“To-morrow I go on another attack”

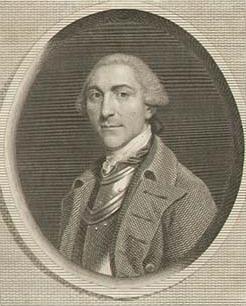

We met Thomas James as a major in the Royal Artillery stationed in New York in 1765. After he vowed to protect the stamped paper and said nasty things about the people opposing the new tax, a crowd attacked his home.

Maj. James went home to Britain to report on the situation to Parliament, and he reported on Parliament to royal authorities in New York.

By 1771 James was a lieutenant colonel in the artillery. In that year he published an illustrated two-volume study titled The History of the Herculean Straits, Now Called the Straits of Gibraltar: Including those Ports of Spain and Barbary that Lie Contiguous Thereto.

The “authour,” as he’s called on the title pages, had served in Gibraltar in 1749–1755. He’d been working on this book for years, and is credited with being the first Englishman to publish observations on the area’s geography.

In 1775 Lt. Col. James was inside besieged Boston. Here’s his brief report on the aftermath of the Bunker Hill battle in a letter to Lt. Col. Francis Downman in London dated 23 June 1775:

We are in thickness of war, we have had two battles already, in the last we carried our point, took the lines and a strong redoubt, with 2,500 men against 7,000.James’s “gondolas” seem to have gone down in American records as the Crown’s “floating batteries.”

We have upwards of 80 officers killed and wounded, and the flower of the grenadiers and light infantry; some regiments have but five grenadiers left. We had at one gun the officer and volunteer wounded, and but one man without a wound. [Capt.-Lt. John] Lemoine is wounded, so are [Capt. W. Oren] Huddlestone and [Lt. Ashton] Shuttleworth. We are well. My volunteer hands have been full.

To-morrow I go on another attack, covering the left in my gondolas, which I have made, viz., three with a heavy 12-pr. in each prow. Adieu.

It’s notable that both sides of the Bunker Hill battle insisted they were heavily outnumbered by the enemy.