The Mystery of “Mr. Swift from the North”

In the early twentieth century American historians did a lot of debunking. The Colonial Revival period had brought a lot of dramatic stories and traditions into print. Taking a more evidence-based approach, the next generations of authors lopped away at myths and hagiography.

The dramatic story of Samuel Swift’s martyrdom—coming from his family, unsupported by other evidence, incredible in its details—was the sort of lore that debunking authors tried to clear out of reliable histories.

But Samuel Swift’s reputation as a strong Patriot survived into the mid-1900s.

That’s because of a conjunction of sources. First, back on 7 Nov 1765 the Boston News-Letter reported about that year’s tightly controlled 5th of November celebration:

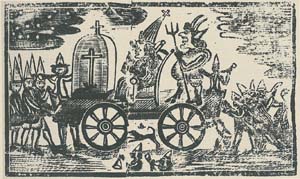

The Leaders, Mr. McIntosh from the South, and Mr. Swift from the North, appeared in Military Habits, with small Canes resting on their Left Arms…(Pierre Eugène du Simitière’s sketch of leaders of the 1767 Pope Night parades, with canes and speaking trumpets, appears above.)

In the nineteenth century the authors Caleb Snow, Samuel A. Drake, and Francis S. Drake reprinted or paraphrased that 1765 news story, including the name “Swift.”

In 1891, the editors of the Jeremy Belknap Papers from the Massachusetts Historical Society identified Samuel Swift as “one of the Committee of Safety, and a prominent man at the North End.”

The “Committee of Safety” reference probably derives from a line in Samuel Swift’s 2 Oct 1774 letter to John Adams: “The Committee of Safety by me pay their best Regards to you.” But there was no formal “committee of safety” at the time. The town of Boston hadn’t named Swift to its committee of correspondence. He wouldn’t even be on the larger committee named on 7 December to enforce the Continental Congress’s Association boycott. It appears Swift was passing on regards from other men.

As for being “a prominent man at the North End,” Swift wasn’t a member of the North End Caucus. He didn’t hold high political office or militia rank. He was a justice of the peace from 1741 to 1760, but wasn’t reappointed under George III. As an attorney, Swift wasn’t a big employer, like shipyard owner John Ruddock.

I suspect the mention of “Mr. Swift from the North” in the 1765 newspapers caused those Belknap editors to identify that leader of the North End gang as Samuel Swift, thus making him “a prominent man” in that neighborhood.

Certainly that’s where George P. Anderson stood when he presented his ground-breaking paper “Ebenezer Mackintosh: Stamp Act Rioter and Patriot” to the Colonial Society of Massachusetts in 1924:

The leaders—Mackintosh of the South End and Samuel Swift of the North End—appeared in military habits, with small canes resting on their left arms, having music in front and at flank.For decades after that, historians identified Samuel Swift as the leader of the North End gang. After all, well respected scholarly sources said so.

But that never made sense. The Pope Night gangs were composed of young men and older boys from the working classes. Samuel Swift, a genteel fifty-year-old lawyer in 1765, was the sort of man they begged money from, not the sort to lead their raucous street processions.

In The Boston Massacre (1970), Hiller B. Zobel noted that Samuel Swift didn’t even live in the North End. The Thwing database shows he owned a house on Pleasant Street in the South End.

But among the people indicted for rioting after the 1764 Pope Night disturbances, Zobel reported, was a teen-aged shipwright named Henry Swift. Following his lead, many authors since 1970 have identified Henry Swift as the North End captain.

References to Samuel Swift as a politically active North End leader survive, however, including in the footnotes of older volumes digitized at Founders Online. He was an interesting character, but he wasn’t a militant in either 1765 or 1775.