Boston in 1774 with Notes from Later

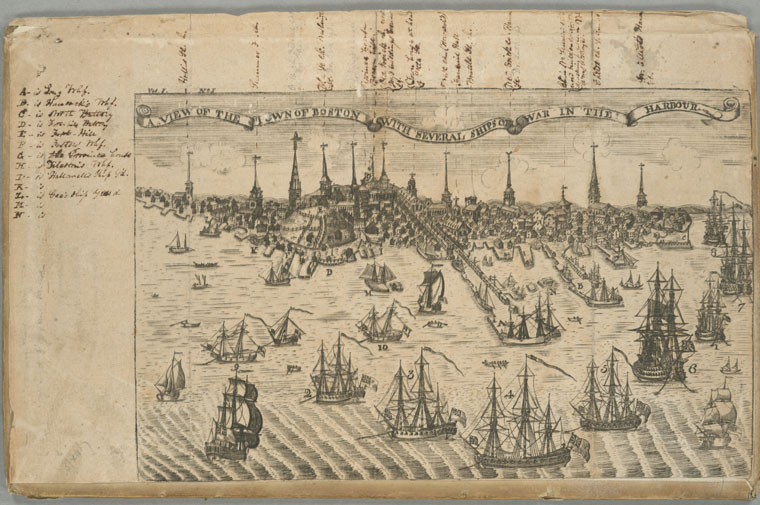

It’s a leaf from Isaiah Thomas’s Royal American Magazine in early 1774 that featured Paul Revere’s engraving of the eastern shore of Boston with Royal Navy ships in the harbor.

This page from the American Antiquarian Society reports that the magazine included a key for this frontispiece inside on page 40. That key identified the labeled landmarks along the water’s edge and the ships. (Though the latter were simply “1,2,3,4,5,6,7 and 8 Ships of War. 9 and 10. armed Schooners.”)

However, this copy of the print was removed from the magazine, and sometime in the early 1800s someone created his or her own key in the margins.

Here’s the handwritten key along the left side; if the key from 1774 said something different, I put that information in brackets:

A- is Long Whf.Originally there was no key for the meetinghouse and church spires dominating the top of the image, but the annotator put a lot of effort into labeling them. And I put a fair amount of effort into reading those labels, including some in pencil that required raising the contrast on those parts of the scan.

B- is Hancock’s Whf.

C- is North Battery

D- is Fort-hill Battery [South Battery]

E- is Fort-Hill

F- is Fosters Whf. [Wheelwright’s Wharf]

G- is the Province house [Beach Hill]

H- is Tilteston’s Whf. [Hubbard’s Wharf]

I- is Hallowell’s Ship Y’d [Hollaway’s Ship-Yard]

K- is [blank] [Walker’s Ship-Yard]

L- is Gee’s Ship Yard [Tyler’s Ship-Yard]

M- is [blank] [Island Wharfs]

N- is [blank] [ditto]

The results are:

Hollis St. Ch.Those labels offer some clues about when the notes were written. The annotator put Old South on “Washington St.,” and that stretch of the street wasn’t officially renamed Washington until 1824. For the Federal Street Church still to be “now Dr. Channings” means that the labels predate 1842. So let’s say around 1830.

Summer St. Ch. [Though was a term for Trinity Church, that building had no steeple; this spire was the New South Meetinghouse on Summer Street.]

First Ch. Federal St.

now Dr. Channings [Rev. William Ellery Channing preached to this congregation from 1803 to 1842; this building was replaced in 1809.]

Old So. Ch. Washington

St. Dr. Eckley’s [Rev. Joseph Eckley’s tenure at Old South ended in 1811.]

Old King’s Chapel

Province house

Beacon light

Old Brick ch. now [?]

Joy’s buildings Cornhill

Sq.

Town house at head

of State St.

West Ch. (Howard’s) [Rev. Simeon Howard died in 1804, and a new church was erected on the site in 1806.]

Faneuil Hall

Brattle St. ch.

New Brick ch. Hanover

St. Dr. Lathrop’s [Rev. John Lathrop died in 1816.]

Ch. in No. Square site

now built over with

dwelling houses. In 1775

it was distroyed. [This was the Old North Meetinghouse.]

Christ Ch. Salem St. [Now best known as Old North Church.]

Dr. Elliot’s Hanover

St. [Rev. Andrew Eliot died in 1778, Rev. John Eliot in 1813.]

It’s a bit confusing that the annotator included the names of some ministers who were dead by that date. I suspect the notes were an attempt to identify who presided over those meetinghouses during the Revolutionary War, at the approximate time of the picture. In the case of Howard, Lathrop, and the older Eliot, they were indeed preaching under those spires in 1774, but Eckley wasn’t installed at Old South until 1780.