On 13 Mar 1806, the

Independent Chronicle of Boston ran this death notice:

Mr. Robert Newman, aged 51. His funeral will be from his late dwelling-house, head of Battery-Wharf, north-end, this afternoon, at 4 o’clock; which the relations and friends are requested to attend.

This was not the same

Robert Newman as the man who hung the lanterns in the

Old North Church on 19 Apr 1775. That Newman’s death notice had appeared in the

Independent Chronicle two years earlier on 28 May 1804:

On Saturday last, Mr. Robert Newman, aged 52—for many years sexton of the North Church. He put a period to his existence with a pistol.

Those two death notices show that there were two men named Robert Newman living in Boston’s North End at the same time. I don’t know if they were related, but they weren’t part of the same household.

Those two Robert Newmans have been thoroughly confused and conflated in local history. So I’m going to try to sort them out.

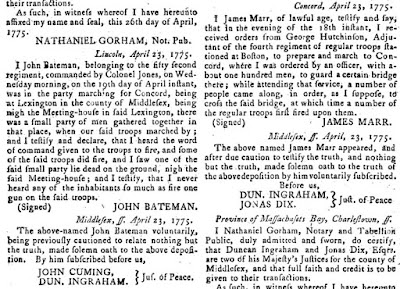

The Robert Newman who died in 1806 was born in or around 1755. He enlisted in Col.

Moses Little’s regiment out of

Ipswich in May 1775, as shown in

Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors of the Revolutionary War. He served a few months that year. He may have also served short stints in 1778 and 1779 and then on the brigantine

Pallas during the Penobscot expedition. This Newman married Esther Treadwell in Ipswich on 22 May 1778.

In September 1779 a group of men petitioned the

Massachusetts Council to commission

this Robert Newman as commander of a

privateer ship: the

Adventure out of

Beverly. The 16 Mar 1780

Independent Chronicle ran a legal notice referring to “Robert Newman, commander of the

armed schooner Adventure.” He turned twenty-five that year.

Robert Newman “at the North End” of Boston was appointed to administer a shipwright’s estate in 1785, according to the 26 September

Boston Gazette. This was probably the mariner. He appears to have made a home in Boston while maintaining his family up on the North Shore.

In July 1790 a child of Robert Newman died in Ipswich of “fits.” On 13 Aug 1797, a four-month-old child of Robert and Esther Newman died in

Newbury. One week later, four children of Robert Newman were baptized in that town at once: Robert, Sally, Thomas, and William.

The 25 Mar 1800

Newburyport Herald reported that “Mrs. Newman, consort, of Capt. Robert Newman,” had died. Newbury vital records confirm her name was Esther, and she was forty-three years old. Six years later the captain himself died in Boston.

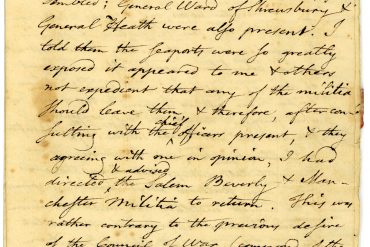

Meanwhile, the other Robert Newman was working as the sexton of Christ Church, better known now as Old North. In addition to

hanging the lanterns in April 1775, he has also appeared on

Boston 1775 charging visitors to see the bodies of British officers killed in the

Battle of Bunker Hill.

In May 1786 the

selectmen of Boston designated twelve men as “Undertakers” and set the prices for burial, tolling a bell, alerting mourners, and “Extraordinary cases, such as putting the bodies into tar’d sheets.” Most if not all those men were sextons, and among them was Robert Newman.

On 14 June 1794 the

Centinel reported that the next day Mrs. Abigail Sumner’s funeral would take place “from the house of Mr. Robert Newman, Salem Street.” That looks like part of his work as an undertaker since I can’t find any family connection.

The sexton had married Rebecca Knox in 1772, but divorced her for having an affair with “one John Skinner.” On 5 Feb 1791 the

Columbian Centinel reported the death of “Mrs. Rebecca Newman, formerly the wife of Mr. Robert Newman, aged 41.” The sexton had already married again, to Mary Hammond, who would bear more of his children and settle his estate. This Robert Newman took his own life in 1804.

TOMORROW: The Freemasonry connection.