An Acquittal and a Conviction

The colonel was John Mansfield of Lynn, originally scheduled to be tried in early August. The major was Scarborough Gridley of Stoughton, in the artillery regiment. As I described yesterday, Gridley had stayed out of the main fighting at Bunker Hill and ordered Mansfield (who had a higher rank) to keep his infantry regiment nearby.

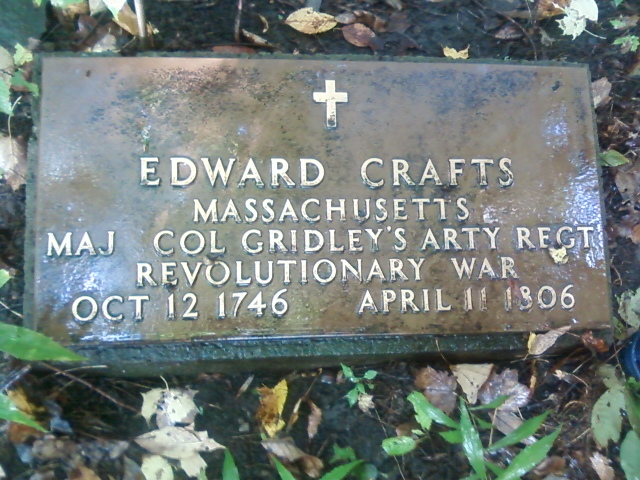

The captain was another artillery officer, Capt. Edward Crafts (1746-1806). He was a younger brother of Thomas Crafts, one of the Loyall Nine who organized the first public protest against the Stamp Act and then remained active in Whig politics. Thomas was an officer in Boston’s militia artillery company, and Edward trained in that unit as a young man.

Edward Crafts was a tinner by profession. He was still in Boston in 1770, when he supplied a deposition for the town’s Short Narrative of the Horrid Massacre. But back in 1768 he had married a country girl, Eliot Winship of Lexington. In 1771 the growing family moved to Worcester. At the end of 1773 Edward became a founding member of the American Political Society, his new town’s new club for Whig politics.

As the province moved toward military conflict in 1774, Worcester put Crafts on a committee to acquire and mount four cannon. He started to train a militia regiment to use those guns. Both Massachusetts Provincial Congress records and spy reports to Gen. Thomas Gage describe a large number of artillery pieces in the town by the spring of 1775.

When war broke out, however, Edward Crafts marched as a private in the town’s minuteman company. Then he returned home and recruited an artillery company to serve through the rest of the year. According to most listings of the Massachusetts artillery regiment under Col. Richard Gridley, Crafts was the senior captain.

That might have given him the stature, and the boldness, to challenge Maj. Scar Gridley. The colonel’s son was nominally fourth in command of the regiment, but in practice he was the colonel’s main aide and protégé. Sometime in the summer of 1775, after Maj. Gridley had behaved so ineffectually at Bunker Hill, he and Capt. Crafts exchanged words and accusations.

That led to the first of a series of court-martial proceedings, starting 1 September. The next day’s general orders announced the verdict:

Capt. Edward Crafts of Col. Gridley’s regiment of Artillery, tried yesterday by a General Court Martial, is acquitted of that part of the Charge against him, which relates to [“]defrauding of his men,” and the Court are also of opinion, that no part of the Charge against the prisoner is proved, except that of using abusive expressions to Major Gridley; which being a breach of the 49th Article of the Rules and Regulations for the Massachusetts Army; sentence the Prisoner to receive a severe reprimand from the Lt Col. of the Artillery in the presence of all the Officers of the regiment and that he at the said time, ask pardon of Major Gridley for the said abusive language.The lieutenant colonel of the regiment was William Burbeck. I have no idea if he made Capt. Crafts perform this ritual before the end of the month because there was still more legal business to get through.

According to the diary of Lt. Benjamin Crafts (an Essex County cousin of the Crafts brothers from Boston), Col. Mansfield’s court-martial started on 8 September. A week later, on 15 September, the commander’s general orders declared the outcome:

Col. John Mansfield of the 19th Regt of foot, tried at a General Court Martial, whereof Brigdr Genl [Nathanael] Green was president, for “remissness and backwardness in the execution of his duty, at the late engagement on Bunkers-hill”; The Court found the Prisoner guilty of the Charge and of a breach of the 49th Article of the rules and regulations of the Massachusetts Army and therefore sentence him to be cashiered and render’d unfit to serve in the Continental Army.Notably, although the Continental Army kicked Mansfield out, the voters of Lynn chose him for their town committee of correspondence, inspection, and safety almost every year until the end of the war, and also voted to have him moderate town meetings.

The General [Washington] approves the sentence and directs it to take place immediately.

Likewise, the voters of Newbury sent Samuel Gerrish to the Massachusetts General Court in 1776, the year after the army cashiered him the same way. Those gentlemen’s neighbors felt they still deserved leadership responsibilities.

COMING UP: The trial of Scarborough Gridley.

[The photo above shows the modern marker on Edward Crafts’s grave in Potter, New York, where the family moved in 1792, courtesy of Find a Grave. The original stone also survives there.]