As I quoted yesterday,

Isaiah Thomas grew up as an apprentice

printer hearing stories about how his master,

Zechariah Fowle, had helped to secretly print a New Testament in the late 1740s.

Thomas also heard about a complete Bible completed by another Boston printing partnership, also surreptitiously, by 1752.

However, it’s worth noting that in his

History of Printing in America (1810), Thomas admitted about the New Testament publication, “I have heard that the fact has been disputed.” While he claimed

John Hancock had owned a copy of the full Bible, he couldn’t point to any extant examples or describe how they might be recognized.

Indeed, in 1770 another Boston printer publicly denied the existence of any previous American-made Bible. The 3 Dec 1770

Boston Evening-Post included a large advertisement that began:

The First BIBLE ever printed in America.

PROPOSALS

For printing by Subscription, in a most beautiful and elegant Manner, in two large Volumes Folio.

The HOLY BIBLE,

Containing the OLD and NEW TESTAMENTS,

Or a FAMILY BIBLE,

With Annotations and Parallel Scriptures.

By the late Rev. SAMUEL CLARK, A.M.

The following paragraphs promised large and elegant type and

paper manufactured in America—or “superfine Imperial Paper” for those few ready to pay double for extra quality. The book was to be delivered in seventy installments of five pages each, starting two weeks after three hundred people had subscribed.

The printer making this offer was

John Fleeming, late of the

Boston Chronicle, now working out of “his PRINTING OFFICE, in

Newbury-street, nearly opposite the WHITE-HORSE Tavern,

Boston.” He had

married Alice Church in August and was probably looking for a way to support a family.

The annotator

Samuel Clarke (1626-1701) had been a Nonconformist minister in Britain who first published his edition of the Bible in 1690. That book was reprinted in Glasgow in 1765, which is probably how Fleeming, a Scotsman, got the text. The Rev.

George Whitefield praised Clarke’s work, and of course Americans widely admired Whitefield. Indeed, almost half of Fleeming’s advertisement was a quotation from Whitefield.

Within the next two months, the same ad appeared in many other New England newspapers and in

New York. However, Fleeming must not have collected the subscriptions he hoped for. In modern terms, his Kickstarter campaign failed. That edition was never published.

In 1782 the Philadelphia printer

Robert Aitken likewise announced that he would print the first English Bible in America. And he actually completed the job that September. The

Continental Congress and

George Washington both praised the enterprise. Many copies survive.

Obviously Fleeming and Aitken didn’t acknowledge the editions that Isaiah Thomas had heard about. Thomas would have said that was because the Kneeland and Green Bible, and the Rogers and Fowle New Testament that preceded it, had been disguised as London publications in order to get around a special grant to certain British printers.

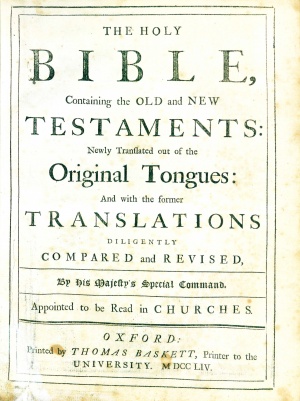

In different writings Thomas specified that the Boston Bible appeared in 1749 and carried the imprint “London: Printed by Mark Baskett, Printer to the King’s Most Excellent Majesty”—but that man didn’t start publishing Bibles until the 1760s. Was this a mistake for Thomas Baskett, who did issue Bibles in the 1740s? Or is its main significance as evidence that Thomas hadn’t actually seen the Bible he believed did exist?

Many book collectors have searched for the fake Baskett Bible that was actually printed in Boston. Presumably this means finding a Bible with a London Baskett imprint but with typography that didn’t match copies known in Britain.

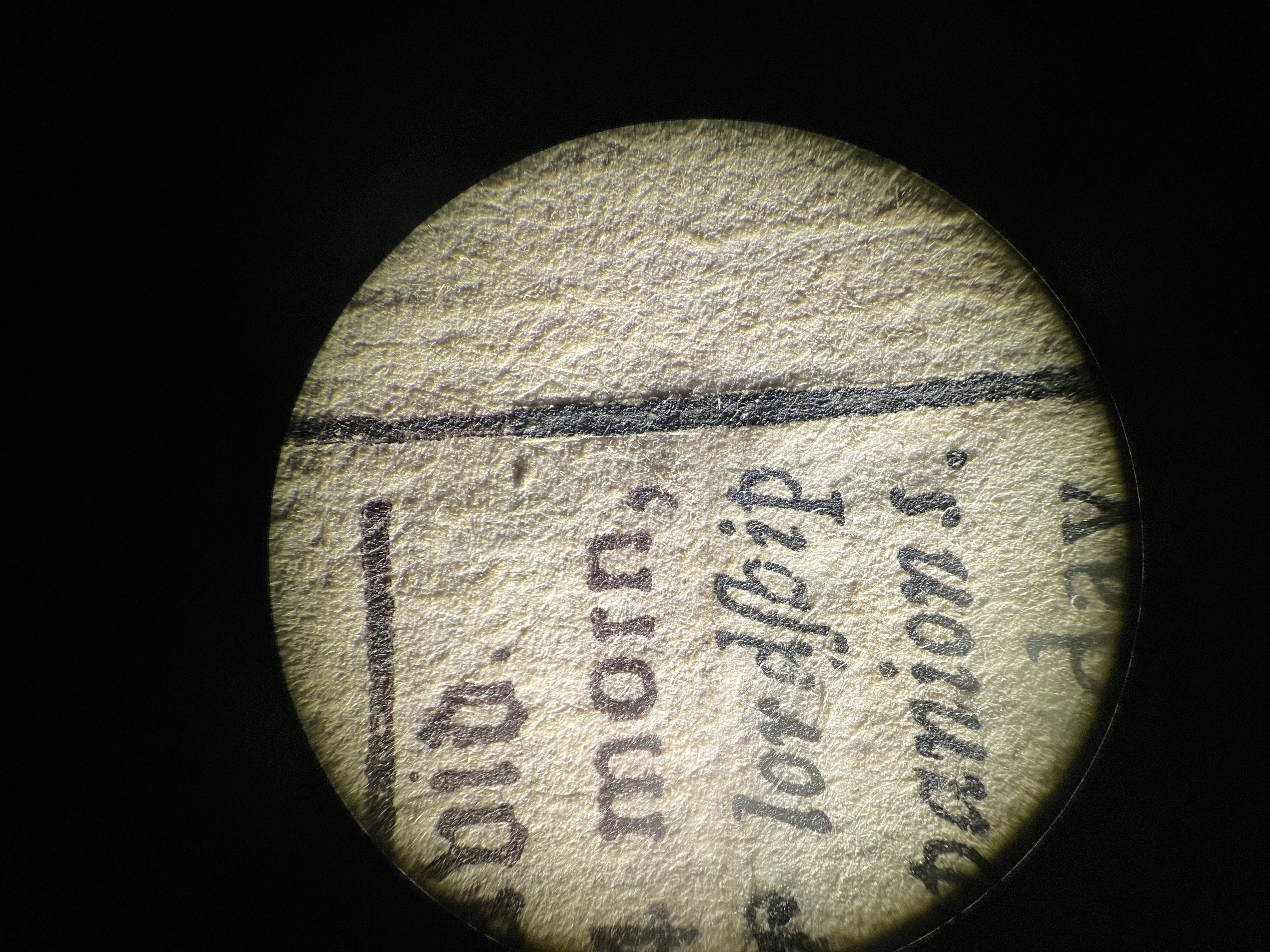

However, only one candidate for such a book has been found, surfacing in 1895, according to an article in the

Boston Globe. Three decades later, Dr. Charles L. Nichols’s close examination showed that was actually a genuine Baskett Bible from 1763 that someone had altered by removing one volume’s title page and clumsily changing the date on the other to 1752. See his

findings delivered to the Colonial Society of Massachusetts.

Nonetheless, as Nichols stated in a follow-up paper for the American Antiquarian Society (

P.D.F. download), he remained convinced that there was a Bible published surreptitiously in Boston, even if Thomas didn’t have all the details right.

Subsequent scholars, including

Randolph C. Adams in The Colophon in 1935 and

Harry Miller Lydenberg in the Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America in 1954, were more skeptical. They concluded that Thomas’s report was simply wrong.

Perhaps the digitization of books will produce the anomalous copy of a Baskett Bible that collectors have sought. More likely, however, Zechariah Fowle just lied to little Isaiah about how he’d labored long and hard over a secret publication of the Bible.