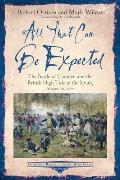

A Print of a “Patriotick Barber”

As I discussed back here, that was one of several images Sayer, Bennett, and probably Dawe produced for British customers interested in American affairs.

The artist appears to have taken inspiration from news stories printed in British newspapers. In this case, the article appeared in the 7 January Kentish Gazette, the 13 January Edinburgh Advertiser, and perhaps elsewhere.

As quoted by R. T. H. Haley in The Boston Port Bill as Pictured by a Contemporary London Cartoonist, it said:

The following card, copies of which were circulated at New York, is too singular not to merit insertion:The picture showed the barber, well wigged but ugly and sneering, pushing the handsome but half-shaved captain out of his chair. “Orders of Government” poke from the captain’s pocket while another man tries to hand him a letter marked “To Capt. Crozer.”

“A Card,

“New York, Oct. 3rd.

“The thanks of the worthy sons of liberty in solemn Congress assembled, were this night voted and unanimously allowed to be justly due to Mr. Jacob Vredenburgh, Barber, for his firm spirited and patriotic conduct, in refusing to complete an operation, vulgarly called Shaving, which he had begun on the face of Captain John Crozer, Commander of the Empress of Russia, one of his Majesty’s [troop] transports, now lying in the river, but most fortunately and providentially was informed of the identity of the gentleman’s person, when he had about half finished the job.

“It is most devoutly to be wished that all Gentlemen of the Razor will follow this wise, prudent, interesting and praiseworthy example, so steadily, that every person who pays due allegiance to his Majesty, and wishes Peace, Happiness, and Unanimity to the Colonies, may have his beard grow as long as ever was King Nebuchadnezzar’s.”

The print carried the subtitle “The Captain in the Suds,” and underneath it was the verse:

Then Patriot grand, maintain thy Stand,On the barbershop wall are engraved portraits of the Earls of Camden and Chatham, British politicians who spoke up for the colonies’ cause, plus Chatham’s recent speech. Beside them hangs the Continental Congress’s Articles of Association, a boycott that hadn’t actually been announced when this incident took place.

And whilst thou sav’st Americ’s Land,

Preserve the Golden Rule;

Forbid the Captains there to roam,

Half shave them first, then send ’em home,

Objects of ridicule.

In the top and bottom of the picture are wig boxes with the names of local Whigs: “Alexander McDugell,” John Lamb, Isaac Sears, and so on. One says, “Welle Franklin.” Was that the royal governor of New Jersey?

Perhaps the most striking detail of this print is that I can’t find any mention of the incident in the American press, nor of the men involved. The event appears to have been recorded only in the British newspaper reports, and those would have been long forgotten if not for this picture.

But because the print was so dramatic, 200 years after publication it inspired Ashley Vernon and Greta Hartwig to create a one-act opera, The Barber of New York.

TOMORROW: More about the barber.