roman catholick.”

The same thinking made “deathbed confessions” convincing. In the case of Lt. Hawkshaw, word went around that as his life slipped away he blamed the army for starting the war. Justice of the peace Edmund Quincy wrote to John Hancock on 22 April:

Here they say & swear to it all round, in excuse of ye Regulars, proceeding at Lexinton—that they were attack’d first & I doubt not many oaths of Officers & men are taken before J. G—ley [Justice Benjamin Gridley], to confirm it—but among others who contradict ’em—Lt. Hawkshaw yesterday near expiring thro. his bad wounds——Call’d Several Credible persons to him & told ’em as a dying man—that he was obliged in Conscience to confess—that the first Action of ye Whole at L. was done by the Kings troops—wr. they killd & wounded eight men—but doubtless you have sufficient proof of ye Fact & every Circumstance attending near at hand— . . .As discussed here, Quincy gave that letter to Dr. Benjamin Church, Jr., who slipped it to Gen. Thomas Gage. Which meant Lt. Hawkshaw’s commander read that he was contradicting the official army line.

Capt. [John] Erving, at his house yesterday Gave me ye Account of Hawkshaws Confesso.-proved to him at ye No: End yesterday to be real

TOMORROW: A quick response.