The Sites of the Sheffield Resolves

Wikipedia’s entry also says that document was written “in the Colonel John Ashley House, a registered National Historic Landmark in Ashley Falls, a neighborhood of Sheffield, Massachusetts.”

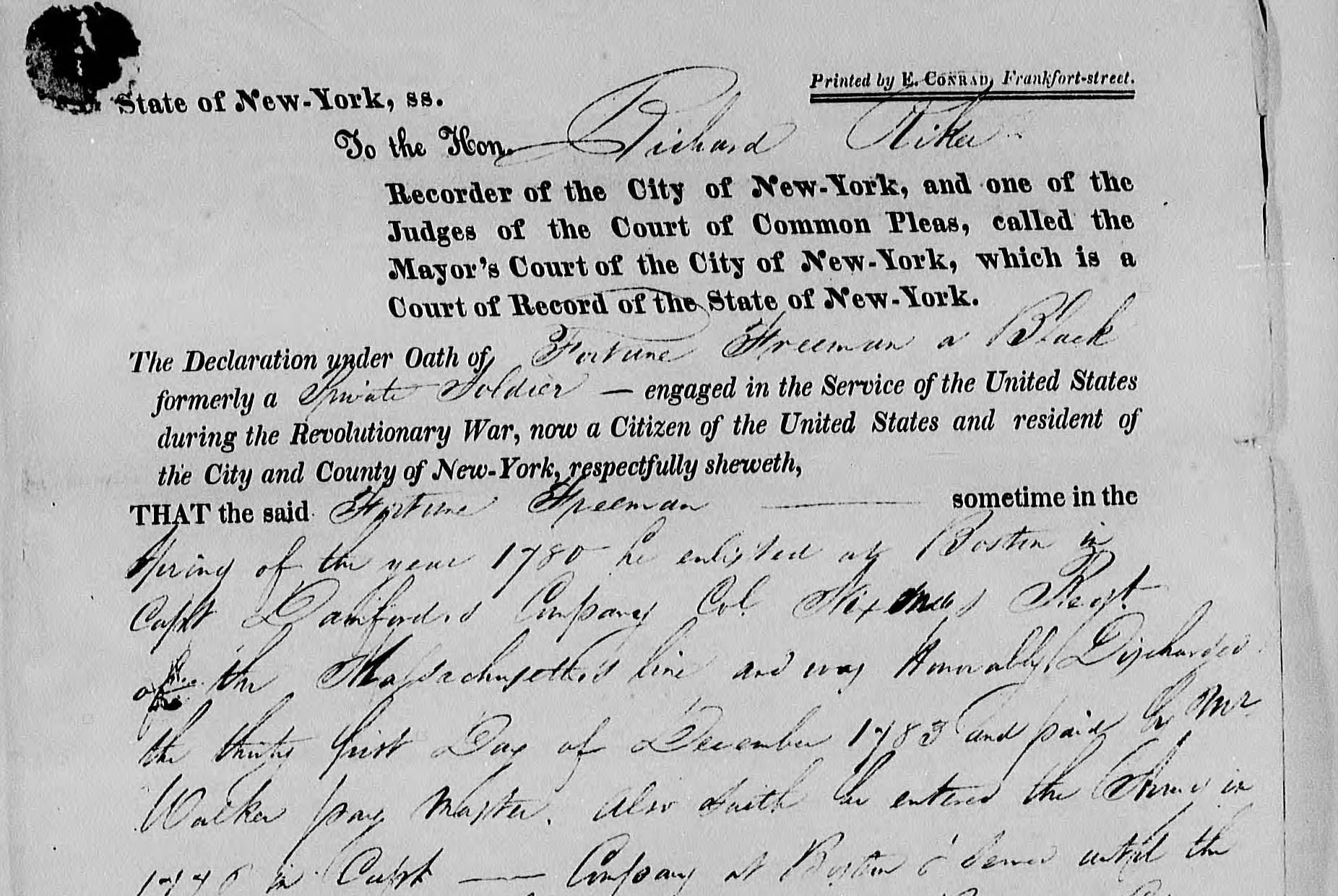

The Ashley House, built in 1735 and moved in 1930, has been owned for the last half-century by the Trustees of Reservations. Its own website now emphasizes the paradox of John Ashley owning slaves while signing onto natural-rights rhetoric, and Elizabeth Freeman’s enslavement in the house.

The link between the Sheffield resolves and the Ashley house is actually quite thin, apparently based on the idea that Ashley was “moderator” of the committee to draft the resolutions.

When Boston newspapers reported that Ashley had been “chosen moderator,” that meant he moderated the 5 January town meeting that appointed the committee, not that he was moderator of the committee. He was just one of eleven men named to that subgroup.

Committees had chairmen, not moderators, and the chairman was almost always the first man named in the record—in this case, young attorney Theodore Sedgewick. Towns often appointed a lawyer, schoolteacher, or other educated man to head such committees when they wanted some fancy words.

Sedgewick probably drafted the resolutions at his own home, which still stands in Sheffield but has been greatly modified. It also appears to be in private hands, thus not open to tourists.

The town committee probably met to go over Sedgewick’s draft in advance of the follow-up town meeting—whether a couple of days before or one hour before we don’t know. Did the committee meet at Ashley’s house? It’s possible, depending on whether that house was conveniently located and people liked the colonel’s hospitality. If he had a tavern license, the odds go up. But there’s nothing in the historical record to say the committee met there, much less that most of the drafting was done there.

Sheffield held its town meetings in its religious meetinghouse. That church still stands as well, moved back from the road and with a steeple added in 1819, and still has an active congregation. In that building the town formally adopted the resolves with a unanimous vote. That vote gave Sedgewick’s words official standing.

Nonetheless, the “Sheffield Declaration” gets associated with the Ashley House.

Historic houses benefit from having stories attached to them, preferably stories carrying emotional and historical weight. Stories benefit from having concrete settings, especially those people can visit. Thus, there’s a natural gravitation of stories to sites.

TOMORROW: A new statue in Sheffield.