Here are answers from the start of the

second part of the Great 1770 Quiz.

VII. What were the real names of people in Boston behind these nicknames or pseudonyms used in 1770?

A) Determinatus

B) The Irish Infant

C) Michael Johnson

D) Paoli

E) Philanthrop

F) Shan-ap-Morgan

G) Vindex

H) William the Knave

One site to find almost all of these names is

Boston 1775. Use the search box in the upper left corner of the screen (on the desktop design). I’ve discussed everything but “Paoli.” Of course, one should still confirm what I’ve written, but this site offers a quick start.

Three of those names are pen names used in newspaper essays.

Samuel Adams wrote as “Determinatus” and “Vindex,” among many other pseudonyms.

Jonathan Sewall signed himself “Philanthrop.” Many newspaper readers knew the identities behind those signatures; they weren’t actually concealing much.

Two other nicknames are examples of how people attacked their political enemies in newspaper essays. Adams called

Customs Commissioner

John Robinson “Shan-ap-Morgan” because he came from Wales.

Boston Chronicle printer John Mein called

William Molineux “William the Knave,” along with my favorite, “Admiral Renegado.”

It’s not clear which category “Paoli” belongs in. In 1769 the unsuccessful Corsican revolutionary

Pasquale Paoli (1725-1807) was celebrated in Britain, where it was easier to cheer people rebelling against the

French king than rebelling against one’s own. American Whigs toasted Paoli,

Ebenezer Mackintosh named a child after him, and a Pennsylvania tavern with his name grew into a

township (and 1777 battle site).

In an 18 Feb 1770 letter

Thomas Hutchinson wrote about Molineux, “whom the Sons of Liberty have given the name of Paoli.” The

Censor magazine for 14 Mar 1772 likewise referred to “the

Bostonian who assumes the name of

Paoli.” But those are

Loyalist voices, not actually Molineux’s friends. In fact, they were his enemies, eager to make him seem conceited or alarming.

So did Molineux and his colleagues really use the nickname “Paoli” regularly and unironically? I’m not sure. But many historians have accepted Hutchinson as an accurate reporter and repeated that Molineux seized on the Corsican’s name.

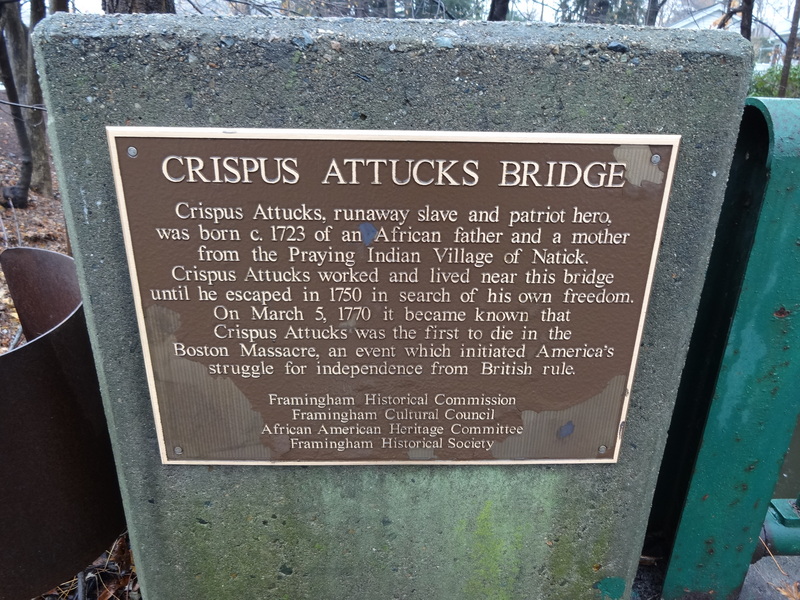

On to “Michael Johnson.” In the week after the

Boston Massacre, newspapers and coroners referred to one dead victim under that name. Then suddenly they started calling that tall mulatto man

Crispus Attucks—without, unfortunately, offering any explanation for the change. Most historians suspect Attucks was living under an alias, but that’s still a guess.

Finally, in his autobiography

John Adams recalled how the merchant

James Forrest, “then called the Irish Infant,” asked him to defend the

soldiers after the Massacre. Adams used the same nickname in an 1816 letter to

Jedidiah Morse. He described Forrest in tears, so people have interpreted the nickname to mean Forrest, an Irishman, cried as easily as a baby.

That said, I haven’t found any other source describing Forrest by that name or trait. When Forrest told the Loyalists Commission about the services he’d rendered to the Crown, he didn’t mention securing the soldiers’ defense attorney. And the

younger Abigail Adams used the phrase “the Irish infant” to describe a little person she saw in London in 1785. So there’s still a little mystery there.

Both

Kathy and

John matched all the nicknames to the right people.

VIII. After approving the Short Narrative of the Horrid Massacre, Boston voted to send a copy to about two dozen potentially sympathetic readers in Britain. Who was the only woman on that list?

Boston’s

Short Narrative report can be found at many websites, and in multiple editions. The first printing, as shown by the copy Molineux sent to

Robert Treat Paine and

the Massachusetts Historical Society later digitized, ends with an index of witnesses. The

town meeting authorized a

committee to send copies to “the Duke of Richmond, General [

Henry Seymour] Conway, and such other Gentlemen as they may think proper” in Britain.

On 16 May, the printers produced more copies with some new pages at the end listing the people in Britain that committee had chosen. A footnote explained, “This list and the following letter, are annexed to such copies only of this pamphlet, as are intended for publication in America.” Then more material was added for later printings. The longer copies were the basis of reprints in

1849 and

1870.

There’s one female name on that long list of recipients: the Whig historian

Catharine Macaulay (shown above during her 1784-1785 visit to the U.S. of A.).

Both

John and

Kathy identified that supporter of the American cause.

IX. What site on the Freedom Trail came under new management in 1770?

There are a limited number of sites on the Freedom Trail, some of which didn’t even exist in 1770. So that narrows down the possibilities.

The

Freedom Trail Foundation’s own webpage about those sites includes an entry that begins: “Built around 1680, the Paul Revere House, owned by the legendary patriot from 1770-1800…” A-ha!

A little research in biographies confirms that

Paul Revere bought the North End house now named after him in late 1770. It was his home and place of business for several years, though he moved out for grander quarters well before he sold it.

Both

Kathy and

John correctly landed on that site.

TOMORROW: Tar, feathers, and death.

_by_Robert_Edge_Pine.jpg/220px-Catharine_Macaulay_(n%C3%A9e_Sawbridge)_by_Robert_Edge_Pine.jpg)