“A sotish, stupid, stubborn, worthless, brutish man”

That was not a good time for the Continental Army.

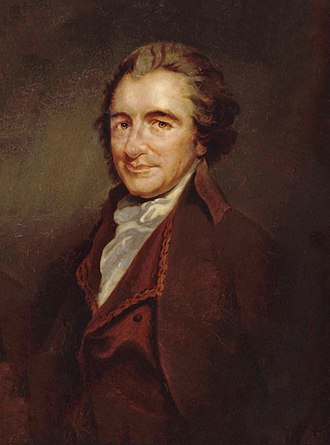

Returning to Philadelphia, Paine started to publish The Crisis, urging Americans not to let themselves fall back under the control of a tyrant:

Let them call me rebel, and welcome, I feel no concern from it; but I should suffer the misery of devils, were I to make a whore of my soul by swearing allegiance to one whose character is that of a sotish, stupid, stubborn, worthless, brutish man.In that quotation I followed the spelling and punctuation of the broadside issued “opposite the Court-House, Queen Street,” in Boston. That was how Edward Eveleth Powars and Nathaniel Willis, publishers of the Independent Chronicle, described their print shop, in a space originally used by James Franklin. The town hadn’t yet gotten around to giving the street a new, non-monarchical name.

I conceive likewise a horrid idea in receiving mercy from a being, who at the last day shall be shrieking to the rocks and mountains to cover him, and fleeing with terror from the orphan, the widow and the slain of America.

There are cases which cannot be overdone by language, and this is one. There are persons, too, who see not the full extent of the evil which threatens them; they solace themselves with hopes that the enemy, if he succeed, will be merciful.

It is the madness of folly, to expect mercy from those who have refused to do justice; and even mercy, where conquest is the object, is only a trick of war: The cunning of the fox is as murderous as the violence of the wolfe, and we ought to guard equally against both.