The

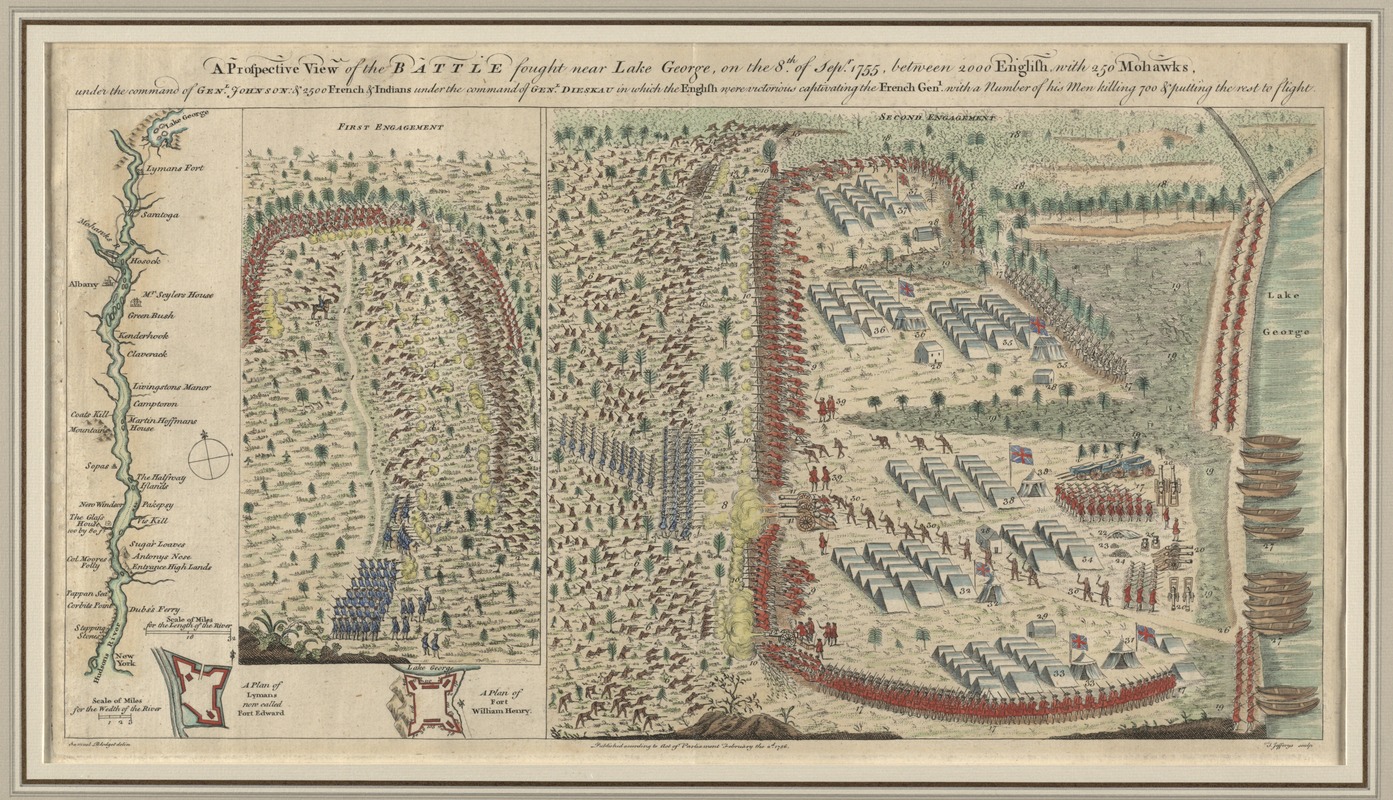

Battle of Lake George on 8 Sept 1755 probably involved fewer than 3,500 men, a little more on the British side than the

French. Each commander reported that his force had faced a much larger foe, however.

Each commander also reported inflicting more casualties than his force suffered, and more casualties than the rival commander reported. In fact, it seems impossible to pinpoint the number of dead and wounded.

Both sides lost leaders, however. On the French side,

Baron Dieskau was wounded and captured, and Canadian commandant

Jacques Legardeur de Saint-Pierre was killed. The British lost Col.

Ephraim Williams and Mohawk ally

Hendrick Theyanoguin. Among the provincial officers who died of their wounds was Capt.

William Maginnis of

New York.

Gen.

William Johnson was wounded early in the fighting near Lake George and had to sit out the rest of the battle. Not that he mentioned the last detail in his report to the Crown. Nor did he name Col.

Phineas Lyman as the officer who took over and completed that part of the fight. But of course Johnson portrayed the battle as a great victory for Britain.

It probably

was a British victory, though limited and costly. Crown forces could now move safely from Fort Lyman to Lake George, and the lakefront was clear enough to build another fort there.

But that clash was an even bigger win for William Johnson, Britain’s liaison to the

Iroquois and new provincial general. He was made a baronet, thus Sir William Johnson. Eventually

Benjamin West painted Johnson nobly sparing a French officer from attack by a Native warrior, as shown above.

The new baronet returned the king’s favor, renaming the nearby landmarks for the royal family: Lac du Saint-Sacrement became Lake George after

George II, Fort Lyman became Fort Edward after one of the king’s grandsons (another slight for Phineas Lyman), and the new fort was dubbed Fort William Henry after the king’s younger son and another grandson. Since the territory remained in British hands, those names prevail.

As the senior (and surviving) British captain in the last part of this battle,

Nathaniel Folsom enjoyed some of that glory. He rose within the

New Hampshire military establishment, ranked as a colonel within a couple of years. Folsom’s businesses in Exeter prospered.

In 1774 the province chose Nathaniel Folsom as a representative to the

First Continental Congress, alongside

John Sullivan. His son, Nathaniel, Jr., participated in the first raid on Fort William and Mary that December. Decades later a veteran named Gideon Lamson stated (using military titles the men acquired later):

At nine, Colonel [John] Langdon came to Stoodley’s and acquainted General Folsom and company with the success of the enterprise,—that General Sullivan was then passing up the river with the loaded boats of powder and cannon.

Folsom took charge of one barrel of gunpowder removed from the fort.

Given Nathaniel Folsom’s success in the last war, his support for the Patriot resistance, and his activity in the New Hampshire Provincial Congress, it’s no surprise that that body voted to make him commander of the province’s troops on 21 Apr 1775. The legislators reaffirmed that decision on 23 May.

The problem was that no one had checked with the officer who was actually leading the New Hampshire troops around Boston.

TOMORROW:

Stark divide.

_crop.jpg/250px-General_John_Stark_-_Ulysses_Tenney%2C_c1790_(Manchester_Hist_Assoc_MHA_316)_crop.jpg)