Capt. Dobel at Home and on the Far Side of the World

Except for several months as a Continental Navy lieutenant under Capt. John Manley, which ended badly, Joseph Dobel appears to have spent the Revolutionary War ashore in Boston. Certainly when he was in charge of confining suspected enemies of the state he was at home.

After peace came, Dobel resumed work as a merchant captain, commanding a three-masted ship called the Commerce in 1789. Newspapers indicate he made regular trips to Liverpool and also sailed to Cadiz, Spain.

In December 1790, Dobel’s first wife, Mary, died at age fifty-five. I haven’t found mention of any children from this marriage. A little less than three months later, Capt. Dobel married “Mrs. Susanna Joy,” who was about forty years old.

In the early 1790s, the Boston town meeting started to elect Capt. Dobel as a culler of fish (or dry fish). That was one of several minor offices tasked with making sure that particular goods sold in town met quality standards. Dobel’s election shows what his neighbors felt he was expert in. With his colleagues he periodically advertised in the newspapers warning against unofficial fish-culling.

In 1793 Capt. Dobel was living “in Bennet-Street, opposite the North-School.” Early in that year he dissolved a business partnership with Thomas Jackson. I can’t find any earlier advertisements from this firm, so I have no idea what they dealt in.

In those years, American merchants and captains were seeking new business outside the British Empire—beginning the new nation’s “China Trade” and “East India Trade.” One distant destination was the island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean, then called “Isle-of-France.” In March 1792, after a full year away from Boston, Capt. John Cathcart brought in the Three Brothers from Mauritius “with a cargo of Sugars” for the merchant Thomas Russell. In May 1795 the Massachusetts Mercury ran a report that Cathcart was back at Mauritius.

Cathcart returned to Massachusetts again that year and oversaw the construction of a new ship, the Three Sisters, in Charlestown. It was about 340 tons burden, “Copper Bolted and sheathed.” Soon he took it out on its maiden voyage to Asia.

And then in May 1796 the Boston newspapers reported that Capt. Cathcart had died “two days sail from St. Jago”—Santiago, the largest island in the country of Cape Verde. The merchants who invested in that cruise and the families of all the crew must have worried about what would happen next. But all they could do was collect snatches of news brought back by other ships’ captains.

As of August, the first report to reach the newspapers said, the Three Sisters was at Mauritius, its next stop uncertain. Claypoole’s American Daily Advertiser stated that in February 1797 it was at Bengal. In May the Boston Price-Current said that the ship was at Manila. By this time the principal investor, Russell, had died.

I mention all that because Joseph Dobel had signed on as Cathcart’s next-in-command. He had the responsibility of completing the voyage. Most of those dispatches listed Cathcart as the Three Sisters’ captain, adding that he was dead, while a couple gave Dobel’s name. Meanwhile, the ship was still lingering on the far side of the world. The Massachusetts Mercury reported that “The Three Sisters, Doble, of Boston, sailed from Calcutta for N. York Sept. 19 [1797], sprung a leak, and returned.”

It wasn’t until that spring of 1798 that the Three Sisters was back in the north Atlantic. In late March there were two reports of it being spotted in or near Delaware Bay. Finally, on 27 June, Capt. Dobel brought the ship into New York harbor. That was more than two years after the news that Cathcart had died.

On 31 July a notice in the New-York Gazette announced that the Three Sisters “will be sold reasonable, with all her stores as she came from Calcutta, and the terms of payment made convenient.” Another advertisement, noting that the ship was built “under the superintendence of the late Capt. JOHN CATHCART,” appeared in Russell’s Gazette in Boston the next month.

Those ads promised that the Three Sisters was “a remarkable fast sailer” and only two and a half years old. But the expense of the extraordinarily long voyage meant the ship’s owners needed cash fast.

TOMORROW: Capt. Dobel and the U.S.S. Constitution.

After peace came, Dobel resumed work as a merchant captain, commanding a three-masted ship called the Commerce in 1789. Newspapers indicate he made regular trips to Liverpool and also sailed to Cadiz, Spain.

In December 1790, Dobel’s first wife, Mary, died at age fifty-five. I haven’t found mention of any children from this marriage. A little less than three months later, Capt. Dobel married “Mrs. Susanna Joy,” who was about forty years old.

In the early 1790s, the Boston town meeting started to elect Capt. Dobel as a culler of fish (or dry fish). That was one of several minor offices tasked with making sure that particular goods sold in town met quality standards. Dobel’s election shows what his neighbors felt he was expert in. With his colleagues he periodically advertised in the newspapers warning against unofficial fish-culling.

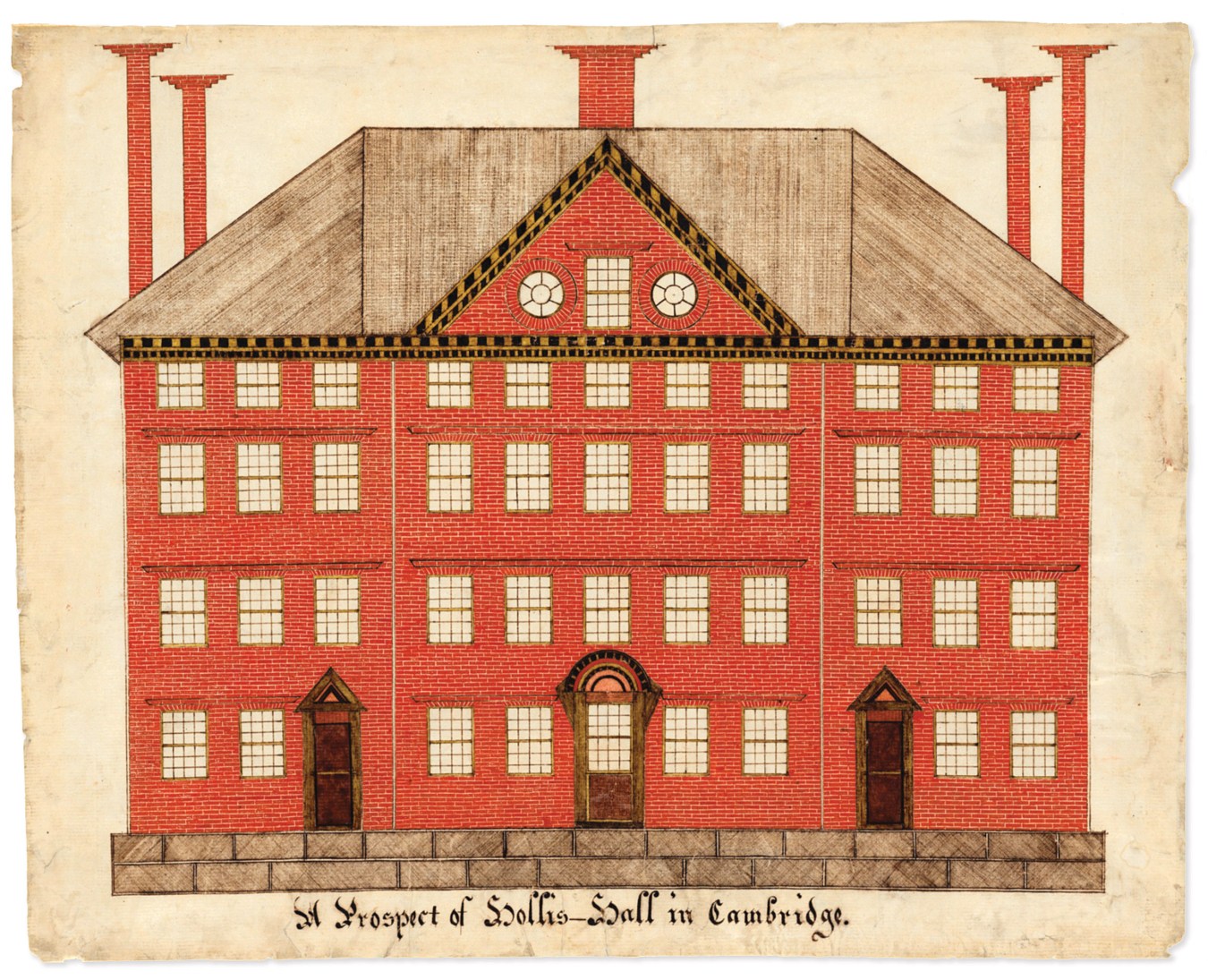

In 1793 Capt. Dobel was living “in Bennet-Street, opposite the North-School.” Early in that year he dissolved a business partnership with Thomas Jackson. I can’t find any earlier advertisements from this firm, so I have no idea what they dealt in.

In those years, American merchants and captains were seeking new business outside the British Empire—beginning the new nation’s “China Trade” and “East India Trade.” One distant destination was the island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean, then called “Isle-of-France.” In March 1792, after a full year away from Boston, Capt. John Cathcart brought in the Three Brothers from Mauritius “with a cargo of Sugars” for the merchant Thomas Russell. In May 1795 the Massachusetts Mercury ran a report that Cathcart was back at Mauritius.

Cathcart returned to Massachusetts again that year and oversaw the construction of a new ship, the Three Sisters, in Charlestown. It was about 340 tons burden, “Copper Bolted and sheathed.” Soon he took it out on its maiden voyage to Asia.

And then in May 1796 the Boston newspapers reported that Capt. Cathcart had died “two days sail from St. Jago”—Santiago, the largest island in the country of Cape Verde. The merchants who invested in that cruise and the families of all the crew must have worried about what would happen next. But all they could do was collect snatches of news brought back by other ships’ captains.

As of August, the first report to reach the newspapers said, the Three Sisters was at Mauritius, its next stop uncertain. Claypoole’s American Daily Advertiser stated that in February 1797 it was at Bengal. In May the Boston Price-Current said that the ship was at Manila. By this time the principal investor, Russell, had died.

I mention all that because Joseph Dobel had signed on as Cathcart’s next-in-command. He had the responsibility of completing the voyage. Most of those dispatches listed Cathcart as the Three Sisters’ captain, adding that he was dead, while a couple gave Dobel’s name. Meanwhile, the ship was still lingering on the far side of the world. The Massachusetts Mercury reported that “The Three Sisters, Doble, of Boston, sailed from Calcutta for N. York Sept. 19 [1797], sprung a leak, and returned.”

It wasn’t until that spring of 1798 that the Three Sisters was back in the north Atlantic. In late March there were two reports of it being spotted in or near Delaware Bay. Finally, on 27 June, Capt. Dobel brought the ship into New York harbor. That was more than two years after the news that Cathcart had died.

On 31 July a notice in the New-York Gazette announced that the Three Sisters “will be sold reasonable, with all her stores as she came from Calcutta, and the terms of payment made convenient.” Another advertisement, noting that the ship was built “under the superintendence of the late Capt. JOHN CATHCART,” appeared in Russell’s Gazette in Boston the next month.

Those ads promised that the Three Sisters was “a remarkable fast sailer” and only two and a half years old. But the expense of the extraordinarily long voyage meant the ship’s owners needed cash fast.

TOMORROW: Capt. Dobel and the U.S.S. Constitution.