Massachusetts’s First Impeachment

In 1706, the elected political leaders of Massachusetts were at odds with the appointed royal governor, Joseph Dudley.

There were many bones of contention, but Gov. Dudley looked most vulnerable for being in league with wealthy supporters who traded with the French in Canada even during Queen Anne’s War.

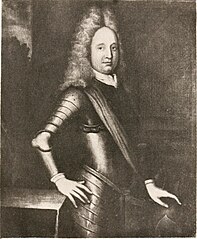

Dudley, a merchant named Samuel Vetch (1668–1732, shown above), and associates used the cover of arranging prisoner exchanges to ship goods, even weapons, to Acadia.

Through a London printer, the Rev. Dr. Cotton Mather published the documents of the case as:

Under the new charter of 1691, however, that legislature’s power was more limited. It no longer chose the governor. It no longer tried cases. But it did have this ill-defined power called “impeachment.”

The legislators decided to use that to get at Gov. Dudley. The lower house would indict his associates, as the House of Commons could, and the upper house, or Council, would try them.

That effort ran into trouble. The charter limited impeachment to a “High Misdemeanor,” not full criminal charges.

Then Chief Justice Samuel Sewall, a member of the Council, advised that the legislature really didn’t have jurisdiction. Sewall might have hoped the case would proceed in his own court, which could treat the behavior as criminal and even impose the death penalty.

Dudley stepped in and urged the Council to proceed anyway with their misdemeanor charge. That upper house found Vetch and his fellow defendants guilty. They weren’t sure what to do next, but eventually a joint legislative committee produced a “bill of punishment” imposing fines and prison time.

Vetch headed to England to argue his case and wield his influence with the imperial government. The privy council ruled the Massachusetts bill invalid, ruling that the General Court had exceeded its authority.

Vetch, having previously run guns to the Acadians, now presented the Crown with a plan to conquer Canada. Then he came back to Massachusetts to lead the invasion. New England Puritans were ready to get behind any plan to attack Catholics, so they went to war behind Vetch in 1710.

As for impeachment, the Massachusetts General Court didn’t try that again until 1774.

TOMORROW: Impeachment resurfaces.

There were many bones of contention, but Gov. Dudley looked most vulnerable for being in league with wealthy supporters who traded with the French in Canada even during Queen Anne’s War.

Dudley, a merchant named Samuel Vetch (1668–1732, shown above), and associates used the cover of arranging prisoner exchanges to ship goods, even weapons, to Acadia.

Through a London printer, the Rev. Dr. Cotton Mather published the documents of the case as:

A memorial of the present deplorable state of New-England, with the many disadvantages it lyes under, by the male-administration of their present governour, Joseph Dudley, Esq. and his son Paul, &c.:Elected politicians made up the lower house of the Massachusetts General Court, or legislature. Under the colony’s original charter, that body really was a court—in fact, it was the highest court in Massachusetts.

Together with several affidavits of people of worth, relating to several of the said governour’s mercenary and illegal proceedings, but particularly his private treacherous correspondence with Her Majesty’s enemies the French and Indians.

To which is added, a faithful, but melancholy account of several barbarities lately committed upon Her Majesty’s subjects, by the said French and Indians, in the east and west parts of New-England.

Under the new charter of 1691, however, that legislature’s power was more limited. It no longer chose the governor. It no longer tried cases. But it did have this ill-defined power called “impeachment.”

The legislators decided to use that to get at Gov. Dudley. The lower house would indict his associates, as the House of Commons could, and the upper house, or Council, would try them.

That effort ran into trouble. The charter limited impeachment to a “High Misdemeanor,” not full criminal charges.

Then Chief Justice Samuel Sewall, a member of the Council, advised that the legislature really didn’t have jurisdiction. Sewall might have hoped the case would proceed in his own court, which could treat the behavior as criminal and even impose the death penalty.

Dudley stepped in and urged the Council to proceed anyway with their misdemeanor charge. That upper house found Vetch and his fellow defendants guilty. They weren’t sure what to do next, but eventually a joint legislative committee produced a “bill of punishment” imposing fines and prison time.

Vetch headed to England to argue his case and wield his influence with the imperial government. The privy council ruled the Massachusetts bill invalid, ruling that the General Court had exceeded its authority.

Vetch, having previously run guns to the Acadians, now presented the Crown with a plan to conquer Canada. Then he came back to Massachusetts to lead the invasion. New England Puritans were ready to get behind any plan to attack Catholics, so they went to war behind Vetch in 1710.

As for impeachment, the Massachusetts General Court didn’t try that again until 1774.

TOMORROW: Impeachment resurfaces.

No comments:

Post a Comment