“Lodged in part pay for the said Cannon”

In September and October 1774, as I describe in The Road to Concord, Gen. Thomas Gage’s royal government and the Patriots in and around Boston engaged in an “arms race”: racing to grab every cannon and mortar they could.

The Crown took two small cannon from the Cambridge militia, the guns on Governor’s Island, and the stock of hardware merchant Joseph Scott.

In the same weeks, Patriots emptied the Charlestown battery, removed a “great gun” from along the Dorchester shore, and spirited four brass cannon out of the two gunhouses of the Boston militia train.

The Royal Navy spiked all the guns in the town’s North Battery, but locals said they would clear those. Someone tried to float a boat loaded with guns up the Charles River, but it got stuck on the dam that formed the Mill Pond and the navy seized it.

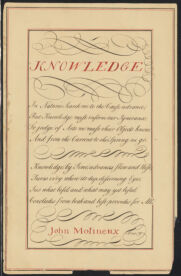

That was the period when the Boston Patriot firebrand William Molineux sent his son John to take four iron cannon out of a stable in West Boston owned by Duncan Ingraham, who a couple of years before had moved out to Concord with his new wife.

As I’ve been quoting, in 1791 Ingraham petitioned the Massachusetts General Court, of which he’d recently been a member, to compensate him for those cannon. He specified the amount this way:

Ingraham wrote that he hadn’t known about Molineux’s payment at the time, and perhaps not until shortly before his petition. That hints at a rift between the merchant captain and his namesake son. In 1774 they were on different political sides: Duncan, Jr., spoke for the Cadets in their dispute with Gen. Gage over having John Hancock as their colonel while Duncan, Sr., was considered a Tory by his Concord neighbors. The older man’s new wife might also have been an issue. Whatever the reason, his son didn’t tell him about making a deal with Molineux, perhaps for years.

Even after deducting that first payment, Ingraham asked Massachusetts for more than £82. In March 1792, the General Court voted to grant him only £58.13s.4d. Do the math, and the legislature’s committee decided that Ingraham’s four cannon were worth only £72.

The Crown took two small cannon from the Cambridge militia, the guns on Governor’s Island, and the stock of hardware merchant Joseph Scott.

In the same weeks, Patriots emptied the Charlestown battery, removed a “great gun” from along the Dorchester shore, and spirited four brass cannon out of the two gunhouses of the Boston militia train.

The Royal Navy spiked all the guns in the town’s North Battery, but locals said they would clear those. Someone tried to float a boat loaded with guns up the Charles River, but it got stuck on the dam that formed the Mill Pond and the navy seized it.

That was the period when the Boston Patriot firebrand William Molineux sent his son John to take four iron cannon out of a stable in West Boston owned by Duncan Ingraham, who a couple of years before had moved out to Concord with his new wife.

As I’ve been quoting, in 1791 Ingraham petitioned the Massachusetts General Court, of which he’d recently been a member, to compensate him for those cannon. He specified the amount this way:

Your Memorialist prays that he may be allowed for the aforesaid Cannon the aforesaid Sum of ninety six pounds, after deducting therefrom thirteen pounds six shillings & Eight pence which was lodged in part pay for the said Cannon at the Store of Duncan Ingraham Junr. as your memorialist has since been informed by said MollineuxSo William Molineux didn’t just take the guns; he left a down payment for them equal to a sixth of £80. (Where Molineux got his money and how much was actually his is a whole other question, linked to his sudden death on 22 October.) It’s not clear how Patriots slipped these weapons out of town, but they used various ways to smuggle military goods past the army guards on the Neck.

Ingraham wrote that he hadn’t known about Molineux’s payment at the time, and perhaps not until shortly before his petition. That hints at a rift between the merchant captain and his namesake son. In 1774 they were on different political sides: Duncan, Jr., spoke for the Cadets in their dispute with Gen. Gage over having John Hancock as their colonel while Duncan, Sr., was considered a Tory by his Concord neighbors. The older man’s new wife might also have been an issue. Whatever the reason, his son didn’t tell him about making a deal with Molineux, perhaps for years.

Even after deducting that first payment, Ingraham asked Massachusetts for more than £82. In March 1792, the General Court voted to grant him only £58.13s.4d. Do the math, and the legislature’s committee decided that Ingraham’s four cannon were worth only £72.