“Terror Twice Told” Seminar in Boston, 3 Apr.

The reading for the seminar is Boston University professor Brendan McConville’s paper “Terror Twice Told: Popular Conventions, Political Violence, and the Coming of the Constitutional Crisis, 1780-1787.” The event description says:

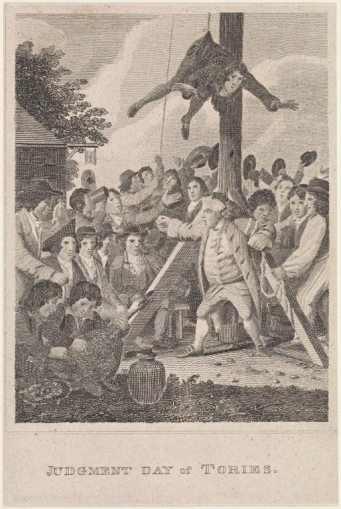

As the revolutionary war ended, members of committees, conventions and other extraordinary revolutionary institutions continued to operate as independent political actors. Between 1781 and at least 1786, committeemen and conventioneers launched forceful, violent efforts to reengineer American society. Committee-directed mobs expelled “tories” from many communities, and committeemen and conventioneers used both local laws and contract theory to legitimate these expulsions.The main commentary will be offered by University of Connecticut professor Richard D. Brown. Then discussion can become general.

This paper argues that the wave of political violence after the American victory at Yorktown in 1781 ultimately reflected conflicts within the American political community over who could be an American, what institutions constituted “the people” in a republic, and the character and limits of the “the people’s” power to form self-governing institutions. These disputes played an important role in creating the 1787 constitutional crisis.

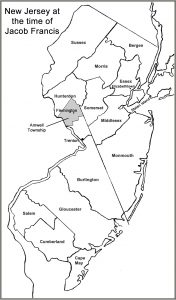

McConville is the author of The King’s Three Faces: The Rise and Fall of Royal America, 1688-1776 and These Daring Disturbers of the Public Peace: The Struggle for Property and Power in Early New Jersey.

Brown is the author of numerous books including Self-Evident Truths: Contesting Equal Rights from the Revolution to the Civil War, Taming Lust: Crimes Against Nature in the Early Republic (coauthored by Doron S. Ben-Atar), The Hanging of Ephraim Wheeler: A Story of Rape, Incest, and Justice in Early America (coauthored by Irene Quenzler Brown), The Strength of a People: The Idea of an Informed Citizenry in America, 1650-1870, Knowledge Is Power: The Diffusion of Information in Early America, 1700-1865, and Revolutionary Politics in Massachusetts: The Boston Committee of Correspondence and the Towns, 1772-1774.

This seminar is scheduled to start at 5:15 P.M. It is free and open to the public, but the society asks people to R.S.V.P. to ensure seating and adequate munchies for afterward. In addition, the conversation will be much easier to follow if one comes early to peruse the paper.