Here are answers to the

final questions from the Great 1770 Quiz.

X. Match the following men to their experience of tarring and feathering in 1770.

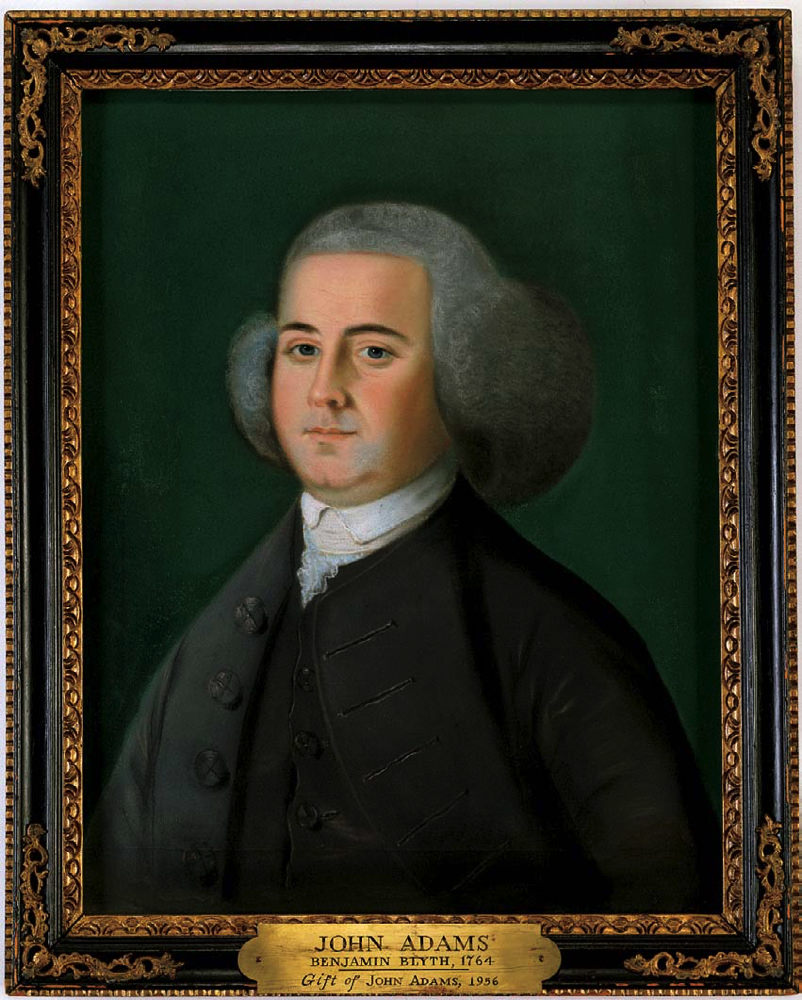

1) John Adams

2) Robert Auchmuty

3) Henry Barnes

4) Theophilus Lillie

5) Patrick McMaster

6) William Molineux

7) Owen Richards

8) Jesse Savil

A) tarred and feathered by a mob in

Gloucester

B) tarred and feathered by a mob led by a

Connecticut captain

C) found his

horse tarred and feathered

D) threatened in writing with tar and feathers while visiting

Salem

E) found the outside of his shop tarred

F) carted around by a

mob with tar and feathers but not tarred and feathered

G) filed

suit against half a dozen people for tarring and feathering someone

H) defended a man accused of tarring and feathering someone

I discussed

George Gailer’s lawsuit against the people who attacked him with tar and feathers in October 1769

back here.

Robert Auchmuty was his lawyer (thus G) while

John Adams defended

David Bradlee (thus H).

Ben Irvin’s 2003

New England Quarterly article “Tar, Feathers, and the Enemies of American Liberties, 1768-1776” lists all the other incidents in its appendix. Other historians mention them as well.

Owen Richards and

Jesse Savil were low-level

Customs officers.

Henry Barnes,

Theophilus Lillie, and

Patrick McMaster were businessmen who defied the

non-importation movement.

The threat to tar and feather

William Molineux was an anomaly. Instead of enforcing the Customs laws or defying non-importation, he defied Customs laws and enforced non-importation. But that threat is recorded on the front page of the 20 Aug 1770

Boston Gazette,

as shown here, right under a mention of tar and feathers being readied for importers in Woodbridge, New Jersey. By the

sestercentennial of that news item, I hope to understand it a little better.

The correct answers are thus Adams (H), Auchmuty (G), Barnes (C), Lillie (E), McMaster (F), Molineux (D), Richards (B), and Savil (A). Once again, both

Kathy and

John got all the answers right.

XI. One of the most famous men in the British Empire visited Massachusetts in August and September 1770 and never left. Who was he?

This question offers so few specifics that I don’t think it’s Googlable. It’s a test of knowledge of the British Empire in 1770 and Massachusetts trivia.

The man was the Rev.

George Whitefield. The popular British

evangelist made many preaching tours through America. According to his

1877 biography and the

1903 edition of

John Rowe’s diary, Whitefield’s final New England tour saw him preaching at:

- Rhode Island: Newport (4-8 Aug), Providence (9-12 Aug).

- Massachusetts: Attleboro (13 Aug), Wrentham (14 Aug), Boston at various churches (15-18 Aug), Malden (19 Aug), Boston again (20-24 Aug), Medford (26 Aug), Charlestown (27 Aug), Cambridge (28 Aug), Boston again (29-30 Aug), Jamaica Plain in Roxbury (31 Aug), Milton (1 Sept), Roxbury again (2 Sept), Boston again (3 Sept), Salem (5 Sept), Marblehead (6 Sept), Salem again (7 Sept), Cape Ann (8 Sept), Ipswich (9 Sept), Newburyport (10-11 Sept), Rowley (12-13 Sept), [laid low by diarrhea, 14-16 Sept], Boston again (17-19 Sept), Newton (20 Sept), [ill again, 21-22 Sept].

- New Hampshire: Portsmouth (23-25 Sept).

- Maine: Kittery (26 Sept), York (27 Sept).

- New Hampshire: Portsmouth again (28 Sept), Exeter (29 Sept).

Whitefield returned to Newburyport, but he died at 6:00 A.M. on 30 September. Per his wish, the minister was

buried in the crypt of the Newburyport meetinghouse, shown above.

Both

John and

Kathy answered this question correctly.

XII. Young servant Charles Bourgate accused his master Edward Manwaring, a Customs official, of shooting at the crowd during the Boston Massacre. At Manwaring’s trial in December, however, a jailhouse informant testified to hearing Bourgate say that Elizabeth Waldron had induced him to tell that lie. What did Waldron allegedly offer Bourgate for his testimony?

This question helpfully pointed to a specific moment of testimony, but of course the challenge is finding a record of that moment. A report on

Edward Manwaring’s trial was

printed alongside the transcript of the

Rex v. Wemms et al. trial of the

soldiers for the

Boston Massacre—but not in every copy.

The copy of the trial record that

Harbottle Dorr must have bought early and bound with his newspapers

ends with an index of witnesses. But later copies like this one on archive.org

have an appendix reporting on Manwaring’s acquittal.

I’ll discuss

Charles Bourgate’s accusations next month. For now, I’ll just quote what a debtor named

James Penny testified that the

French boy had told him:

That what he testified to the Grand Jury and before the Justices…was in every particular false, and that he did swear in that manner by the persuasion of William Molineux, who told him he would take him from his master and provide for him, and that Mr. Molineux frightened him by telling him if he refused to swear against his master and Mr. Munro the mob in Boston would kill him: and farther that Mrs. Waldron, the wife of Mr. Waldron a taylor in Back-street, who sells ginger bread and drams, gave him the said Charles gingerbread and cheese, and desired him to swear against his master.

The answer to this question is thus “gingerbread and cheese.”

And it’s further evidence that William Molineux was

everywhere in 1770 Boston.

Once again,

Kathy and

John both knew the putative bribe.

XIII. Three brothers from Massachusetts, two of them prominent in one of 1770’s most famous events, are said to have died at the same place, yet they were thousands of miles apart. Who were they, and how is this possible?

One of 1770’s most famous events was the Boston Massacre trial, and reports of that proceeding often note that

Samuel Quincy (1735-1789) was one of the prosecutors while his younger brother

Josiah Quincy, Jr. (1744-1775), was one of the defense attorneys.

Did they have a third brother? Yes, Edmund Quincy (1733-1768), who was a merchant rather than a lawyer.

And where did the three men die? They all died “at sea,” but in different corners of the north Atlantic. Edmund was on a voyage to the

Caribbean for his health. Josiah was returning to Massachusetts after meeting with British Whigs in the crucial winter of 1774-75. And Samuel, having become a

Loyalist and taken a Customs service job in Antigua, was sailing to Britain with his second wife, again in hopes of restoring his health, and died off the African coast.

The Quincy brothers’ deaths was the tricky bit of trivia that got me thinking about making another quiz. I’m pleased that fact wasn’t too obscure for people to find. Or at least not too obscure for both

John and

Kathy.

By the narrow margin of a single question,

John provided the most correct answers. Congratulations to him, to

Kathy for an impressive performance, and to everyone else who puzzled over this quiz.

(John, please comment on this posting with your mailing address, which I’ll keep private, and I’ll send you a copy of

The Atlas of Boston History provided by the University Press of Chicago.)