The Last Years of Baron de Steuben

Those were three of his former military aides: Benjamin Walker, James Fairlie, and William North. In the mid-1780s they all got married and set up their own households. That left the baron at loose ends in New York, living beyond his means.

Steuben enjoyed the company of young men—but not all young men. Sometime during the 1780s two nephews visited Steuben from Prussia. The baron quickly came to dislike them, especially because they expected him to provide their fare and living expenses (after all, he had written letters boasting of his success in America). They went home.

In the late 1780s the baron showered gifts on his butler, who North thought was a “worthless rascal” being dressed up as a “beau.” For a while in 1791 Steuben lived at Walker’s house.

In the spring of 1792, however, the baron set up a household at 32 Broadway and collected a new pair of companions. The first was John W. Mulligan (1774-1862), son of New York tailor and wartime spy Hercules Mulligan. A recent Columbia graduate, Mulligan started to study the law in the office of Alexander Hamilton but then took the job of Baron de Steuben’s secretary.

The next arrival was Charles Adams (1770-1800), son of John and Abigail Adams, another aspiring attorney. In April 1792, Adams told his mother about Steuben: “He is the best man in the world I sincerely beleive.” In a letter dated 8 Oct 1792, Charles Adams described how the baron had invited him to move in:

The Baron returned from Steuben [his town in upstate New York] last week and I had intended to procure lodgings at some private boarding house, but when I mentioned to him my intention, he took me kindly by the hand “My dear Adams said he When your sister went from New York I invited you to come to my house, at least till you could find more convenient and pleasant Lodgings; I then had not the pleasure of a long acquaintance with you, but I was pleased that in our little society we could be of mutual advantage to each other, and that our improvements in the French language and in other branches of literature would render my table the seat of improvement and pleasure.On 31 Jan 1793 Adams wrote to his father:

[“]I have since you have been here formed a very great and sincere friendship for you. You must now allow me the right of friendship; Indeed you must not leave me. What is it? Is there any thing you do not like? Is any thing inconvenient? I wish I could give you a better apartment, but the house will not aford it.[”]

I told him there was not a desire I could form but what was accomplished in his house; but that I did not think it proper that I should any longer take advantage of a kindness I had not a right to expect.

[“]And will you not then allow me to be any longer your friend and patron? You must not make such objections. It is not from any favor I can ever expect from your father. I am not rich, nor am I poor: and thank God I have enough to live well and comfortably upon; your being here does not make any difference in my expences. I love you, and will never consent that our little society should be broken, untill you give me more sufficient reasons for it.[”]

To this affectionate and fatherly address, I could only reply that I would do any thing he wished and would not leave him if he was opposed to my doing so. My dear Mamma there is something in this man that is more than mortal.

The Baron returned [from Philadelphia] on teusday his visit has been of service to him He said to me upon sitting down to supper that evening “I thank God my dear Charles that I am not a Great man and that I am once more permitted to set down at my little round table with Mulligan and yourself enjoy more real satisfaction than the pomp of this world can afford.”However, that situation was financially unsustainable. Steuben decided to move to his country estate, where life was cheaper. He headed out there in May 1793 and again in the spring of 1794. Vice President Adams understood the baron intended “there to reside for the Remainder of his Days.” Mulligan moved with him, still in the role of secretary.

On 12 Feb 1794, before leaving the city, Baron de Steuben made his third and final will (P.D.F. download). He had decided to “exclude my relations in Europe”—those nephews. Instead, he would “adopt my Friends and former Aid Des Camps Benjamin Walker and William North as my Children and make them sole devisees of all my Estates therein.” So they shared a financial inheritance which they probably would have had to sort out anyway.

Steuben left swords and other specific bequests to North and Walker. He left Mulligan “the whole of my library Maps and Charts and the sum of Two Thousand five hundred Dollars to complete it.” He assigned a year’s wages and clothes to his servants. Charles Adams, who was staying in the city to study for the bar, was a witness to the will. Another was Charles Williamson (1758-1808), a former British army officer who emigrated to America to promote land investments and the interests of the British Empire.

On 22 September, Charles Adams wrote to his mother:

On the fourteenth of October I shall set out for Albany The earnest solicitations of the Baron have drawn a promise from me to spend a few days with him at his solitude after I have passed my Counsellors examination. I have always lamented that you have so little acquaintance with this excellent man I never have know a more noble character and his affection for me calls forth every sentiment of gratitude which can exist in my breast.In November Adams’s father happily reported that Charles was “at Steuben after an Examination at Albany and an honourable Admission to the Rank of Counciller at Law.” But out on the baron’s estate, things were going poorly.

Early in the morning of 26 November, the general suffered a stroke. A biographer who relied on Mulligan’s memories wrote that a servant came to fetch him from another building:

Mulligan at once ran through the snow to his room, and found him in agony. Steuben appeared to have suffered much, and could only articulate a few words, “Do n’t be alarmed, my son,” which were his last.This account didn’t mention Charles Adams, but he must have been in the area because he wrote to his father (in a letter that no longer exists) that Steuben had suffered a “Palsy.” William North hurried over from his home in Duanesburg, and a doctor arrived.

But Steuben never regained consciousness. He died on 28 Nov 1794. Mulligan and North picked out his burial place “an eighth of a mile north of the house, on a hill in the midst of a wood.” Ten years later the baron’s remains were moved to the present gravesite.

Charles Adams married in 1795 but died only five years later, having drunk himself to death. John W. Mulligan around the same time wed a woman from Kentucky; they had nine children. He lived until 1862, thus witnessing the end of the Revolutionary War and the start of the Civil War.

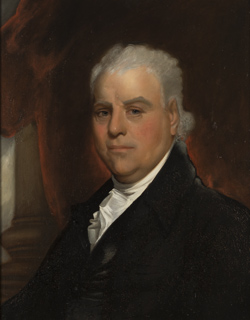

[The statuary shown above, labeled “Military Instruction,” consists of an ancient warrior displaying a sword perilously close to a nearly naked young man. It’s part of the monument to Steuben in Lafayette Park, Washington, D.C. The baron would have loved it.]