Whose Handprint Is on the Declaration?

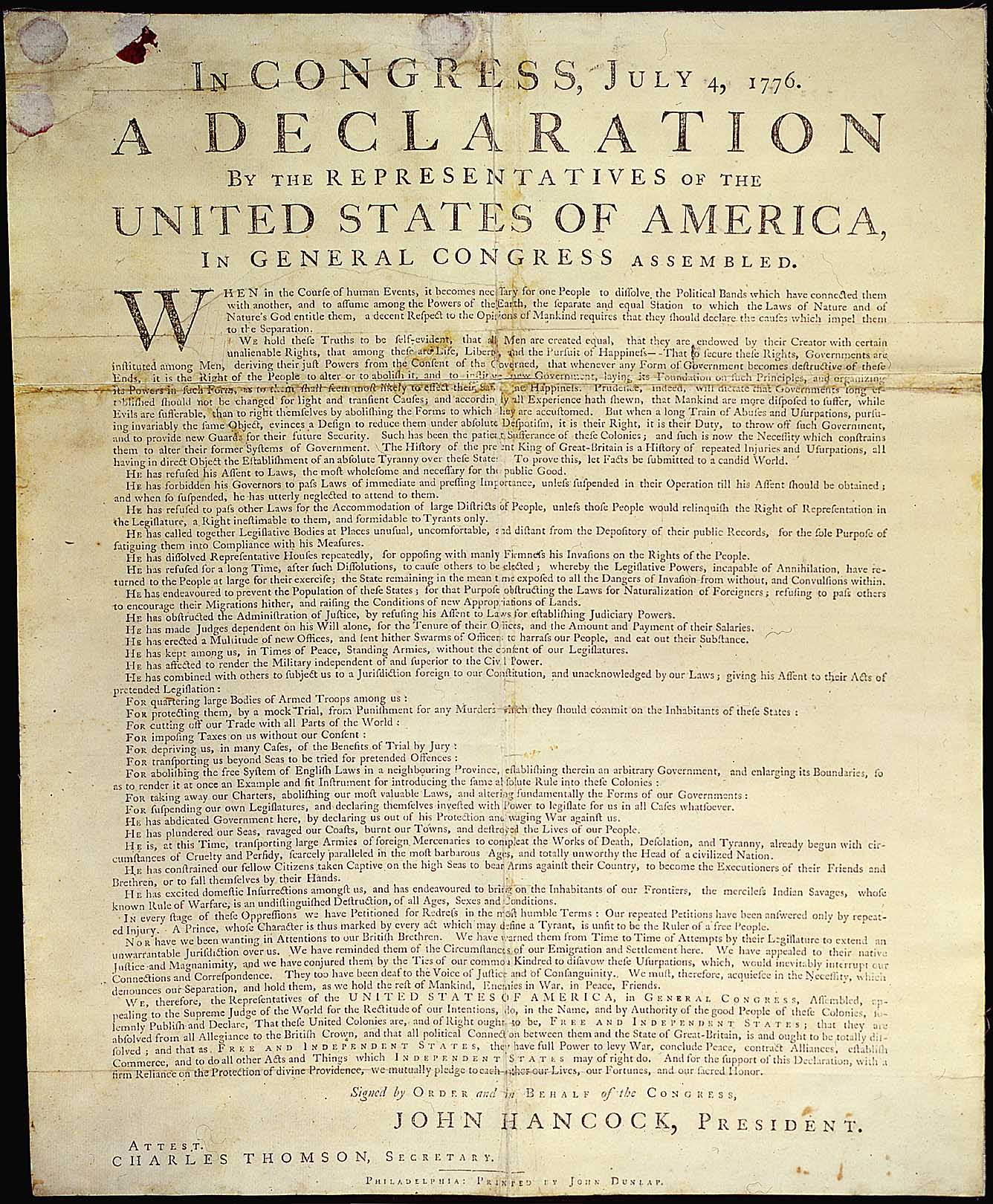

Fontana Micucci’s article at Boundary Stones focused my attention on something I’d seen for years without thinking about—there’s a handprint on the corner of the Declaration of Independence.

By “Declaration of Independence” in this case, I mean the engrossed copy written out by scribe Timothy Matlack in the summer of 1776.

(I think we’ve come to equate that physical document too closely with the Declaration and forget that for the first generations of Americans it was a set of words, not an object they ever saw, even in facsimile. The Declaration was originally a text, not a textile. But I digress.)

The National Archives, current custodian of the engrossed copy, has a detailed article on its preservation over the years. Perhaps because that agency was put in charge of the Declaration only after World War 2, it’s candid about earlier missteps.

I remember reading that the handwritten Declaration is so faded today because the first facsimiles of it, authorized in 1823 by John Quincy Adams as secretary of state, had been produced using a “wet transfer” process that removed some of the ink. With great irony, the reproductions that made that handwritten document into a national icon left the original permanently damaged. All legible copies of the Declaration today are actually reproductions of the early copperplate engraving because the original has faded so much.

The National Archives article upended my understanding a bit. While time and the wet transfer process did cause some fading in the Declaration’s first century, a series of photographs starting in 1883 shows that most of the damage to the words happened in the early 1900s.

A 1903 photo shows “a text that is completely legible and free of water stains.” And back then, there was no handprint.

The Library of Congress commissioned more photos in 1922, but those images can’t be located. The next surviving photographs therefore come from 1940.

By then, the Declaration had suffered noticeable damage in several areas. The ink was more faded. Some of the words no longer looked as crisp as they had four decades earlier. New marks on the parchment included the imprint of a left hand at lower left and water stains near the center.

Most significant, the National Archives article reports, “Some signatures, such as John Hancock’s, were enhanced while others were rewritten in efforts to make them more visible.” The H in Hancock was overwritten to be taller, for example.

People probably tried to clean or restore the Declaration in the early twentieth century, and that effort (or series of efforts) went awry. But evidently no U.S. government records survive to say when and how that happened. And the handprint, while obviously on the document today, isn’t clear enough to identify the responsible party.

By “Declaration of Independence” in this case, I mean the engrossed copy written out by scribe Timothy Matlack in the summer of 1776.

(I think we’ve come to equate that physical document too closely with the Declaration and forget that for the first generations of Americans it was a set of words, not an object they ever saw, even in facsimile. The Declaration was originally a text, not a textile. But I digress.)

The National Archives, current custodian of the engrossed copy, has a detailed article on its preservation over the years. Perhaps because that agency was put in charge of the Declaration only after World War 2, it’s candid about earlier missteps.

I remember reading that the handwritten Declaration is so faded today because the first facsimiles of it, authorized in 1823 by John Quincy Adams as secretary of state, had been produced using a “wet transfer” process that removed some of the ink. With great irony, the reproductions that made that handwritten document into a national icon left the original permanently damaged. All legible copies of the Declaration today are actually reproductions of the early copperplate engraving because the original has faded so much.

The National Archives article upended my understanding a bit. While time and the wet transfer process did cause some fading in the Declaration’s first century, a series of photographs starting in 1883 shows that most of the damage to the words happened in the early 1900s.

A 1903 photo shows “a text that is completely legible and free of water stains.” And back then, there was no handprint.

The Library of Congress commissioned more photos in 1922, but those images can’t be located. The next surviving photographs therefore come from 1940.

By then, the Declaration had suffered noticeable damage in several areas. The ink was more faded. Some of the words no longer looked as crisp as they had four decades earlier. New marks on the parchment included the imprint of a left hand at lower left and water stains near the center.

Most significant, the National Archives article reports, “Some signatures, such as John Hancock’s, were enhanced while others were rewritten in efforts to make them more visible.” The H in Hancock was overwritten to be taller, for example.

People probably tried to clean or restore the Declaration in the early twentieth century, and that effort (or series of efforts) went awry. But evidently no U.S. government records survive to say when and how that happened. And the handprint, while obviously on the document today, isn’t clear enough to identify the responsible party.