As related in

yesterday’s posting, a storm in September 1767 pushed a

schooner packed with

whale oil onto

Cape Cod.

But that ship wasn’t lost, the cargo was preserved, and nobody died. Not much drama after all.

Nonetheless, the stories of two survivors—evidently

Nantucketers Stephen Hussey and

Richard Coffin—contained enough emotion to inspire

John Wheatley’s

enslaved teen-aged servant

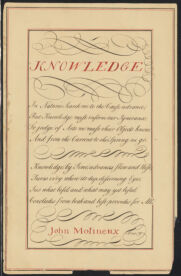

Phillis to write 24 lines of poetry (plus a prose interlude).

Titled “On Messrs. Hussey and Coffin,” that poem appeared in

Samuel Hall’s

Newport Mercury on 21 Dec 1767—the first recognized publication by Phillis Wheatley.

You can read the lines here alongside Amelia Yeager’s essay about the publication for the Newport Historical Society.

David Waldstreicher starts his new study of the poet,

The Odyssey of Phillis Wheatley, with this poem and returns to it often as a touchstone of her work, particularly for her braiding of classical and Calvinist motifs and her ocean imagery.

The poem and its publication raise some small questions beyond the identity of the two men,

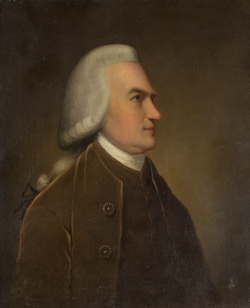

discussed yesterday. One is why Hussey’s name appears first in the poem’s title and in the anecdote published with it in the newspaper even though Coffin was the ship’s captain and the only person named in the reports of the grounding.

I suspect this was a matter of personality. Hussey seems to have been a sociable man, connecting the Boston and Nantucket business communities before the war; serving in Whig political gatherings; speaking for Nantucket businessmen to both the British and Patriot governments during the war (islanders wanted to stay neutral for both economic and religious reasons); and eventually taking a post with the federal

Customs bureau. I suspect he just told the story better.

Another question is whether Phillis Wheatley and the family who owned her sought this publication. I think the answer to that is clear in how the poem appeared in the

Boston Post-Boy when that newspaper reprinted it on 11 Jan 1768. The “Wheatley” name was eliminated:

-

“belonging to one Mr. Wheatley of Boston” became “belonging to a Gentelman [sic] of Boston”

-

“being at Mr. Wheatley’s, and, while at Dinner” became “being at Dinner”

-

The name at the bottom of the poem changed from “Phillis Wheatley” to simply “PHILLIS.”

Obviously

printers John Green and Joseph Russell thought the Wheatleys didn’t want their surname linked to the poem. They may even have heard directly from the family. However supportive of their protégée and property the Wheatleys became later, at the start of 1768 they were still reticent about what we’d call publicity.

I suspect that’s why this poem didn’t appear in a Boston newspaper until after it could be credited as “From the

Newport Mercury.” John Wheatley was a wealthy merchant who occasionally advertised, the sort of gentleman local newspaper printers would want to keep happy.

Still, someone must have circulated the poem privately in manuscript for it to get from Boston to Newport. That might have been the Wheatleys, sharing the news among friends and expecting it to stay private. Conversely, the poem might have been spread by Hussey and Coffin within their

Quaker network. (I doubt the teen poet had developed her own out-of-town network yet.)

I tested a couple of other possible explanations for the first publication in

Rhode Island:

-

Did the Newport Mercury run poetry while the Boston papers weren’t yet in that habit? No, Boston printers shared a lot of poems in the 1760s.

-

Was Capt. Coffin’s near-shipwreck bigger news in Rhode Island than in Boston since it involved a Nantucket ship? Not only is Nantucket closer to Newport, but both places had large Quaker communities. However, Samuel Hall didn’t pick up the Boston reports about the schooner grounding. (The Providence Gazette for 10 October did carry the second item, reporting Coffin’s ship was safe.*)

In the end, I think someone in Newport who didn’t know the Wheatleys learned about the poem and the story behind it, and asked the local printer to publish it. Hall in turn was beyond John Wheatley’s reach.

What would have prompted such a Newporter to send to poem to Hall? That person was clearly struck by how the author was “a Negro Girl,” and enslaved at that. That’s not merely a footnote to the poem; it’s in the preface, the implicit reason for printing it.

Even the name “Phillis Wheatley” at the bottom of the poem might be significant. Many other early publications credited the poet only by her first name. For example,

Ezekiel Russell’s broadside of her elegy to the Rev.

George Whitefield said: “By PHILLIS, a Servant Girl of 17 Years of Age, Belonging to Mr. J. WHEATLEY, of Boston.” By 1770 the Wheatley family had become comfortable having their names attached to such publications, but the prevailing style was still not to formally acknowledge enslaved people’s surnames.

Those details make me think whoever asked Hall to print the poem wanted readers of the

Newport Mercury to know an enslaved girl had written it—and perhaps to see that that girl was an individual. And, though nothing about the presentation commented on the injustice of slavery, was it possible to avoid that thought?

(* In the database that I access through Genealogy Bank, the 10 October and 3 October

Providence Gazettes are mushed together. Looks like something went wrong when they were photographed for microfilm.)