On the

list of political troublemakers in Boston published in the

New-York Gazetteer in September 1774, the last name is William Denning.

There was no one in Boston with that name. In their analysis of this list, Dan and Leslie Landrigan of the

New England Historical Society guessed that meant

William Denning (1740–1819), a

New York Whig who went on to serve one term in the U.S. House.

That makes no sense, or, as the Landrigans put it, “William Denning stands out” on a list of men from Boston because he

wasn’t from Boston.

I think whoever wrote the list must have been thinking of

William Dennie (1726–1783), a merchant whom the Boston Whigs pulled onto committees when they wanted more representation from the business community.

Writing in 1898, H. W. Small characterized Dennie as “a wealthy Scot.” His family roots were in Scotland, but Dennie was born in Fairfield,

Connecticut, the seventh child of a large established family.

Dennie was working as a merchant in Boston by his early twenties, according to a 1752

lawsuit against

William Vassall. In 1755 he joined many other businessmen in signing a petition to abate Boston’s taxes. In the next decade his shop was “at the lower End of King Street,” near the Long Wharf. Among many other goods he sold

tea, some shown by John W. Tyler as coming from

Holland. By 1771, the town tax list found he owned a house, a warehouse, one

slave, 280 tons of

shipping, and £1,500 worth of merchandise.

William’s older brother John Dennie was also a prominent Boston merchant in the 1750s, building an estate in the part of

Cambridge that became Brighton. He went bankrupt in the wake of

Nathaniel Wheelwright’s default in early 1765. Politically, John Dennie was a

Loyalist; he remained in Massachusetts but died in 1777.

John and William’s brother Joseph Dennie also came to live in Boston. He married into the Green family who staffed many American

print shops and the Boston

Customs office. He went

insane around 1776. Joseph’s

namesake son worked in

James Swan’s mercantile house as a teenager before becoming one of the early republic’s leading essayists.

Another of William Dennie’s nephews was

William Hooper, who moved to North Carolina and represented that colony at the

Continental Congress, signing the

Declaration of Independence.

Unlike

William Molineux,

John Bradford, and

Nathaniel Barber, three other businessmen on the 1774 list, Dennie was not prominent at many Boston protests. He was more the type to sign petitions and join clubs.

In fact, in 1768 Dennie declined to sign the town’s first

non-importation agreement to oppose the

Townshend duties. By early 1770, however, the Whigs had won him over, and he served on committees to remonstrate with the remaining holdouts, particularly the

Hutchinson brothers.

In November 1772 Dennie agreed to be part of Boston’s new committee of correspondence while other prominent merchants, including

John Hancock and

Thomas Cushing, declined.

On 27 May 1774,

John Rowe wrote in his diary that Dennie was one of the loudest voices booing the Customs Commissioners when they gathered for a dinner, along with Molineux and

Paul Revere. Later that year Dennie was one of Molineux’s pallbearers.

That was as radical as Dennie got, it appears. He didn’t become part of the large committee to enforce the First Continental Congress’s boycott of goods from Britain. In August 1776 he begged out of serving on Boston’s wartime committee of safety. Three years later he was criticized for charging too much for duck cloth and tea, and had to go before a town committee and promise not to do that again.

William Dennie never married. According to

John Mein, he “kept Mr. Barnabas Clark’s Wife [Hepzibah] many years. & employs her Husband abroad while he is getting

Children for him at home.” The 1771 tax list does say Dennie was hosting Barnabas Clark (1722–1772) at his house. He later employed the Clarks’ son Samuel as a shipmaster.

In 1773 there was a dispute in

Barnstable over whether that town should appoint a committee of correspondence to communicate with Boston’s.

Joseph Otis recalled that a neighbor named Edward Bacon objected to the character of the Boston committee men, specifically

Mr. Mollineaux Mr. Dennie & Dr. [Thomas] Young as men of very bad Characters (as near as I can Remember), Intimating one was an Atheist, one Never Went to Meeting, and the Other was Incontinent

Molineux and Young were known for their

religious skepticism, which leaves Dennie as “Incontinent”;

Dr. Samuel Johnson defined that word as meaning “Unchaste; indulging unlawful pleasure.”

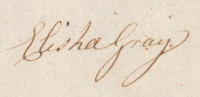

When Dennie died in 1783, he left legacies to many relatives, but the biggest bequest was to Hepzibah Swan (1757–1825, shown above), wife of James Swan, his executor. She was also the daughter of Barnabas and Hepzibah Clark.