Alarming News from Across the Atlantic

On Monday the 18th, Capt. James Hall had arrived from England with copies of the London Public Advertiser describing how the imperial capital had reacted to receiving news of the Boston Massacre back on 5 March.

The first word had reached London on 22 April. The next day, the Earl of Hillsborough, Secretary of State for North America, summoned Sir Francis Bernard, still officially the royal governor of Massachusetts, for consultation.

That evening the London newspapers published the Boston Gazette’s account of the killing, a statement from the Boston town meeting, and a letter from the Whigs to former governor Thomas Pownall. All of those sources of course blamed the royal authorities.

On 23 April, a Sunday night, there was a “Cabinet Council” about the news. The next day, Lord Hillsborough met with colonial governors and agents in a “grand levée at his house.” Those meetings gave rise to several rumors about what the government might do next: appoint Sir Jeffery Amherst commander-in-chief in North America, send more troops to Boston, repeal the tea tax before resigning? The tea tax was the last of the Townshend duties, and ending it would have been a total victory for the non-importation movement. (None of those things happened.)

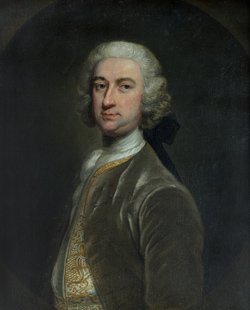

Parliament met on 26 April. Member Barlow Trecothick, also a London alderman with close links to the Boston business community, formally asked the ministry to share all communications about Boston. Reportedly Hillsborough and Lord North had promised him a formal vote would not be necessary, but he “did not chuse to trust their assurances.” The ensuing debate included Edmund Burke, Isaac Barré, George Grenville, and others. It ended with agreement that the government would share the information with names redacted.

As part of that discussion, the London newspapers (still dashing out most names because it wasn’t clearly legal yet to report parliamentary debates) quoted Viscount Barrington, Secretary of War, as saying that Boston magistrates didn’t support the troops, and:

That the Government is a Democracy, and all civil Officers chosen by the People,—that the Council is a democratical Part of that Democracy,—that in his Opinion a Royal Council is necessary for a more proper Division of Powers of Government.Such a Council appointed in London would be part of the Massachusetts Government Act of 1774.

Then on 28 April more documents arrived from Boston. Some were in the same vein as before. A letter from Lt. Col. William Dalrymple reportedly said Bostonians “had absolutely DETERMINED to risk their lives in an Attack upon the Military; in order to revenge the cruel and wanton Massacre of their Countrymen”—which is not what that army colonel would have ever written.

But the bombshell printed in the 28 April Public Advertiser, and reprinted in the 21 June Boston News-Letter after it went back across the Atlantic, was the “Case of Capt. Thomas Preston of the 29th Regiment.” This 2,000-word account of the Massacre started with complaints of Bostonians being mean the soldiers, proceeded through a detailed account of the shooting on King Street that blamed the violent crowd, and concluded with warnings of the slanted local press. (The London newspapers, and thus the News-Letter, omitted Preston’s final paragraphs asking for a pardon.)

The Boston Whigs were upset because back in March Preston had sent the Boston Gazette a short letter thanking the town and praising its justice system. Even as he did so, those politicians realized, the captain must have been preparing this very different message for Customs Commissioner John Robinson to carry to London.

TOMORROW: The anger of the people.