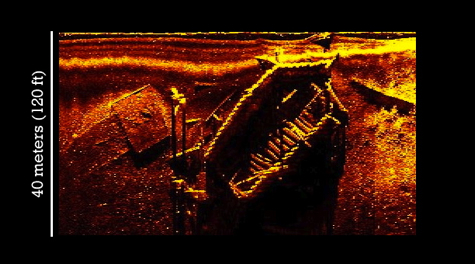

In mid-1776, when he was elected to the Continental Congress, Judge Richard Stockton was living on his estate in Princeton, New Jersey, which his poetically inclined wife Annis had named Morven. The picture above shows the mansion at the center of that land. In the eighteenth century its wings were only one storey tall, and those classical porches are undoubtedly additions as well, but it was still a big, handsome house.

In mid-1776, when he was elected to the Continental Congress, Judge Richard Stockton was living on his estate in Princeton, New Jersey, which his poetically inclined wife Annis had named Morven. The picture above shows the mansion at the center of that land. In the eighteenth century its wings were only one storey tall, and those classical porches are undoubtedly additions as well, but it was still a big, handsome house.

I’ve been discussing Stockton’s experience after being captured by Loyalists in late 1776. What happened to his house? The British army was marching down through New Jersey that fall. On 29 November, the Ten Crucial Days timeline says, Princeton College closed and Stockton left town. According to his entry in the Biography of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence, he moved “his wife and younger children“ into another county. Elizabeth Ellet’s profile of Annis Stockton in The Women of the American Revolution says, “His eldest son, Richard, then a boy twelve years of age, with an old family servant, remained in the house.” The “servant,” according to modern historians, was probably enslaved. This genealogy webpage lists Richard’s siblings, including some older sisters.

The American army retreated through Princeton in the first week of December, and the British arrived on the 7th. A week later, Gen. William Howe ordered his British and Hessian troops to go into winter quarters where they were. According to Washington’s Crossing, by David H. Fischer, a group of dragoons (mounted infantry) took over Morven. Presumably young Richard had rejoined his mother and siblings by this point, but that’s not clear.

Gen. George Washington led the American forces in a surprise counterattack at Trenton on 25-26 Dec 1776, changing the military situation in southern New Jersey. Gen. Cornwallis arrived at Morven late on the night of 1-2 Jan 1777 and slept a few hours there—just long enough that it gets remembered as “Cornwallis’s headquarters.” There was another battle at Trenton, and on 3 January the two armies met at the Battle of Princeton. The British lost and moved to New Brunswick, eventually leaving most of the state.

The Stocktons apparently returned home to Morven in January, finding widespread damage. The earliest source on damage there that I’ve found is a letter from the couple’s son-in-law, Dr. Benjamin Rush, stating that the judge had been “plundered of all his household furniture and stock by the British army.” However, before the Battle of Princeton some Americans had heard rumors of Stockton swearing loyalty to the king. Might some of the looting have been done by resentful Continental troops?

In any event, the damage to Morven became a big part of the Stockton family’s memory of the war. In speaking to historians, they emphasized how much property the judge had lost. The Biography of the Signers, written in the early 1820s, stated:

His fortune, which had been ample, was greatly diminished, both by the depreciation of the continental currency, and the wanton depredations of the British army. His papers and library, one of the best possessed by any private citizen at that period, were burned; his domestic animals, (particularly his fine stock of horses,) and almost all his personal property, were plundered or destroyed, and his farm laid waste.

Mr. Stockton now found himself the proprietor of a little more than his devastated lands, and was compelled to have recourse to the temporary aid of some of his friends, whose losses had been less extensive, for a present supply of such articles of necessity as were essential to relieve the pressure of absolute suffering.

Ellet’s history, published in 1840, adds more detail:

The house was pillaged, the horses and stock were driven away, and the estate was laid waste. The furniture was converted into fire-wood; the old wine, stored in the cellar, was drunk up, and the valuable library, with all the papers of Mr. Stockton, committed to the flames. The house became for some time the headquarters of the British general.

The [silver] plate and other valuable articles belonging to the family had been packed in three boxes and buried in the woods, at some distance from the mansion. Through treachery—it is said—the place of concealment was discovered by the soldiers, and two of the boxes were disinterred and rifled of their rich contents. The remaining one escaped their search and was restored to the family. The daughter of Mrs. Stockton residing in Princeton, has in her possession several pieces of silver that were in this box, and are now, of course, highly valued.

She has also two portraits—one of Mr. Stockton and the other of his wife, which were in the house when occupied by the British, and found among some rubbish after their departure. Both were pierced through with bayonets. Some years since, they were entirely restored by the modern process, and now occupy their honored place in Mrs. Field’s house. The portrait of Mr. Stockton is a very fine one, and understood to have been painted by [John Singleton] Copley.

Those descriptions are no doubt the basis of modern statements about Stockton’s financial suffering—but those statements go even further. For instance, in 2000

Boston Globe columnist Jeff Jacoby wrote, “His family lived on charity for the rest of their lives.” (Yes, I found a

copy of his essay online.) The

Morven Institute of Freedom, which is named for Stockton’s estate but has no connection to it, states that Stockton

died a pauper as the British had destroyed and burned most of his wealth. It only was after the war that his family regained the land where stood the home that had been lost by their father.

His

UShistory.org biography says:

He lost all of his extensive library, writings, and all of his property during the British invasion. He died a pauper in Princeton at the age of 51 [actually 50].

None of those essays acknowledge Stockton’s oath of loyalty to the Crown. Instead, they stretch the sources to build up the legend of him as a martyr for American independence.

Stockton’s descendants didn’t describe long-lasting poverty. The

Biography reported that Stockton needed “temporary aid” from friends immediately after his return, not that he lived on their charity for the next four years. Some of the books that say all of Stockton’s papers were burned also go on to quote from his letters. If Stockton suffered from the “depreciation of the continental currency” later in the war, that means he must have accumulated some of that currency along the way. Primary sources indicate that at the end of April 1777 Stockton was

shopping for new furniture.

Furthermore, later Stocktons were just as proud to show off the nice things they had inherited from their Revolutionary ancestors as to imply that those ancestors had been wiped out by the nasty British. About that furniture? Thomas Allen Glenn wrote in

Some Colonial Mansions and Those Who Lived in Them that in 1899 Maj. Samuel Witham Stockton of Princeton owned “Many rare old pieces of mahogany furniture, relics of Colonial Morven,...together with many of the family portraits.” So either some furniture from “Colonial Morven” was

not burned, or the family had enough money after Stockton’s imprisonment to buy mahogany. (As for those portraits, they’re not by Copley; in the mid-1800s, practically every eighteenth-century American portrait got labeled as a Copley.)

All in all, it seems clear that there was looting and damage at Morven in December 1776 and January 1777, with books stolen or burned and the dragoons taking away all the good horses. But the Stockton family was rich, with lots of land and connections, so they had a financial cushion under them. They continued to enjoy an upper-class life.

The younger Richard Stockton graduated from Princeton College on 29 Sept 1779, delivering the English oration “on the principles of true heroism.” When the judge died in 1781, young Richard inherited Morven—which wouldn’t have been possible if the estate were tied up in debts. (The Morven Institute’s statement that the family reacquired the land must be based on trying to reconcile a belief that Judge Stockton lost everything with the fact that the family continued to live on that estate for two more generations.)

Morven was in such good shape that widow Annis Stockton hosted Gen. Washington there on 28 Aug 1781 and several times in 1783. She reportedly served dinner on “china, which is of the dark-blue willow-ware pattern” and remained in the family for at least another century.

And the mansion’s still there, as the photograph above shows. Morven served as the official residence of the state’s governors from 1945 to 1981, and is now “a museum and public garden showcasing the cultural heritage of New Jersey.”

COMING UP:

Summing up Richard Stockton’s story.