“A concert hall is again opened to all”

But on 6 Feb 1769, the Whig-leaning Boston Gazette and Boston Evening-Post ran this advertisement:

The Subscribers to the Concert,So the biweekly musical assemblies were back on, with just a two-day delay that week.

which was to have been on Wednesday Evening the 8th Instant, are hereby notified that it will be on Friday the 10th, at Concert-Hall; and after that will be continued every other Wednesday, during the Season.

In their “Journal of Occurrences,” the Boston Whigs tried to spin the resumption of concerts in their favor on 16 February:

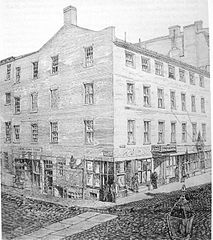

A concert hall is again opened to all who have, or may commence subscribers to such musical entertainments. We are told proper concessions have been made Mr. [Stephen] D[e]bl[oi]s, and that G[eneral] [John] P[omero]y, has engaged that the o—ff[ice]rs of his core, shall for the future behave with decency, and agreeable to the regulations of such assemblies.And there was no further commotion. On 29 May, the Boston Chronicle announced:

The Subscribers to the Wednesday-Night CONCERT, are hereby notified, that said Concert will end, Wednesday next.The season thus passed without giving the Whigs anything further to complain about.

N.B. Any Gentlemen who are not Subscribers and Ladies, will be admitted to said Concert, at Concert-Hall, paying half a Dollar each.

The Concert begins at half after Seven.

No Subscribers will be admitted without delivering his Ticket.

Concert Hall wasn’t the only venue offering musical entertainment that winter, and I’m not talking about James Joan’s “Music Hall.” On 17 February the Whigs ran another dispatch:

There has been within these few days a great many severe whippings; among the number chastised, was one of the negro drummers, who received 100 lashes, in part of 150, he was sentenced to receive at a Court Martial,—It is said this fellow had adventur’d to beat time at a concert of music, given at the Manufactory-House.The drummers of the 29th were black, bought or recruited in the Caribbean. At first Bostonians had viewed them as a curiosity, then as a threat to the regular social order since drummers were tasked with carrying out the whippings and other corporal punishments in a regiment. But here, when a drummer was receiving punishment, the Whigs were mildly sympathetic to him.

It’s unclear why a regimental drummer would be punished for playing at a concert. Soldiers were allowed to earn money by taking jobs in their off-hours, and other sources show regimental musicians giving private concerts. Indeed, it’s possible that much of the band at the subscription concerts had come from the army. Perhaps this drummer played the concert when he was supposed to be on duty, or had been expressly told not to play at the Manufactory given its recent history as a battleground between army and locals. The Whigs might have neglected to include such a detail.

This news item is another odd link, after Pvt. William Clarke’s play The Miser, between the Manufactory building or its tenants the Browns and popular entertainment. Perhaps as immigrants the Browns just didn’t share Boston’s traditional resistance to such public frivolities. But any “concert of music” at the Manufactory was probably meant for a lower-class audience than the assemblies at Concert Hall.