“I saw your Street door vomit forth a Crowd of Senators”

But it wasn’t clear what the legislature could do about that.

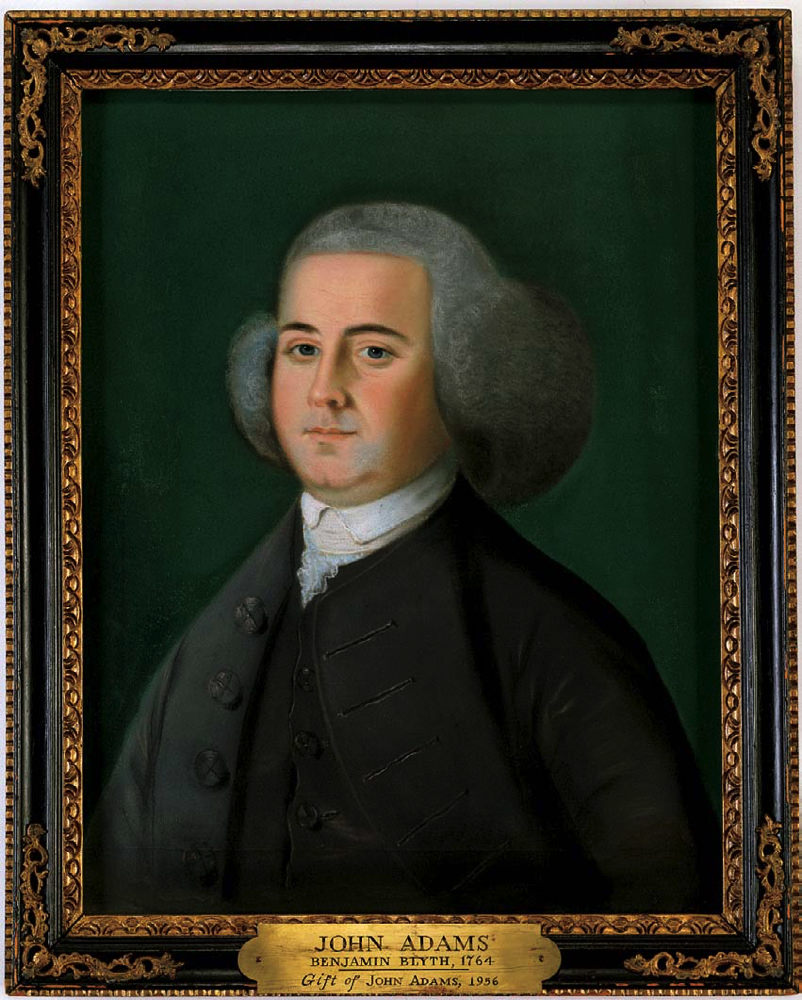

Until the lawyer John Adams had a bright idea. Or at least that’s how he described the situation in his post-presidential memoir. And in this case he may well be accurate.

According to the older Adams, he was motivated by fear of popular violence:

I fully expected that if no Expedient could be suggested, that the Judges would be obliged to go where Secretary [Andrew] Oliver had gone to Liberty Tree [in 1765], and compelled to take an Oath to renounce the Royal Salaries. Some of these Judges were men of Resolution and the Chief Justice in particular, piqued himself so much upon it and had so often gloried in it on the Bench, that I shuddered at the expectation that the Mob might put on him a Coat of Tar and Feathers, if not put him to death.Adams had served one term in the General Court in 1770–71, representing Boston, and then retired to Braintree for a while. In 1773 he was splitting his time between the towns and edging back into politics.

Adams recalled:

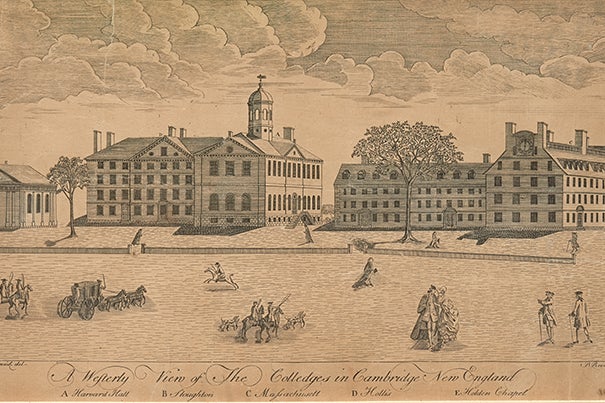

I happened to dine with Mr. Samuel Winthrop at New Bost[on], who was then Clerk of the Superiour Court, in company with several Members of the General Court of both Houses and with several other Gentlemen of the Town. Dr. John Winthrop Phylosophical Professor at [Harvard] Colledge and Dr. [Samuel] Cooper of Boston both of them very much my Friends, were of the Company.No one mentioned the Massachusetts legislature’s attempt in 1706 to impeach some associates of Gov. Joseph Dudley, squelched by the privy council in London. But of course any good lawyer could argue the differences between the cases meant that precedent didn’t apply.

The Conversation turned wholly on the Topic of the Day—the Case of the Judges. All agreed that it was a fatal Measure and would be the Ruin of the Liberties of the Country: But what was the Remedy? It seemed to be a measure that would execute itself. There was no imaginable Way of resisting or eluding it. There was lamentation and mourning enough: but no light and no hope. The Storm was terrible and no blue Sky to be discovered.

I had been entirely silent, and in the midst of all this gloom, Dr. Winthrop, addressing himself to me, said Mr. Adams We have not heard your Sentiments on this Subject, how do you consider it? . . . What can be done?

I answered, that I knew not whether any one would approve of my Opinion but I believed there was one constitutional Resource, but I knew not whether it would be possible to persuade the proper Authority to have recourse to it.

Several Voices at once cryed out, a constitutional Resource! what can it be?

I said it was nothing more nor less than an Impeachment of the Judges by the House of Representatives before the Council.

An Impeachment! Why such a thing is without Precedent.

I believed it was, in this Province: but there had been precedents enough, and by much too many in England: It was a dangerous Experiment at all times: but it was essential to the preservation of the Constitution in some Cases, that could be reached by no other Power, but that of Impeachment.

Adams continued in a common vein for him, saying that even his learned colleagues told him he was wrong, but he showed them he was right:

The next day, I believe, Major [Joseph] Hawley came to my House and told me, he heard I had broached a strange Doctrine. He hardly knew what an Impeachment was, he had never read any one and never had thought on the Subject. I told him he might read as many of them as he pleased. There stood the State Tryals on the Shelf which were full of them, of all sorts good and bad. I shewed him Seldens Works in which is a Treatise on Judicature in Parliament, and gave it him to read. . . . We looked into the Charter together, and after a long conversation and a considerable Research he said he knew not how to get rid of it.Benjamin Gridley was a fellow lawyer, but one who leaned toward the Crown and later became a Loyalist.

In a Day or two another Lawyer in the House came to me, full of doubts and difficulties, He said he heard I had shown Major Hawley some Books relative to the Subject and desired to see them. I shewed them to him and made nearly the same comment upon them. It soon became the common Topick and research of the Bar. . . .

The Members of the House, becoming soon convinced that there was something for them to do, appointed a Committee to draw up Articles of Impeachment against the Chief Justice Oliver. Major Hawley who was one of this Committee, would do nothing without me, and insisted on bringing them to my house, to examine and discuss the Articles paragraph by Paragraph, which was readily consented to by the Committee. Several Evenings were spent in my Office, upon this Business, till very late at night. One Morning, meeting Ben. Gridley, he said to me Brother Adams you keep late Hours at your House: as I passed it last night long after midnight, I saw your Street door vomit forth a Crowd of Senators.

TOMORROW: Putting the plan into action.