“Lifetime Tenure” When the Supreme Court Began

Social-media discussions of this issue got me thinking of what a “lifetime appointment” meant when the U.S. Supreme Court first met.

Lifetime judicial appointments were common in the British and thus British-American legal systems. Although overall life expectancy was lower in the eighteenth century, that’s largely due to childhood mortality, so once a mature man was appointed to the bench he often served for many years.

(Colonial Rhode Island was an exception to that system of lifetime appointments. Under its eighteenth-century constitution, judges were elected for one-year terms, though they could be reelected. Which just shows how anomalous Rhode Island was.)

I decided to look at the Supreme Court justices appointed in the 1790s to see how long they stayed alive and stayed on the court.

- John Jay / 6 years on the court / 40 more years of life after appointment

- John Rutledge / 1 one year on the court, then another stint of a few months four years later / 11 more years of life

- William Cushing / 20 / 20

- James Wilson / 9 / 9

- John Blair / 5 / 10

- James Iredell / 9 / 9

- Thomas Johnson / 2 / 28

- William Paterson / 13 / 13

- Samuel Chase / 15 / 15

- Oliver Ellsworth / 4 / 11

- Bushrod Washington / 31 / 31

That said, while the first generation of U.S. politicians could conceive of Supreme Court justices serving for decades, the number of jurists who actually do so has gone up. As of today the historical average tenure on the court stands at sixteen years, but no justice has left the bench before that time since the late 1960s.

The other career model we see these days, a justice serving for decades and then retiring, was less common in the 1790s. Indeed, the three early justices who resigned citing reasons of health—John Blair, Thomas Johnson, and Oliver Ellsworth—did so after only a handful of years. The job was more physically demanding when Supreme Court justices still rode the circuit to hear federal cases rather than staying in the capital.

One path we haven’t seen for a long time was a justice resigning from the top bench because he preferred a different government role. John Jay left the court to be governor of New York, having already run for that offce in 1792 and gone overseas as President George Washington’s treaty negotiator in 1794.

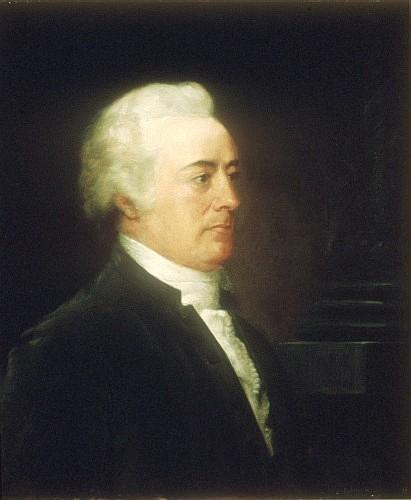

Finally, there’s a storyline we really don’t want to see repeated. John Rutledge (shown above) resigned from the U.S. bench to become chief justice in the home state of South Carolina. Then President George Washington put him back on the Supreme Court as chief justice, only for the senate to decline to confirm him. Rutledge attempted suicide, withdrew from public life, and died five years later.

.jpg)